Remembering an Eastern Orthodox Prophet: Nicholas Berdyaev, by Bradley J. Birzer

One kind of weird but enticing academic puzzle for me is discovering and delving into the works of interesting figures of the 20th century who have been largely forgotten. And, by “interesting figures,” I mean especially those who espoused types of religious humanism and their allies.

TIC mastermind Winston Elliott feels the same way, and one of the purposes of founding TIC was to bring the memory of these humanists back to the public and honor each as a vital ancestor to our own broad cause in the twenty-first century.

Everyone remembers, for example, G.K. Chesterton, T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and, more recently, Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy. Even if one hasn’t read any of their respective works, their names circulate with familiarity even in the darker corners of American civilization.

At a different, slightly lower level hover Irving Babbitt, Hilaire Belloc, Paul Elmer More, Willa Cather, Christopher Dawson, Jacques Maritain, Etienne Gilson, Josef Pieper, Walter Miller, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, and Russell Kirk.

But only a very few remember eccentrics such as T.E. Hulme, Aurel Kolnai, Leo Ward, Sister Madeleva Wolff, Wilhelm Roepke, Romano Guardini, Gabriel Marcel, Owen Barfield, Theodore Haecker, David Jones, Tom Burns, and Bernard Wall.

Nicholas Berdyaev (1874-1948), a member of this last group, has been sadly neglected as well, at least by those in conservative and libertarian circles.

He was, not surprisingly, connected to many Christian Humanists of his day. He knew the Maritains well, and while C.S. Lewis mostly dismissed his work as a sideline show, Christopher Dawson considered Berdyaev’s thought central to the restoration of the 20th-century West.

The trump card, here, though is from a fellow Russian. A figure no less important or heroic than Alexandr Solzhenitsyn discussed Berdyaev briefly in volumes II and III of The Gulag. He was, Solzhenitsyn wrote, offering perhaps the highest praise possible, “a man.”

In volume II, he described Berdyaev as the ultimate person to reject Soviet terror.

So what is the answer? How can you stand your ground when you are weak and sensitive to pain, when people you love are still alive, when you are unprepared? What do you need to make you stronger than the interrogator and the whole trap? From the moment you go to prison you must put your cozy past firmly behind you. As the very threshold, you must say to your self: ‘My life is over, a little early to be sure, but there’s nothing to be done about it. I shall never return to freedom. I am condemned to die–now or a little later. But later on, in truth, it will be even harder, and so the sooner the better. I no longer have any property whatsoever. For me those I love have died, and for them I have died. From today on, my body is useless and alien to me. Only my spirit and my conscience remain precious and important to me.’ Confronted by such a prisoner, the interrogation will tremble. Only the man who has renounced everything can win that victory. But how can one turn one’s body to stone? Well, they managed to turn some individuals from the Berdyayev [sic] circle into puppets for a trial, but they didn’t succeed with Berdyayev. They wanted to drag him into an open trial; they arrested him twice; and (in 1922) he was subjected to a a night interrogation by Dzerzhinsky himself. Kamenev was there too (which means that he, too, was not averse to using the Cheka in ideological conflict). But Berdyayev did not humiliate himself. He did not beg or plead. He set forth firmly those religious and moral principles which had led him to refuse to accepted the political authority established in Russia. And not only did they come to the conclusion that he would be useless for a trial, but they liberated him. A human being has a point of view!”

In volume 3 of The Gulag, Solzhenitsyn wrote simply: Berdyaev was a “philosopher, essayist, brilliant defender of human freedom against ideology.”

Exiled from Russia in 1922 after surviving three Soviet trials against him, Berdyaev settled in Paris, living there until his death in 1948.

While in Paris, Berdyaev became an integral part of the Jacques and Raissa Maritain circle. Indeed, as Berdyaev remembers it in his fine autobiography, Dream and Reality, he and Jacques served as equal poles in the creation and perpetuation of the group. Though Maritain’s extreme Thomism struck Berdyaev as a form of Catholic ideology, he respected the French philosopher immensely. He did joke, however, that Maritain’s fear and rejection of Protestantism and Protestants was a strange element of the convert, implying a certain irrationality.

When Christopher Dawson and Tom Burns first formed the Order group in Chelsea, London, employing the resources of the publishing house Sheed and Ward to unify all humanists of British and Europe backgrounds, Dawson immediately sought out Maritain and Berdyaev. Each contributed to one of the best book series of the last century, the 16 volume Essays in Order. As it turned out, Essays in Order served as the one attempt in the twentieth century to bring all Christian Humanists together into a unified Republic of Letters.

When Essays in Order folded, Dawson continued the same project with a second friend, Bernard Wall, publishing a journal, Colosseum. Again, Dawson and Wall sought out and received the contributions and acclaim of Berdyaev and Maritain.

One of Berdyaev’s most interesting books–and presumably the reason Dawson thought so highly him–was his The End of Our Time, written between 1919 and 1923 and published for the first time in English in 1933 by Sheed and Ward. In almost every way, though clearly a Russian and a member of the Eastern Orthodox faith, Berdyaev anticipated the major arguments of the English-Welsh Roman Catholic Dawson.

