Eugenio Corti, il cantastorie del Regno, by Giulia Tanel

La sera di martedì 4 febbraio Eugenio Corti ha fatto ritorno al Padre. Classe 1921, lo scrittore aveva conformato la sua vita al versetto del Padre Nostro che recita “Venga il Tuo Regno”, combattendo la buona battaglia tramite la scrittura.

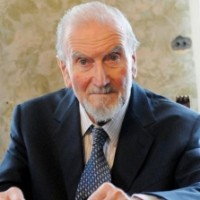

Uomo dal portamento distinto e dal fare pacato ma anche caparbio, Corti scrutava con i suoi attenti occhi azzurri i tanti lettori, molto spesso giovani, che si recavano a trovarlo nella sua casa in Brianza. Personalmente ricordo il suo atteggiamento vigoroso e paterno, dettato e supportato dalle decisive esperienze maturate durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale e da una fede granitica. Dialogando con lui si aveva la percezione di essere di fronte a un maestro da cui attingere preziose considerazioni sul passato e sull’epoca contemporanea; nel contempo, emergeva anche la consapevolezza di essere in presenza di una persona cui – da cattolici – guardare come modello di comportamento, perché lo sguardo di Corti, benché permeato di un sano realismo, era sempre orientato a Dio.

Non a caso, accanto all’età d’oro greca, il periodo storico più amato dallo scrittore brianteo era il Medioevo, ossia l’epoca in cui il messaggio cristiano si è diffuso in maniera capillare ed è diventato un fenomeno ‘di popolo’, dando luogo alla Res Publica Christiana. In quei secoli, troppo spesso classificati come ‘bui’ e invece ricchissimi sotto diversi aspetti, ogni ambito del vivere quotidiano era orientato – seppur con le dovute eccezioni – agli ideali del Vangelo: dal modo di concepire la guerra e la cavalleria, allo sviluppo dell’arte pittorica e architettonica, al ruolo assegnato alle donne… E proprio riguardo quest’ultimo aspetto, entrando nella casa di Corti si rimaneva piacevolmente colpiti dalla presenza riservata, ma assolutamente rilevante, di sua moglie Vanda, che lo scrittore contemplava ancora con sguardo innamorato e riconoscente, nonostante fossero sposati dal 1951.

Ma si diceva della centralità della fede nella vita e nel pensiero di Corti, la quale trova conferma anche nei suoi articoli e nei libri – molto vari per genere e argomento – ch’egli ha scritto dal 1947 in avanti. Tra questi spicca per importanza il romanzo storico Il Cavallo Rosso (Edizioni Ares, 1983), oramai giunto alla ventinovesima edizione e tradotto in otto lingue. Questo testo – che ha richiesto a Corti ben undici anni di lavoro – narra le vicende di alcuni ragazzi della Brianza e del loro incontro con il mondo esterno, sullo sfondo dei grandi avvenimenti storici succedutisi in Italia e nel mondo tra il 1940, anno dell’entrata in guerra dell’Italia, e il 1974, anno del referendum sul divorzio. Scorrendo pagina dopo pagina, moltissimi lettori sono rimasti avvinti nella narrazione e – oltre ad aver potuto rivivere quasi in presa diretta gli anni del secondo conflitto mondiale e della ricostruzione – hanno avuto modo di apprezzare le riflessioni storiche, teologiche e teleologiche che Corti non mancava mai di inserire nei propri scritti, in forma più o meno diretta.

Un’altra opera fondamentale lasciataci dallo scrittore brianteo è Il fumo nel Tempio (Edizioni Ares, 1996), una raccolta di articoli scritti dal 1970 in poi sulla difficile situazione della Chiesa nel post Concilio, sulla perdita di valori della società, sulla crisi della politica e in particolare della Democrazia Cristiana e, infine, sull’egemonia di una cultura di matrice laica e troppo spesso ideologizzata. Sono testi di una lucidità spesso disarmante, propria di un osservatore attento e onesto qual era Corti, convinto che il parametro di giudizio cui fare riferimento è sempre l’insegnamento di Cristo, perché solo in questo modo è possibile vivere in pienezza e gustare anche in terra un imperfetto assaggio di felicità e di Bellezza.

Sintomatica di quest’approccio alla vita è la risposta data da Corti alla domanda su quale fosse la cosa più bella che gli sia mai accaduta: «L’essere venuto al mondo, sicuramente. La prova è stata anche dura, come per tutti. Ma è stato l’esistere, l’essere, che mi ha aperto tutte le altre porte. Anche quella della consolante Speranza cristiana in una felicità intramontabile in Dio, dopo la morte terrena».

Al termine di una vita intensa e luminosa, la poesia posta da Eugenio Corti in calce alle 1274 pagine che compongono Il Cavallo Rosso appare quasi come un suo testamento: “Ecco, ora svaniscono, / i volti e i luoghi, con quella parte di noi che, come poteva, / li amava, / Per rinnovarsi, trasfigurati, in un’altra trama” (T.S. Eliot). Requiescat in pace!

