When Pigs Fly and Monkeys Type, by Gerald Schroeder.

Stephen Hawking in his A Brief History Of Time taught the world that given enough time, monkeys hammering away on typewriters could type out a Shakespeare sonnet.

It is a nice adage but totally off base, at least within the reality of our world. Having gone to MIT I don’t know many sonnets. In fact when I thought about this I only knew the opening line of one, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day.” There are a bit fewer than 500 letters in that sonnet [All Shakespeare's sonnets are about the same length; all by definition 14 lines long.]

Let’s consider a grab bag with the 26 letters of the English language in it. I reach into the bag blindfolded and pull out a letter. The likelihood that it will be ‘s’ for the first letter of the sonnet is one chance in 26. The likelihood that in two draws I will get an ‘s’ and then an ‘h’ is one chance in 26 times 26. And so on for the 500 letters. Neglecting spaces between the words, the chance of getting the entire sonnet by chance is 26 multiplied by itself 500 times. That number comes out to be a one with 700 zeroes after it. In conventional math terms, it is 10 to the exponent power of 700.

To give a sense of scale for reference, the known universe including dark matter and black energy weighs in the order of 10 to the power 56 grams; the number of basic particles [protons, neutrons, electrons, mesons] in the known universe is 10 to the power 80; the age of the universe from our perspective of time, 10 to the power 18 seconds. Convert all the universe into micro-computers each weighing a billionth of a gram and run each of those computers billions of times a second non-stop from the beginning of time and we still will need greater than 10 to the power 500 universes, or that much more time for even a remote probability of getting a sonnet; any meaningful sonnet. Chance does not produce intelligible text and certainly not a sonnet, not in our universe.

But so convincing is the Hawking argument that the students at the Plymouth University in England convinced the National Arts Council to put up 1500 Sterling, about $3000, to try monkey typing skills. They rented a monkey house for a month. Six monkeys hammered away on a computer key board and failed to produce a single English word. Surprised, since the shortest word in the English language is one letter long? Surely the monkeys must have hit an ‘A’ or an ‘I’ in all their efforts. But think about it. To a make an ‘A’ a word requires a space on each side of the ‘A’. That means typing: space, ‘A,’ space. If there are about 100 keys on the computer key board, the probability is one chance in a 100 times 100 times 100 which comes out to be one chance in a million. Random guessing in a spelling bee is always a losing proposition. And that is for a single letter word.

But what about life? Could random mutations have actually produced the ordered complexity of life, or even a viable protein? Mutations that are to be passed on to the next generation must occur in the genetic material of the reproductive line, which is in the DNA of sperm or egg. That mutation results in a variant (mutated) protein which might produce a new more effective type of organ, say a better muscle or the beginning of a transition from fin to foot. That would be the neo-Darwinian concept. But let’s look at that process rigorously. When we do we’ll see it does not work if randomness is the only driving force.

Read complete article in Catholic Education Resource Center.

Why Study the West?, an interview with Robert P. George .

The new issue (Vol. 25, No. 1, March 2012) of Academic Questions, the excellent journal of the National Association of Scholars, is devoted to the study of Western civilization. It includes interesting articles by Charles Butterworth, Robin Fox, Stephen Balch, and others. It also includes an interview I gave to editor-at-large Carol Iannone.

=============

Why Study the West? An Interview with Robert George

by Carol Iannone, editor-at-large of Academic Questions

Iannone: Why is Western Civilization worth studying in your view?

George: By any standard of measure, the intellectual, moral, religious, political, economic, scientific, technological, artistic, architectural, and literary achievements of the West are extraordinary. It would be foolish not to study them, examine their roots, and explore the complex relationships among them, such as the relationship between Western religious ideas and the development of science. Our students are—as we ourselves are—inheritors of these achievements. Their culture—and, thus, their lives—have been shaped by them. They deserve to understand them. And if they are to maintain all that is worth maintaining, and reform what needs reforming, and pass along to their own children a vibrant and healthy culture, they need to understand them.

Iannone: What about Western Civilization is unique?

George: Science as we know it could not have developed outside of the West. It is a great gift of the West to the entire world. Moreover, ideas of natural law, republican government, civil rights and liberties, and the dignity, inviolability, and fundamental freedom of the individual are fundamentally Western insights. These, too, are gifts to the world. Many of these insights were hard-won. Some might yet be lost. Certainly, they have not always been honored, or fully respected, by the people of the West or their political, religious, and cultural institutions. Still, they are exceptional achievements.

Iannone: How important are Judaism and Christianity and the moral values they foster to the maintenance of Western Civilization? Are there other essential elements of Western thought that should be part of any curriculum—certain books, ideas, developments?

