Solzhenitsyn’s Prophetic Voice: Biographer Joseph Pearce Discusses Critic of Communism, by Annamarie Adkins & Joseph Pearce

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, some people predicted that global affairs had reached “the end of history” and that democratic capitalism had definitively triumphed.

Solzhenitsyn: The Courage to be a Christian, by Joseph Pearce.

In these dark days in which the power of secular fundamentalism appears to be on the rise and in which religious freedom seems to be imperiled, it is easy for Christians to become despondent. The clouds of radical relativism seem to obscure the light of objective truth and it can be difficult to discern any silver lining to help us illumine the future with hope.

In such gloomy times the example of the martyrs can be encouraging. Those who laid down their lives for Christ and His Church in worse times than ours are beacons of light, dispelling the darkness with their baptism of blood. “Upon such sacrifices,” King Lear tells his soon to be martyred daughter Cordelia, “The gods themselves throw incense.”

It is said that the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church and, if this is so, more bloody seed has been sown in the past century than in any of the bloody centuries that preceded it. Tens of millions have been slaughtered on the blood-soaked altars of national and international socialism in Europe, China, Cambodia and elsewhere. Today, in many parts of the world, millions upon millions are being slaughtered in the womb in the name of “reproductive rights.”

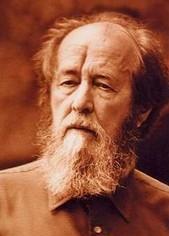

In such a meretricious age the giant figure of Alexander Solzhenitsyn emerges as a colossus of courage. Born in Russia in 1918, only months after the secular fundamentalists had swept to power in the Bolshevik Revolution, Solzhenitsyn was brainwashed by a state education system which taught him that socialism was just and that religion was the enemy of the people. Like most of his school friends, he enslaved himself to the zeitgeist, became an atheist and joined the communist party.

Serving in the Soviet army on the Eastern Front during the Second World War he witnessed cold blooded murder and the raping of women and children as the Red Army took its “revenge” on the Germans. Disillusioned, he committed the indiscretion of criticizing the Soviet leader Josef Stalin and was imprisoned for eight years as a political dissident.

While in prison, he resolved to expose the horrors of the Soviet system. Shortly after his release, during a period of compulsory exile in Kazakhstan, he was diagnosed with a malignant cancer in its advanced stages and was not expected to live. In the face of what appeared to be impending death, he converted to Christianity and was astonished by what he considered to be a miraculous recovery.

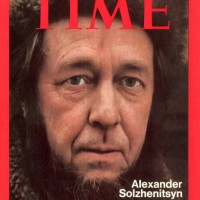

Throughout the 1960s Solzhenitsyn published three novels exposing the secularist tyranny of the Soviet Union and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. Following the publication in 1973 of his seminal work, The Gulag Archipelago, an exposé of the treatment of political dissidents in the Soviet prison system, he was arrested and expelled from the Soviet Union, thereafter living the life of an exile in Switzerland and the United States. He finally returned to Russia in 1994, after the collapse of the Soviet system.

In 1978, Solzhenitsyn caused great controversy when he criticized the secularism and hedonism of the West in his famous commencement address at Harvard University. Condemning the nations of the so-called free West for being morally bankrupt, he urged that it was time “to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.”

Read the complete article in Crisis Magazine

Solzhenitsyn, Russell Kirk, and the Moral Imagination, by Edward E. Ericson, Jr.

In the summer of 2003, I had to vacate my college office. With limited file-cabinet space at home, I had to lighten my files drastically. Reading and skimming my way along, I relived many episodes, including ones that I had quite forgotten. Also, I came upon old essays and reviews by various hands. One said in part, “Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn primarily is a man of moral imagination.” The author was none other than Russell Amos Kirk, and the citation came from his review of my 1980 book Solzhenitsyn: The Moral Vision.

