The Hook of Truth, by Gerard Kreijen

A review of Edmund Campion: A Life by Evelyn Waugh (Ignatius Press, 2005 [First published by Longmans, 1935])

That the undisputed master of dark humor and satire should have produced what is arguably the most compelling short biography of a saint to date is perhaps even more extraordinary than the claim that, today, both the biography and its author deserve close attention. Indeed, few means serve better to confront the hollow relativism of our age than turning to the conversion of Evelyn Waugh (1903-1966) and the life of Edmund Campion (1540-1581), the saintly subject of his 1935 book.

When Waugh was received into the Roman Catholic Church on September 29, 1930 his latest book had just been dubbed “the ultramodern novel”, so that his conversion caused sensation and bewilderment. In an article entitled, “Converted to Rome: Why It Has Happened to Me”, Waugh made it perfectly clear that his decision was not about ritual nor about submission to the view of others. The essential issue was the choice between Christianity and chaos.

Waugh had come to see Modernity as “the active negation of all that Western culture has stood for”. Civilization, he understood, “has not in itself the power of survival”. Christianity was the foundation of the West and without it the moral and aesthetic fabric of Europe would unravel. For Waugh this was a fact and the acknowledgment of this fact set him against modern society; it was his casus belli:

“The loss of faith in Christianity and the consequential lack of confidence in moral and social standards have become embodied in the ideal of a materialistic, mechanized state […] It is no longer possible […] to accept the benefits of civilization and at the same time deny the supernatural basis upon which it rests. “[1]

Thus Waugh turned “from ultramodern to ultramontane, and in doing so passed from fashion to anti-fashion”.[2] He became, as George Orwell quipped, “about as good a novelist as one can be while holding untenable opinions”.[3] In his literary attempts to represent man more fully, which for Waugh meant “only one thing, man in his relation to God”[4], he focused on the theme of the redemption of lost souls – notably, in his celebrated novel Brideshead Revisited (1945). Redemption, Waugh later explained with a reference to G.K. Chesterton, may be compared “to the fisherman’s line, which allows the fish the illusion of free play in the water and yet has him by the hook; in his own time the fisherman by a ‘twitch upon the thread’ draws the fish to land”.[5]

One gathers why Waugh wrote a life of Edmund Campion, the respected Oxford scholar who fled Elizabethan England amidst the troubles of the Reformation and who returned as a Jesuit priest to “crie alarme spiritual against the foul vice and proud ignorance, wherewith many my dear countrymen are abused”, finally to meet a martyr’s death at Tyburn.

Read complete article in The Clarion Review

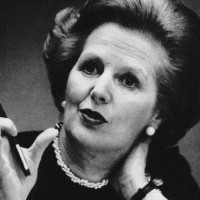

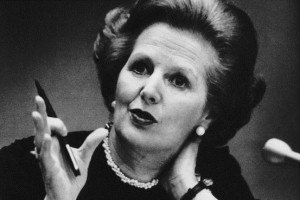

“The Real Margaret Thatcher Story”. Daniel Yergin

In the late 1970s, inflation neared 20% and the ruling party still wanted to own the means of production. Enter the grocer’s daughter.

A movie producer once shared with me a maxim for making historical films: Faced with choosing between “drama” and “historical accuracy,” compromise on the history and go with drama.

That is certainly what the producers of “The Iron Lady” have done. The result is a masterly performance by Meryl Streep as former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. But the depiction of Mrs. Thatcher in the movie misses much of the larger story. That story—the struggle to define the frontier between the state and the market, and the calamities that happen when governments live beyond their means—is directly relevant to the debt dramas now rocking Europe and the United States.

After World War II, Britain created the cradle-to-grave welfare state. A clause in the constitution of the Labour Party which came to power in 1945 called for government to own the “means of production.” That ended up ranging from coal mines and the steel industry to appliance stores, hotels and even a travel agency.

The postwar “mixed economy” became a recipe for economic decline. Inflexible labor rules and competition for power among unions led to endless strikes and disruption of the economy. Workers in state-owned companies were essentially civil servants, which gave them enormous clout when they struck. The system stifled innovation, adaptation and productivity, making Britain uncompetitive in the world economy. Yet the spending and debt to support an expansive welfare state went on.

By the late 1970s, enormous losses were piled up at state-owned companies, debts which had to be covered by the British Treasury. A desperate Britain needed to borrow money from the International Monetary Fund. Inflation was heading toward 20% as the deficit mounted and strike after strike disrupted economic life. Even grave diggers walked off the job. The continuing deterioration of the country seemed inevitable. Some predicted that Britain would soon be worse off than communist East Germany.

Enter Margaret Thatcher, the daughter of a grocery-shop owner who had begun her own professional life as a food chemist but decided she preferred politics to working on ice cream and cake fillings. In 1975, she was elected leader of the Conservative Party. Four years later, she became prime minister, determined to reverse Britain’s decline. That required great personal conviction, which Meryl Streep brilliantly captures.

Mrs. Thatcher came with her own script, a framework provided by free-market economists who, even a few years earlier, had been regarded as fringe figures. One telling moment that “The Iron Lady” misses is when a Conservative staffer called for a middle way between left and right and the prime minister shut him down mid-comment. Slapping a copy of Friedrich Hayek’s “The Constitution of Liberty” on the table, she declared: “This is what we believe.”

Years later, when I interviewed her in London, Mrs. Thatcher was no less firm. “It started with ideas, with beliefs,” she said. “You must start with beliefs. Yes, always with beliefs.”

As prime minister, she encountered enormous resistance, even from her own party, to putting beliefs into practice. But she prevailed through difficult years of painful budget cuts and yanked the government out of loss-making businesses. Shares in state-owned companies were sold off, and ownership shifted from the British Treasury to pension funds, mutual funds and other investors around the world. This set off what became a global mass movement toward privatization. (“I don’t like the word” privatization, she said when we met. What was really going on, she said, was “free enterprise.”)

But it was labor relations that were the great drama of the Thatcher years. The country could no longer function without labor reform. This was particularly true of the government-owned coal industry, which was being subsidized with some $1.3 billion a year. The Marxist-led coal miners had great leverage over the entire economy because coal was the main source for generating Britain’s electricity. Everyone remembered the paralyzing 1974 National Union of Miners strike which blacked out the country and brought down a Conservative government.

By the 1980s, it was clear that another confrontation was coming as Mrs. Thatcher’s government prepared to close some of its unprofitable mines. The strike started in 1984 and was marked by violent confrontations. But the Iron Lady would not bend, and after a year the strike faltered and then petered out. Thereafter, the road was open to reformed labor relations and renewed economic growth.

In 1990, discontented members of the Conservative Party did what the miners could not and brought Mrs. Thatcher down. The Iron Lady, in their view, had become the Imperious Lady of domineering leadership. They revolted, forcing her to resign.

Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were intellectual soul mates, but the movie does not touch on arguably their greatest collaboration, which was ending the Cold War. Mrs. Thatcher’s visit to Poland in 1988, for instance, gave critical impetus to the Solidarity movement in its struggle with the Communist government.

But the difference between how Reagan and Mrs. Thatcher are seen today is striking. The bitterness of the Reagan years has largely been forgotten. Not so with Margaret Thatcher. She remains a divisive figure. Her edges were sharp, as could be her tone. Moreover, she was a woman competing in what had almost completely been a man’s world.

Yet her true impact has to be measured by what came after, and there the effect is clear. When Tony Blair and Gordon Brown took the leadership of the Labour Party, they set out to modernize it. They forced the repeal of the party’s constitutional clause IV with its commitment to state ownership of the commanding heights of the economy.

They did not try to reverse the fundamentals of Thatcherite economics. Mr. Blair recognized that without wealth creation, the risk was redistribution of the shrinking slices of a shrinking pie. The “new” Labour Party, he once said, should not be a party that “bungs up your taxes, runs a high-inflation economy and is hopelessly inefficient” and “lets the trade unions run the show.”

The lesson that governments cannot permanently live beyond their means had been learned. When economies are growing in good times, that lesson tends to be forgotten. Yet the longer it is forgotten, the more painful, contentious and dangerous the relearning will be. That is the real story of the Iron Lady. And that is the story in Europe—and the U.S.—today.

Mr. Yergin is author of “The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World” (Penguin 2011) and chairman of IHS CERA.