George: If there were no Judaism, there would be no Christianity. There is a profound sense in which Christianity is the “other” Jewish religion emerging from the transformations in Jewish faith and practice that resulted from the destruction of the second Temple in Jerusalem. If there were no Christianity, there would be no Western civilization. Most of the great achievements of the modern West were underwritten by Christian, and therefore also by Jewish religious and philosophical and moral ideas. Of course, pre-Christian Greek and Roman thought, many of the aspects of which were taken up into Christian thought, were also profoundly important. Can these achievements be maintained if Jewish and Christian faith collapses in the West? Can Western ideals and institutions flourish when utterly severed from their religious roots? Frankly, I doubt it. But it appears that we will know for sure before too long. Much of Europe today is engaged in a vast experiment that will tell us whether cultural and political achievements whose historical roots are in religion can be sustained and nurtured in a cultural and political milieu of extreme secularism.

Read complete interview in Mirror of Justice

Progressivism and the Younger Generation, by Mark Henrie.

As Sigmund Freud never said, the great unanswered question is: “What do conservatives want?” You must confess that it is a genuine question, because the characteristic conservative stance for the past two centuries has been one of opposition. We are more clear, and unified, about what we oppose than by what we propose. Stephen Holmes, in his self-congratulatory and ultimately fatuous book, The Anatomy of Antiliberalism, argued that there is no real theoretical substance to conservatism, because those called conservatives through the years have been trying to “conserve” too many contradictory things—sometimes absolute monarchy, sometimes constitutional monarchy, sometimes constitutional republics, sometimes free trade, sometimes protected trade, sometimes corporatist authoritarian regimes, etc. But if conservatives have changed their defensive front, it is perhaps because the Left has, through these same centuries, constantly changed its mode of attack: sometimes advocating enlightened absolute monarchs, sometimes constitutional republics, sometimes plebiscitary democracies, sometimes parliaments, sometimes executive agencies, and lately advocating the supremacy of constitutional courts and “global governance”—whatever that is. One might say that a sufficient response to Stephen Holmes is: tu quoque.

Conservatism has been a matter of opposition, of “standing athwart History yelling ‘Stop’!” But if this is true, then the nature of the opposition is a matter of the first importance. Just yesterday, it seems, our politics was structured by the divide between liberals and conservatives. Today, thanks in no small part to conservative success at diabolizing the L-word, we are invited to consider a politics structured by the divide between progressives and conservatives. Is this a distinction that makes any difference?

But I would like to take a third look, and consider the question of the progressive/conservative framing in light of the larger question, “What do conservatives want?” It seems to me that it is of the essence of conservatism to feel oneself on the losing side of history.

Continued (click here)

L’imposture Stéphane Hessel mise en pièces, par Guy Milliere

L’un des indices les plus navrants de l’état de déchéance intellectuelle, culturelle, et morale dans lequel est tombé ce pays est sans aucun doute le succès qui a été accordé à un non-livre, composé d’une poignée de mots stériles, porteurs d’une pensée absente.

Et ce succès a été immense. Il se poursuit jusqu’à ce jour.

Il a consacré un mot : l’indignation. Celle-ci n’implique pas nécessairement de trépigner sur place : elle peut consister apparemment à venir camper sur une place publique en disant qu’on s’indigne. Elle peut consister aussi seulement à adopter une posture. Elle n’implique pas d’analyse, pas de connaissance, pas de savoirs particuliers.

Elle n’implique pas même qu’on s’indigne de sujets qui mériteraient réellement l’indignation, voire davantage, comme les souffrances bien réelles des Kurdes, des Coptes d’Égypte, des Africains du Sud-Soudan ou du Darfour. Elle permet l’indignation sélective, celle qui permet de pratiquer l’antisémitisme à la mode, et le seul racisme toléré aujourd’hui en Europe occidentale : celui qui s’applique aux Juifs Israéliens.

Elle permet, même, d’approuver des pratiques qu’on réprouve lorsqu’elles s’exercent sur le sol européen : le terrorisme, par exemple, qui, dès lors qu’il est pratiqué par des Arabes contre des Juifs du côté de Jérusalem, devient follement exaltant.

Grâce à ce non-livre, l’indignation a son livre de chevet. Et, pour que le futur indigné ne se trompe pas, la couverture porte le mode d’emploi : « Indignez-vous ! » Il s’en est apparemment vendu plus de deux millions de copies. Il se lit en dix minutes et s’oublie instantanément, bien qu’il laisse dans l’esprit des traces très salissantes.

Read complete article in Les 4 Vérités Hebdo

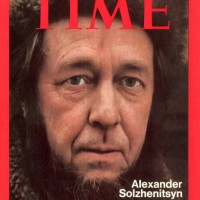

Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Address

A classic text from one of the greatest thinkers, writers and witness of the XXth Century.

A World Split Apart. Text of Address by Alexander Solzhenitsyn at Harvard Class Day Afternoon Exercises, Thursday, June 8, 1978.

here you can read about the background of the address in the Harvard Magazine