Published in La nuova bussola quotidiana

Stand up for the real meaning of freedom, by Roger Scruton

When pressed for a statement of their beliefs, conservatives give ironical or evasive answers: beliefs are what the others have, the ones who have confounded politics with religion, as socialists and anarchists do. This is unfortunate, because conservatism is a genuine, if unsystematic, philosophy, and it deserves to be stated, especially at a time like the present, when the future of our nation is in doubt.

Conservatives believe that our identities and values are formed through our relations with other people, and not through our relation with the state. The state is not an end but a means. Civil society is the end, and the state is the means to protect it. The social world emerges through free association, rooted in friendship and community life. And the customs and institutions that we cherish have grown from below, by the ‘invisible hand’ of co-operation. They have rarely been imposed from above by the work of politics, the role of which, for a conservative, is to reconcile our many aims, and not to dictate or control them.

Only in English-speaking countries do political parties describe themselves as ‘conservative’. Why is this? It is surely because English-speakers are heirs to a political system that has been built from below, by the free association of individuals and the workings of the common law. Hence we envisage politics as a means to conserve society rather than a means to impose or create it. From the French revolution to the European Union, continental government has conceived itself in ‘top-down’ terms, as an association of wise, powerful or expert figures, who are in the business of creating social order through regulation and dictated law. The common law does not impose order but grows from it. If government is necessary, in the conservative view, it is in order to resolve the conflicts that arise when things are, for whatever reason, unsettled.

Read the complete article in The Spectator

A Noble Imagination: Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley, by James P. Bernens

If you would wish for your children to garner a love and fascination for the good things of God’s Creation, if you would have them embrace adventure, cherish what is noble, honor the poor, and attain to a sincere civility and gentleness, let them read from the works of Sir Walter Scott.

Born in 1771 in the city of Edinburgh, Walter Scott came of age in a century that had seen the uneasy political union of the kingdoms of England and Scotland, and was about to see the upheaval of the American and French Revolutions. Drawing from the deep well of British and medieval history, Scott established himself as one of the premier poets of his age, and one of the finest pure storytellers the English language has ever seen. His first novel, Waverley, remains once of his best, although it is less recognizable to modern readers than many other excellent titles like Ivanhoe and Rob Roy.

First published in 1814, Waverley is a lovely and heroic tale which follows the journey of young Edward Waverley, an impressible English gentleman and army officer, who is posted to duty in the tumultuous scene of eighteenth-century Scotland. Mindful of the old Royalist history of his own family, and carried on a string of fate that brings him into league with a Highland clan, Waverley becomes embroiled in the 1745 “Jacobite” rebellion, which seeks to replace Britain’s King George with the exiled Catholic Stuarts. If this chapter of British history sounds obscure, the reader may be comforted to know that much context is incorporated into the fabric of the story by the keen antiquarian mind of Sir Walter Scott himself.

More than anything, Waverley evolves into an adventurous ramble through the genteel courts and fearsome wilds of Scotland and England. There are portions of the novel which simply cannot be forgotten: as when Waverley stands enchanted by the Gaelic music of beauteous Flora Mac-Ivor; or when the rash hero suddenly finds himself pledging his sword in the service of the charismatic Jacobite leader, Bonnie Prince Charlie; or when the great Catholic Highland chieftain, the Vich Ian Vohr, manfully meets his end with the laughing phrase, “This is well got up for a closing scene.”

But the excellence of Waverley extends beyond the many opportunities for suspense and enjoyment which it affords the reader. Like much else that Scott wrote, it provides a lesson in poetry and healthy imagination, and reassures the observant mind of the goodness of the age-old morals. It was this quality in Scott’s writing which drew the special admiration of another venerable Briton, the famous Catholic convert John Henry Newman. In 1839, six years before his conversion to Rome, Newman wrote:

During the first quarter of this century a great poet [Scott] was raised up in the North, who, whatever were his defects, has contributed by his works, in prose and verse, to prepare men for some closer and more practical approximation to Catholic truth. The general need of something deeper and more attractive than what had offered itself elsewhere, may be considered to have led to his popularity; and by means of his popularity he re-acted on his readers, stimulating their mental thirst, feeding their hopes, setting before them visions, which, when once seen, are not easily forgotten, and silently indoctrinating them with nobler ideas, which might afterwards be appealed to as first principles.

Newman saw in Scott’s writing—of which Waverley is a foremost example—an excellence and superiority that helped move men’s minds towards a healthy Christian culture. For the same reason, Dr. Russell Kirk, writing in 1993, esteemed Sir Walter Scott as one of his ten exemplary conservatives in the history of Western Civilization.

Now, after all this has been said, you might be moved to ask: “If this is true, why have I heard and seen so little of the books written by this eminent Scotsman?”

Read the complete article in Crisis Magazine