Tintin: The True European, by Peter Strzelecki Rieth

As Europe struggles with economic woes brought on by the combination of unrestricted government largess and corruption and avarice, it seems every thread of this current struggle emanates from the problem of European character and the concurrent angst surrounding it. A brief reflection on the problem of European character and an illustration of how centered it is at the causal crux of the European crisis may equip us to provide some solutions.

In brief, what I call the problem of European character and the concurrent angst surrounding it is the fact that the essence of the European Union, the modern European political project, is a negation of war between European nations. This means that the European character, if one can even speak of such a thing, is founded in the proposition that whatever happens, Europeans must remain united, for division inevitably leads to a war of all against all and the annihilation of European civilization. The founding event of this outlook was World War II. As such, there is no positive defining trait of European character, only a negation of war, which is to say that modern Europe is founded on the fear of being toward death. This special kind of glue holding the Union together is, to my mind, best defined using Heidegger’s concept of angst. Thus, when crisis strikes on account of numerous errors, a fear sets in against tampering with the ailing union as that may lead to its collapse and to war. Yet to do nothing, or as some quarters are urging, to strengthen the faulty bonds of union even further, will lead also to collapse and war because it will deepen the crisis and give rise to public aggravation and revolutionary fervor. The diagnosis is clear: the European Union, which arose from the common European character trait of angst, cannot sustain itself by angst. The European character must be enriched with positive traits or be undone.

Some “Euro-enthusiasts” may well now shake their heads and claim that this expanded, positive European character already exists, made visible in the thousands of pages of regulations instructing the citizenry on how to be tolerant, open-minded humanitarians who love mother Earth, their fellow man, and embrace science. The chief problem with this view, abstracting from the philosophical questions that arise regarding the desirability of this particular modern, ahistorical, and secular European character, is that it resides in regulations, not in the heart of the people. Regulation lacks the personal import even of law. The importance of this distinction is such that regulation dictates the minutiae of everyday life. It not only prescribes an ethos, as law does, it dictates the precise, quantified application of said ethos. Civilizations which are built on virtues, whether piety or tolerance, that are mandated, registered, stamped, and stipulated in paragraph 16, subsection 2 of the revised revision of the regulations revising previous revisions–such civilizations die.

Here, angst will worry: does it therefore follow that Europeans are destined to fall back on national and ethnic prejudices? Perhaps there are other alternatives available to them besides secular, liberal sophistication masking bureaucratic banality or some pompous nationalist stereotypes. Certainly the philosophers present us with numerous alternatives, though all of them might well be impractical for any landmass not populated by a majority of philosophers. We also cannot, it appears to me, reach far back into European history, for to expect of modern Europeans to adopt Roman virtue, Athenian wisdom, let alone Christian agape, may well be expecting too much. If we wish to look for something in modern European history grounded in a firmer basis than philosophical speculation then I suggest we look no further than Tintin.

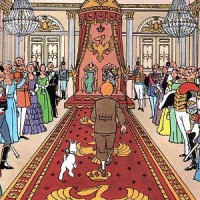

Tintin, for those who do not know and love him, is the European par excellence, created by author Hergé. His authority is widely acknowledged by children throughout the world, regardless of their age. General DeGaulle apparently called Tintin his only international rival. Tintin, if one really thinks about it, is the perfect template for a European character rooted in positive traits rather than merely in angst. Rather menacingly, the present generation risks knowing Tintin not through his European manifestation, but through the rather poor interpretation of his adventures presented to the world by the American director Steven Spielberg. All the more reason why I shall now endeavor to make a composite defense of Tintin as being of paramount importance and relevance to the present crisis.

First, Tintin has proven himself a keen political realist. I begin with this because some may well now expect me to embark on platitudes regarding Boy Scout virtues as exemplified by Tintin, rather than say anything of hard-nosed relevance to the grave situation Europe faces. Quite the contrary! It was Tintin, who, back in 1929, exposed the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union and the plight of its people at a time when the vast majority of Western opinion was either ignorant of or fascinated with the Soviet system. Tintin’s revelations were, for decades, characterized as childish caricatures until the publication of the Black Book of Communism made the broad public aware of what Tintin had reported as fact from the very outset. This, if nothing else, qualifies Tintin for serious consideration as a relevant voice in European affairs: where so many were wrong about the Soviet Union, he was right from the beginning.

Detractors will no doubt point out that Tintin may well have been stunningly right in his premiere journalism, but quickly followed up on that by being stunningly wrong in his treatment of European colonialism. From his wholesale slaughter of the helpless species populating the Congo, to his insensitive remarks to a room full of Congolese regarding their homeland “Belgium”, one quickly can see why these detractors may feel it quite a bad idea to hold Tintin up as a worthy ideal for European character. Why, at one point, Tintin even helped a Priest!

Yet the measure of ideals is not their perfection, but rather how they deal with their all too human imperfections. In the case of young Tintin in Congo, he did what he could to help the native populations, while everything we might be tempted to fault him for was, as author Hergé admitted, the result of not taking his work too seriously at the time and being unreflective about the prejudices of his age. Out of all of Tintin’s remarkable adventures, his sojourn through the Congo may be most fraught with vices, but we can take heart that Tintin learned from his mistakes, as we can see in his escapades in the Far East shortly after leaving the Congo. There, Tintin so exemplified courageous virtues in his gallant struggle to aid the Chinese in their time of desperation as to have earned the praise of Chiang Kai-Shek himself, not to mention endearing himself to the Dalai Lama, who to this day declares his love for the boy reporter.

This evolution from a rhino-hunting, crocodile-dynamiting, Al Capone-chasing adventurer into a serious young man of high moral principle and gallant instinct betrays a character trait sorely lacking in the modern European. The modern European is nihilistic in private, bureaucratic in public. Tintin, by contrast, demonstrated a a playful lightness and joi de vivre in his private life combined with moral conscience in public life. Tintin’s youth, his evolution, is not linear, but rather curvilinear. In the beginning, he fluctuates between noble deeds like helping the Indians by fighting exploitative Americans and lighthearted slap stick. Yet as Tintin’s experience of the world grows, his moral imagination is refined and his humor matures. The latter is actually tied intimately with the former, as moral reflection is quite impossible without humor. Only a character type like that of Tintin’s could permit such an evolution, and only a European of such character could hope to escape the trap of modern European Union: the prospect of despotic union or war, both laced with angst.

Tintin’s political teaching does not, however, stop there. He provides us with a wonderful illustration of the folly of radical factionalism and demonstrates how it is always the mother of despotism. How memorable his misadventures are in the banana republic of Generals Alcazar and Tapioca, where revolutions take place on a daily basis, where the people oscillate between wild revolutionary fervor and grinding tyranny, where no matter who wins, dictatorship and poverty remain constant. The illustration, although set in a South American context, certainly does tell us quite a bit about human nature and the folly of revolutions. Far from being a means towards salvation from tyranny, Tintin seems to teach us that strife, faction, and partisan division are a direct route to tyranny. Civilized people, in contrast to the banana republics, Tintin suggests, never engage in revolution but rather rely on other means. Revolutions appear an easy solution, but end up solving nothing while expending the accumulated public stock of disappointed hope.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative