Posted on Jan 29th, 2013 in

Academy,

History,

West |

0 comments

Christopher Dawson wrote with two different audiences in mind. He sought both to displace the bankrupt Victorian and Edwardian liberalism of his own day and to shake the complacency of his coreligionists who preferred to bask in the quickly fading light of false medievalism. His carefully crafted prose revealed a nuanced and original understanding of Western history.

To combat “scientific” theories of progress, Dawson argued that every civilization relies on those who most fully represent its ideals and shape the culture through their actions. Dawson maintained that “history is at once aristocratic and revolutionary. It allows the whole world situation to be suddenly transformed by the action of a single individual.” It is this dynamic historical process that is fatal to a secular understanding of religious approaches to history. In the words of Edmund Burke that Dawson quoted with approval, at times a “common soldier, a child, a girl at the door of an inn have changed the face of the future and almost of Nature.” To the Christian, this understanding of historical development permits interpretation of past events in the light of divine will and spiritual forces that may be unknown even to the actors themselves.

Dawson set out for himself the task of explaining the twofold nature of Christian history: while the Christian faith embodies eternal values and the teachings of God, it nevertheless transforms utterly the cultures it contacts. When the Christian faith enters into a culture, as when it first burst upon an overcivilized and jaded Rome, it begins a spiritual regeneration that affects not only the material, external culture, but the interior constitution of its members. In an essay entitled “The Christian View of History,” Dawson wrote:

For the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation is not simply a theophany—a revelation of God to Man; it is a new creation—the introduction of a new spiritual principle which gradually leavens and transforms human nature into something new. The history of the human race hinges on this unique divine event which gives meaning to the whole historical process.

This new, world-transforming history overthrows its rivals, whether the Greek idea of an endless series of repeating cycles or the spiritless homogeneity of the “postmodern” era. The Incarnation gives shape to history and supplies a beginning, a middle, and an end: “the Christian view of history is a vision of history sub specie aeternitatis, an interpretation of time in terms of eternity and of human events in the light of divine revelation.” This concentration on the physical substance of the Christian faith was a conscious counterweight to overly aesthetic theories of Christianity, such as the “super-Christianity” of Matthew Arnold, for example, which reduced the force of religious belief to a set of humanistic nostrums.

The figures whom Dawson chose to study highlight his interest in the transformative power of the Christian faith: St. Augustine, who formed Christian thought out of the ruins of the old world order; St. Thomas Aquinas, whose reception of the Greek-Arabic body of scientific knowledge created a new movement in Western thinking without compromising its integrity; and St. Ignatius Loyola, who inaugurated a new spirituality to confront the challenges of the Reformation. Dawson saw the present age as one similar to that of Augustine or Ignatius, and in need of saints who have the vision to lead the faithful into the next era. The Western world, he thought, was facing another of its “cultural discontinuities” that displace the old order and usher in a new social reality. The question that remained, for Dawson as for Eliot, was whether this new era was to be Christian or a “new civilization which recognizes neither moral laws nor human rights.”

Dawson wished first to reassert the importance of a millennium of Christian belief to modern history. It is not necessary to be a Christian to recognize that Christianity has played a profound role in shaping European culture and that “there is no aspect of European life which has not been profoundly affected” by that faith. Dawson sought to counter the skeptics of his day who saw in Christianity at best a series of moral tales (and at worst mere pretexts) that had no lasting influence on Western social practice or political arrangements. This aspect of his writings won him many admirers, including T. S. Eliot and Arnold Toynbee.

Posted on Jan 28th, 2013 in

France,

History |

0 comments

If a thing is worth doing at all, it’s worth doing badly…

This paradoxical witticism of Chesterton was on my mind as I sat down to watch The War of the Vendée, a recent film about the forgotten martyrs of the French Revolution. I was pleased that a film had been made to honour the heroes of the Vendée but I feared that it would be a really bad film. Certainly everything seemed to suggest that it would be awful. It was made with a miniscule budget and a cast of dozens as opposed to thousands. How could a couple of dozen actors realistically depict a battle scene or the slaughter of thousands of Catholics by Robespierre’s terrorists? Worse still, the film’s director, Jim Morlino, had decided to use only child actors. Wasn’t this a recipe for disaster? Oh well, I thought as I hit the play button, if a thing is worth doing at all, it’s worth doing badly…

Fearing the worst, I found myself charmed by the film, and was moved to tears of sorrow for the fate of the martyrs of the Catholic Resistance but also to tears of laughter at the moments of comic relief.

As I watched the child actors playing husbands and wives, and even grandparents, I realized that you had to see the film through the eyes of a child in order to see it at all. This is emphatically not to suggest that the film is childish but that we adults have to become childlike in order to enter the kingdom of truth that the film presents to us. We have to suspend our disbelief, walking through the wardrobes of our imagination into a world where the eternal verities shine forth with innocence and wonder.