In particular, Berdyaev stressed the primacy of culture and theological issues over politics and economics as truer forms of reality. Almost the entire western world, Berdyaev argued, had embraced some form of materialism after the collapse of Christendom. And, this moved the world rapidly toward unreality.

“We must begin to make our Christianity effectively real,” Berdyaev wrote, “by a return to the life of the spirit.” Economic matters, he continued, “must be subordinated to that which is spiritual, [and] politics must be again confined confined within their proper limits.”

read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

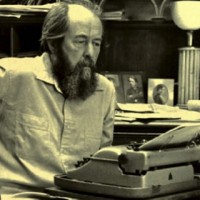

Solzhenitsyn: The Courage to be a Christian, by Joseph Pearce.

In these dark days in which the power of secular fundamentalism appears to be on the rise and in which religious freedom seems to be imperiled, it is easy for Christians to become despondent. The clouds of radical relativism seem to obscure the light of objective truth and it can be difficult to discern any silver lining to help us illumine the future with hope.

In such gloomy times the example of the martyrs can be encouraging. Those who laid down their lives for Christ and His Church in worse times than ours are beacons of light, dispelling the darkness with their baptism of blood. “Upon such sacrifices,” King Lear tells his soon to be martyred daughter Cordelia, “The gods themselves throw incense.”

It is said that the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church and, if this is so, more bloody seed has been sown in the past century than in any of the bloody centuries that preceded it. Tens of millions have been slaughtered on the blood-soaked altars of national and international socialism in Europe, China, Cambodia and elsewhere. Today, in many parts of the world, millions upon millions are being slaughtered in the womb in the name of “reproductive rights.”

In such a meretricious age the giant figure of Alexander Solzhenitsyn emerges as a colossus of courage. Born in Russia in 1918, only months after the secular fundamentalists had swept to power in the Bolshevik Revolution, Solzhenitsyn was brainwashed by a state education system which taught him that socialism was just and that religion was the enemy of the people. Like most of his school friends, he enslaved himself to the zeitgeist, became an atheist and joined the communist party.

Serving in the Soviet army on the Eastern Front during the Second World War he witnessed cold blooded murder and the raping of women and children as the Red Army took its “revenge” on the Germans. Disillusioned, he committed the indiscretion of criticizing the Soviet leader Josef Stalin and was imprisoned for eight years as a political dissident.

While in prison, he resolved to expose the horrors of the Soviet system. Shortly after his release, during a period of compulsory exile in Kazakhstan, he was diagnosed with a malignant cancer in its advanced stages and was not expected to live. In the face of what appeared to be impending death, he converted to Christianity and was astonished by what he considered to be a miraculous recovery.

Throughout the 1960s Solzhenitsyn published three novels exposing the secularist tyranny of the Soviet Union and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. Following the publication in 1973 of his seminal work, The Gulag Archipelago, an exposé of the treatment of political dissidents in the Soviet prison system, he was arrested and expelled from the Soviet Union, thereafter living the life of an exile in Switzerland and the United States. He finally returned to Russia in 1994, after the collapse of the Soviet system.

In 1978, Solzhenitsyn caused great controversy when he criticized the secularism and hedonism of the West in his famous commencement address at Harvard University. Condemning the nations of the so-called free West for being morally bankrupt, he urged that it was time “to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.”

Read the complete article in Crisis Magazine

Eric Hobsbawm, 1917-2012, by Roger Kimball

In the annals of moral idiocy, the Marxist British historian Eric Hobsbawm, who died yesterday at 95, will ever enjoy a conspicuous place. A gifted and prolific writer, the Egyptian-born Hobsbawm was utterly absorbed by the ideology that fired his youthful dreams of utopia. How he must have savored the fact that he was born in 1917, the year of the Bolshevist revolution in Russia which ushered in so much poverty, misery, terror, and freedom-blighting totalitarian oppression. “The dream of the October Revolution is still there somewhere inside me,” Hobsbawm wrote in his memoir Interesting Times in 2002, “I have abandoned, nay, rejected it, but it has not been obliterated. To this day, I notice myself treating the memory and tradition of the USSR with an indulgence and tenderness.”

Indeed. Hobsbawm was adulated by an academic establishment inured to celebrating partisans of totalitarian regimes so long as they are identifiably left-wing totalitarian regimes. Although he claimed to have been victim of a “weaker McCarthyism” that retard advancement of leftists in the UK, Hobsbawm enjoyed a stellar career replete with official honors, preferments, and perquisites. He was showered with honors and academic appointments at home and abroad. His books won all manner of awards. In 1998 he was appointed to the Order of the Companions of Honor. But the central fact about Hobsbawm, as about so many doctrinaire leftists, was his willingness to barter real people for imaginary social progress. If he “abandoned, nay rejected” the “dream” of the October Revolution, he never abandoned its animating core: an almost reflexive willingness to sacrifice innocent lives for the sake of a spurious ideal.

The philosopher David Stove once identified “bloodthirstyness” as the motivating force of Communism and its offshoots. Scratch a socialist and you discover a fondness for the gulag. This describes Hobsbawm to a T. In 1994, the venerable historian discussed the former Soviet Union with a television interviewer. What Hobsbawm’s position comes down to, the interviewer suggested, “is saying that had the radiant tomorrow actually been created, the loss of fifteen, twenty million people might have been justified?” Hobsbawm: “Yes.”