Posted on Jun 19th, 2012 in

Academy,

Philosophy |

0 comments

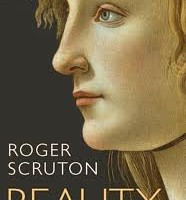

In 1900, Henry Adams “haunted” Paris’s Exposition Universelle, “aching to absorb knowledge, and helpless to find it.” He came to realize that the new idols of the modern world exuded power but not beauty; that the new world would not be defined by animate spirit but rather impersonal motion; that the useful would be more admired than the sacrosanct. Human prowess was fully apparent at the Great Exposition, but the ideas which inspired men to build the great cathedrals were becoming extinct; the future would be embodied in other objects of admiration, like the steam engine. Now, more than a century after Adams plumbed the loss of sacred sensibilities that would define the modern and postmodern eras, Roger Scruton has written a book (entitled Beauty, with no subtitle) to explain why we need our sense of the sacred back.

As conservative as he is prolific, Scruton admits that beauty is grounded in experience but, nonetheless, concludes that “everything [he has] said about the experience of beauty implies that it is rationally founded.” Aesthetic theory determines this rational basis, but Scruton declines to articulate any set of principles or axioms. This is perhaps just as well, since conservatives have always placed more emphasis on the concrete than the abstract.

Some of the most memorable passages in the book occur, in fact, when Scruton questions and refutes the arguments of those who attempt to turn beauty into an abstraction. In a digression on the theories of the architect Louis Sullivan, Scruton points out that Sullivan’s view that beauty follows from the function it serves ultimately fails to live by its own standard, since a change of context can turn functional qualities into aesthetic ones: the factory blocks of Brooklyn, for instance, were not beautiful until they ceased to function as factories and were transformed into lofts and art studios. Scruton similarly rebuts anthropological theories of the beautiful which, rather than attempting to explain beauty, try to explain it away. He points to the fact that these theories—such as that of Ellen Dissanayake, which explains aesthetic experience as an anthropological phenomenon through which ceremonies or objects become subjectively “beautiful” to make them distinct—fail to provide an account of what it is that makes the beautiful unique. He writes, “Although the sense of beauty may be rooted in some collective need to ‘make special,’ beauty itself is a special kind of special, not to be confused with ritual, festival or ceremony, even if those things may sometimes possess it.”

Scruton remains largely true to the point that he illustrates at the end: that our experience of beauty cannot be understood apart from what our instinct or experience suggests “looks right,” whether this be (to stay close to his own examples) in high art or in something as simple as a balanced doorframe or a meticulously arranged table-set. But he does not ignore the general characteristics associated with aesthetic judgment. As he is in Scruton’s works on moral philosophy, Immanuel Kant is deployed as a valuable resource. Kant’s contention that aesthetic pleasure is disinterested in nature, or based upon pure reason rather than bound up in what the object of pleasure can do for the observer of it, does not provide us with any specific definition of what the beautiful is, but it does offer a criterion to determine how we can know when we are having an aesthetic experience (as opposed to some other kind of experience of admiration or attraction or pleasure).

Leave a comment