As I allowed my own imagination to wander through the wardrobe of wonder, I found myself, to my surprise, not in Narnia but in Middle-earth. The romantic and rustic depiction of life in the villages of the Vendée became, for me, a reincarnation of the Shire. Once this connection had been made, the child actors became hobbits, halflings who faced the French revolutionary dragons with an unsophisticated innocence. I am sure that something of this vision was in the mind of Morlino, who depicts the evil Robespierre as being demonically possessed, as no doubt he was. Robespierre is as unsophisticatedly evil as the peasants of the Vendée are unsophisticatedly good.

There is a price to pay for this unabashedly pure approach to the problem of evil, such as a loss of the nuanced niceties that historical accuracy demands (and should demand), but the price is well worth paying. Deep down, at the bedrock level of truth, the French Revolution was as evil as anything that the Fellowship of the Ring had to face. Its bloodthirsty secular fundamentalism set the scene for the bloodletting of the next two centuries. In its insatiable war on the Faith, secularism began with the guillotines and the Great Terror and metamorphosed into the Gulag and the gas chamber. Today, of course, it attacks the Faith and the Family and is systematically exterminating the weak and disabled members of society through the plague of abortion.

Make no mistake, Robespierre was one of Satan’s greatest servants and the villagers of the Vendée were certainly on the side of the angels. As such, we can be sure that both sides in this epic struggle between good and evil now have their reward. Robespierre would be killed by the same orcs that he had unleashed on the Vendée and his fate after death might be too horrible to contemplate. The heroic villagers of the Vendée, butchered in their thousands by the hordes of revolutionary orcs, are now in the company of the saints, martyrs and angels.

Posted on Jan 21st, 2013 in

History,

Politics,

West |

0 comments

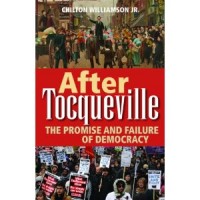

Twenty years ago, as the Cold War ended with the triumph of the West over Communism, Francis Fukuyama proclaimed the “end of history,” by which he meant that human political community had reached its final and best stage of development in the form of liberal democracy. Samuel Huntington spoke of a third great wave of democracy sweeping through eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia. But many of the new democracies were short lived, pulled down in an authoritarian undertow. History had a future after all.

Whether or not they agree with the specifics of Fukuyama’s claims, political scientists, policy analysts, and policy makers share his fundamental assumptions. They disagree chiefly over the means by which liberal democracy should be spread throughout the world. Though the experiences of the last decade have chastened advocates of promoting democracy around the world, support for liberal democracy remains the default position for U.S. foreign policy. Even when support for democracy undermines allies and facilitates the rise to power of anti-Western parties—that is, even when it seems to work contrary to the national interest—American administrations tend to stay faithful to promoting democracy.

That may be why Chilton Williamson, Jr. inclines toward defining democracy as a kind of religion. Williamson is a former literary editor of National Review, currently senior editor of Chronicles, and the author of several novels. He says that there is no generally accepted definition of democracy, and does not try to formulate one of his own, but seems to settle on characterizing it as a false religion that believes that the popular will should always prevail in government (pp. 73–74). If Williamson is right, his definition would go some way toward explaining why so many are blind to the weaknesses of contemporary democracy and the possibility of its demise: the inevitability and permanence of democracy is an article of faith.

The first part of Williamson’s book traces the history of modern democracy from American independence up to the present, focusing on the U.S. and Britain. He believes that democracies have best flourished in periods during which they were imperfectly democratic. Both American and British democracy experienced their golden ages when the franchise was broad but not universal, and when educated men of property played the leading roles in political life. By the late nineteenth century, this “aristocratic balance” was lost. During World War I governments mobilized their entire populations to fight and extended democracy more broadly than ever before. The war discredited European liberalism, which was blamed for the war and the weaknesses of multiethnic regimes that emerged from it. But the war did not discredit the democratic principle, which was pressed into the service of nationalism and socialism. It was only after World War II and the defeat of totalitarian National Socialism that liberal democracy was wholeheartedly embraced by peoples and governments. Until then, intellectuals were for the most part opposed to democracy. Men of letters as various as Stendahl, Matthew Arnold, Albert Camus, and T. S. Eliot expressed deep skepticism toward democracy. As Wyndham Lewis said, “No artist can ever love democracy.”

Williamson admires what Alfred Kahan called the aristocratic liberalism of Alexis de Tocqueville and others because they believed in popular government but were aware of its potential to threaten individual liberty, intellectual excellence, and the social bodies that make up civil society. While progressives of various stripes have sought to extend the principles of democracy from the political realm into civil society, conservatives have opposed this extension, believing with Tocqueville that nondemocratic social bodies in civil society counteracted dangerous tendencies in democratic politics. Williamson says that “it was in his fears, perhaps even more than in his hopes, that the author of Democracy in America proved himself to be a man of deep intuition and a true prophet of history” (p. 40). But Tocqueville is more a point of departure than an interlocutor for Williamson because democracy has changed so much from his day to ours.

Read the complete article in The University Bookman