Tintin: The True European, by Peter Strzelecki Rieth

As Europe struggles with economic woes brought on by the combination of unrestricted government largess and corruption and avarice, it seems every thread of this current struggle emanates from the problem of European character and the concurrent angst surrounding it. A brief reflection on the problem of European character and an illustration of how centered it is at the causal crux of the European crisis may equip us to provide some solutions.

In brief, what I call the problem of European character and the concurrent angst surrounding it is the fact that the essence of the European Union, the modern European political project, is a negation of war between European nations. This means that the European character, if one can even speak of such a thing, is founded in the proposition that whatever happens, Europeans must remain united, for division inevitably leads to a war of all against all and the annihilation of European civilization. The founding event of this outlook was World War II. As such, there is no positive defining trait of European character, only a negation of war, which is to say that modern Europe is founded on the fear of being toward death. This special kind of glue holding the Union together is, to my mind, best defined using Heidegger’s concept of angst. Thus, when crisis strikes on account of numerous errors, a fear sets in against tampering with the ailing union as that may lead to its collapse and to war. Yet to do nothing, or as some quarters are urging, to strengthen the faulty bonds of union even further, will lead also to collapse and war because it will deepen the crisis and give rise to public aggravation and revolutionary fervor. The diagnosis is clear: the European Union, which arose from the common European character trait of angst, cannot sustain itself by angst. The European character must be enriched with positive traits or be undone.

Some “Euro-enthusiasts” may well now shake their heads and claim that this expanded, positive European character already exists, made visible in the thousands of pages of regulations instructing the citizenry on how to be tolerant, open-minded humanitarians who love mother Earth, their fellow man, and embrace science. The chief problem with this view, abstracting from the philosophical questions that arise regarding the desirability of this particular modern, ahistorical, and secular European character, is that it resides in regulations, not in the heart of the people. Regulation lacks the personal import even of law. The importance of this distinction is such that regulation dictates the minutiae of everyday life. It not only prescribes an ethos, as law does, it dictates the precise, quantified application of said ethos. Civilizations which are built on virtues, whether piety or tolerance, that are mandated, registered, stamped, and stipulated in paragraph 16, subsection 2 of the revised revision of the regulations revising previous revisions–such civilizations die.

Here, angst will worry: does it therefore follow that Europeans are destined to fall back on national and ethnic prejudices? Perhaps there are other alternatives available to them besides secular, liberal sophistication masking bureaucratic banality or some pompous nationalist stereotypes. Certainly the philosophers present us with numerous alternatives, though all of them might well be impractical for any landmass not populated by a majority of philosophers. We also cannot, it appears to me, reach far back into European history, for to expect of modern Europeans to adopt Roman virtue, Athenian wisdom, let alone Christian agape, may well be expecting too much. If we wish to look for something in modern European history grounded in a firmer basis than philosophical speculation then I suggest we look no further than Tintin.

Tintin, for those who do not know and love him, is the European par excellence, created by author Hergé. His authority is widely acknowledged by children throughout the world, regardless of their age. General DeGaulle apparently called Tintin his only international rival. Tintin, if one really thinks about it, is the perfect template for a European character rooted in positive traits rather than merely in angst. Rather menacingly, the present generation risks knowing Tintin not through his European manifestation, but through the rather poor interpretation of his adventures presented to the world by the American director Steven Spielberg. All the more reason why I shall now endeavor to make a composite defense of Tintin as being of paramount importance and relevance to the present crisis.

First, Tintin has proven himself a keen political realist. I begin with this because some may well now expect me to embark on platitudes regarding Boy Scout virtues as exemplified by Tintin, rather than say anything of hard-nosed relevance to the grave situation Europe faces. Quite the contrary! It was Tintin, who, back in 1929, exposed the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union and the plight of its people at a time when the vast majority of Western opinion was either ignorant of or fascinated with the Soviet system. Tintin’s revelations were, for decades, characterized as childish caricatures until the publication of the Black Book of Communism made the broad public aware of what Tintin had reported as fact from the very outset. This, if nothing else, qualifies Tintin for serious consideration as a relevant voice in European affairs: where so many were wrong about the Soviet Union, he was right from the beginning.

Detractors will no doubt point out that Tintin may well have been stunningly right in his premiere journalism, but quickly followed up on that by being stunningly wrong in his treatment of European colonialism. From his wholesale slaughter of the helpless species populating the Congo, to his insensitive remarks to a room full of Congolese regarding their homeland “Belgium”, one quickly can see why these detractors may feel it quite a bad idea to hold Tintin up as a worthy ideal for European character. Why, at one point, Tintin even helped a Priest!

Yet the measure of ideals is not their perfection, but rather how they deal with their all too human imperfections. In the case of young Tintin in Congo, he did what he could to help the native populations, while everything we might be tempted to fault him for was, as author Hergé admitted, the result of not taking his work too seriously at the time and being unreflective about the prejudices of his age. Out of all of Tintin’s remarkable adventures, his sojourn through the Congo may be most fraught with vices, but we can take heart that Tintin learned from his mistakes, as we can see in his escapades in the Far East shortly after leaving the Congo. There, Tintin so exemplified courageous virtues in his gallant struggle to aid the Chinese in their time of desperation as to have earned the praise of Chiang Kai-Shek himself, not to mention endearing himself to the Dalai Lama, who to this day declares his love for the boy reporter.

This evolution from a rhino-hunting, crocodile-dynamiting, Al Capone-chasing adventurer into a serious young man of high moral principle and gallant instinct betrays a character trait sorely lacking in the modern European. The modern European is nihilistic in private, bureaucratic in public. Tintin, by contrast, demonstrated a a playful lightness and joi de vivre in his private life combined with moral conscience in public life. Tintin’s youth, his evolution, is not linear, but rather curvilinear. In the beginning, he fluctuates between noble deeds like helping the Indians by fighting exploitative Americans and lighthearted slap stick. Yet as Tintin’s experience of the world grows, his moral imagination is refined and his humor matures. The latter is actually tied intimately with the former, as moral reflection is quite impossible without humor. Only a character type like that of Tintin’s could permit such an evolution, and only a European of such character could hope to escape the trap of modern European Union: the prospect of despotic union or war, both laced with angst.

Tintin’s political teaching does not, however, stop there. He provides us with a wonderful illustration of the folly of radical factionalism and demonstrates how it is always the mother of despotism. How memorable his misadventures are in the banana republic of Generals Alcazar and Tapioca, where revolutions take place on a daily basis, where the people oscillate between wild revolutionary fervor and grinding tyranny, where no matter who wins, dictatorship and poverty remain constant. The illustration, although set in a South American context, certainly does tell us quite a bit about human nature and the folly of revolutions. Far from being a means towards salvation from tyranny, Tintin seems to teach us that strife, faction, and partisan division are a direct route to tyranny. Civilized people, in contrast to the banana republics, Tintin suggests, never engage in revolution but rather rely on other means. Revolutions appear an easy solution, but end up solving nothing while expending the accumulated public stock of disappointed hope.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

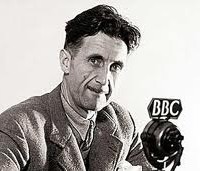

George Orwell’s Despair, by Russell Kirk.

In the twentieth century, no novelist exerted a stronger influence upon political opinion, in Britain and America, than did George Orwell. Also Orwell was the most telling writer about poverty. In a strange and desperate way, Orwell was a lover of the permanent things. Yet because he could discern no source of abiding justice and love in the universe, Orwell found this life of ours not worth living. In his sardonic fashion, nevertheless, he struck some fierce blows at abnormality in politics and literature.

“There is no such thing as genuinely nonpolitical literature,” Orwell wrote in his essay on “The Prevention of Literature” (1945), “and least of all in an age like our own, when fears, hatreds, and loyalties of a directly political kind are near to the surface of everyone’s consciousness….It follows that the atmosphere of totalitarianism is deadly to any kind of prose writer, though a poet, at any rate a lyric poet, might possibly find it breathable. And in any totalitarian society that survives for more than a couple of generations, it is probable that prose literature, of the kind that has existed during the past four hundred years, must actually come to an end.” Soviet Russia supplies the proof: “It is true that literary prostitutes like Ilya Ehrenberg or Alexei Tolstoy are paid huge sums of money, but the only thing which is of any value to the writer as such—his freedom of expression—is taken away from him.”

read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

“Non c’è successo economico senza ordine morale”, by Maria Claudia Ferragni

In questa prima settimana di luglio, nel corso della quale gli americani festeggiano l’anniversario della loro indipendenza, si trovano in Italia due economisti legati alla presidenza Reagan: Howard Segermark, ex-collaboratore di Arthur Laffer, l’economista che ha impostato teoricamente la Reaganomics, e Grover Norquist, fondatore e Presidente di Americans for Tax Reform, considerato uno degli uomini più influenti di Washington (oggi parlerà in un incontro pubblico a Roma alle 17 presso l’Hotel Nazionale, in piazza Montecitorio). Entrambi ospiti del Columbia Institute, portano in Italia la loro esperienza di indomiti paladini della libertà economica e individuale. Ma ci raccontano anche di un’America che sta vivendo un momento storico di transizione e che si sta avviando sempre più in fretta verso la pericolosa strada dello stato sociale europeo, anche per ciò che riguarda la messa in discussione dei valori fondanti la civiltà occidentale.

Della attuali sfide della galassia conservatrice abbiamo parlato a Milano con Howard Segermark, oggi vice presidente della Patten Associates, società specializzata in relazioni con il governo, esperto lobbista a difesa dei diritti di proprietà, attivo in molteplici associazioni e fondazioni conservatrici anche in ambito culturale.

Signor Segermark, qual è la situazione attuale del movimento conservatore negli Stati Uniti?

I Conservatori si trovano ad affrontare i problemi creati dalle politiche del presidente Obama. In particolare, il suo risultato più importante nel corso del primo mandato è stata l’approvazione dell’Obamacare (la nuova legge che rende obbligatoria l’assicurazione sanitaria per tutti, ndr), una vera e propria usurpazione massiccia dell’assistenza medica da parte dello stato. E’ ora chiaro che la legge approvata dal Congresso non potrà essere applicata a partire dall’anno prossimo, come era stato promesso, e non potrà essere implementata senza un massiccio incremento delle tasse. Inoltre, circa il 25% degli americani resterà ancora privo di un’assistenza sanitaria adeguata. Quindi la legge non ha risolto il problema per il quale è stata creata, sarà molto più costosa del previsto e, infine, probabilmente ridurrà l’ambito dell’assistenza medica per gli americani. Ciò accade perché non è mai successo che i burocrati siano in grado di risolvere un problema. Il Senatore repubblicano Paul Ryan (candidato alla Vice-Presidenza lo scorso novembre, ndr) ha invece una proposta alternativa, che restituisce alla persona la libertà e responsabilità di decidere quale piano di assistenza sanitaria scegliere e mi auguro che possa essere approvata se nel 2016 dovesse essere eletto Presidente un repubblicano. L’Obamacare, invece, impone ai giovani pesanti carichi fiscali per sostenere le spese sanitarie degli anziani; mentre sarebbe meglio, come previsto da Ryan, creare incentivi perché i giovani possano risparmiare per pagarsi da soli l’assistenza medica quando saranno a loro volta anziani.

Quali sono altri problemi che i conservatori devono affrontare?

La grande recessione economica. Da quando Obama è stato eletto, gli Stati Uniti hanno avuto una crescita inferiore al 3% in ciascun quadrimestre, senza soluzione di continuità. Di conseguenza, l’America ha vissuto una diminuzione di ricchezza a cui non era abituata, al contrario dell’Europa che sembra essersi assuefatta a questi dati statistici. Le politiche di Obama hanno sottratto circa 2.800 miliardi di dollari all’economia e non possiamo non pensare a quale tragedia sia questa perdita di ricchezza in termini di posti di lavoro, investimenti, ricerca. Quando l’economia vive un periodo di stagnazione, in Europa le persone si rivolgono allo Stato, che in un certo senso acquisisce nuovi “clienti”: ecco, questa situazione per noi americani è nuova, ma siamo arrivati al punto che ci sono oggi 70 milioni di americani che vivono con i “food stamps”(buoni pasto statali, ndr), ma è un sistema molto corrotto perché ormai da molti anni i food stamps vengono venduti sul mercato nero a 50 centesimi l’uno per ogni dollaro di valore. Ad esempio, una famiglia di 4 persone che ha 100 dollari in buoni pasto può ottenerne 50 vendendoli al mercato nero, per comprare la birra… E’ quindi un sistema che per il 50% si risolve in uno spreco totale.

Osservandoli dall’esterno, sembra che i Conservatori non riescano a trovare la strada giusta o il candidato giusto per risollevarsi, è vero?

Vede, tutta la politica americana negli ultimi vent’anni si è trovata ad affrontare due grandi problematiche: la caduta del Muro di Berlino e l’11 settembre. Nessuno dei due partiti è unanime nel modo di risolvere questi problemi. Obama ha ridicolmente vietato l’uso della parola “terrorismo”, definendo ad esempio l’attacco di chiara e lampante matrice jihadista nella base militare di Fort Hood del 2009 “un’atto di violenza sul posto di lavoro”… Si tratta perciò davvero di una situazione politica complessa e anche i Democratici hanno difficoltà nel digerire questo tipo di interpretazione dei fatti. Inoltre, nel mondo di oggi in cui gli Stati Uniti sono l’unica vera super-potenza globale è molto difficile gestire la politica estera: bisogna forse smettere di pensare di intervenire in ogni singolo conflitto nel mondo? L’esempio della Siria è emblematico: mi chiedo se gli Stati Uniti hanno un interesso diretto in quel conflitto. L’unico che ha mai sostenuto la politica americana è Assad… certo, è un dittatore. Ma se gli Stati Uniti consentono ai jihadisti e ai cloni della Fratellanza Musulmana di conquistare un altro Paese, questo non aiuterà il conflitto né la causa della civiltà occidentale.

Come ha reagito l’opposizione repubblicana?

Ecco, si tratta di uno degli esempi migliori della spaccatura che stanno vivendo. Il senatore John McCain è andato in Siria e ha incontrato molte persone chiedendo di creare una “no fly zone” sulla Siria, che corrisponde a un atto di guerra, mentre Obama sta cercando di armare alcuni dei ribelli, ma non sa bene chi siano e, di fatto, non lo sa nessuno. E’ indubbio allora che pensare di intervenire per creare una democrazia, come non siamo riusciti a fare in Iraq e in Afghanistan, diventerebbe un atto di hubris politica.

Read the complete article in La Nuova Bussola Quotidiana