As I reread that review, I was happily put in mind once again of the important influence that Russell Kirk had exerted upon me. To be sure, influence does not yield xerox-copy duplication. Kirk’s Gothic imagination, with its ghosts and gargoyles, has no deep hold on my affections. Nor has this Chicago native fallen under the sway of what I shall call his rural romanticism. But I did at that moment begin trying to articulate for myself the nature of my indebtedness to Kirk.

Clearly Kirk’s influence on me is best understood as that deep sort of influence that I lose track of consciously as my own mental activities continue apace. Gradually, I came to think of certain ideas learned from him as my own intellectual property. Even when my gestalt of these ideas resembles his, they get fitted together with other ideas of mine so that they are no longer his. As a simple example, when I say “tradition,” the word does not have all the associations for me as a Protestant that it does for Kirk, a Catholic. I have of course, as a reading person, picked up strands of thought from many sources and worked them into the tapestry of my world view. What separates Kirk from other sources is that the ideas I gleaned from him are part of the foundation of my intellectual life. They are part of the filter through which ideas from other sources must pass before I integrate those ideas into my personal point of view. Imagine my intellectual life as a long train-ride. What I am not thinking about is the material comprising the tracks on which the train is riding. The tracks are just there, and taken for granted. If we think of the tracks as an alloy of multiple materials, then in my case some of the tracks’ strongest materials are Kirk’s ideas. Thus he is an essential part of my intellectual journey even when I am not aware of it—and perhaps especially then. I was riding on those tracks when Solzhenitsyn first came into my view.

In that aforementioned review, Kirk writes, “The purpose or end of humane letters is ethical: a point forgotten by most writers and reviewers nowadays.” And he specifies that “Solzhenitsyn’s great concern is the moral state, rather than the political state.” Then he aligns Solzhenitsyn with T. S. Eliot: “Like Eliot, Solzhenitsyn sets his face against both the dread tyranny of Communism and the ‘Western’ infatuation with sensual satisfactions, and trifling material possessions.” This leads to Kirk’s next observation: that “Solzhenitsyn’s moral vision is what Eliot called the ‘high dream’—the vision of Dante, the Christian extrasensory perception of true reality. Even more than Dante, Solzhenitsyn passed through the Inferno, and was purged of dross.”

These references demonstrate that Kirk, too, however seminal his thinking has been for many of us, absorbed influences from predecessors, as he readily acknowledged, and we also observe how he fit new material—here Solzhenitsyn—in with old—here Eliot and Dante. That is, in fact, exactly how Eliot himself explains that tradition and the individual talent fuse, as a new writer draws upon predecessors and then by his contribution enlarges and enriches the tradition by becoming part of it. But what is more striking to me, as the author of the book that Kirk was reviewing, is that rereading this review made even clearer than before how Kirk’s influence prepared me for Solzhenitsyn. I have written little about Kirk, who has many expositors who get him right, and much about Solzhenitsyn, who has many expositors who get him wrong.

While engaged in the housekeeping chore of file-thinning, I realized that I would never have started writing about Solzhenitsyn if I had not first read my Kirk. I have not often used the formulation “moral imagination,” but my first book on Solzhenitsyn was subtitled The Moral Vision, and in my second book on him the second, and perhaps best, chapter is entitled “The Moral Universe.” One would not need to have read Kirk to see that Solzhenitsyn is a moral writer. But I had read Kirk, and he helped shape the mind that I brought to the reading, and then to the cherishing, of Solzhenitsyn. Indeed, I would say that in Solzhenitsyn I found literary renditions of the abiding, perennial values that Kirk had articulated for me.

The subject about which knowing my Kirk best prepared me to appreciate Solzhenitsyn was the subject of ideology. I recall an argument that raged among conservatives at one long-ago time about whether conservatism was an ideology or not. Kirk said not. As I followed the argument among my betters, with each side populated by writers whose ideas had helped me, I concluded that Kirk was right. Although time has dimmed my memory of the details of the argument because I came to a settled conviction on the matter, I agree with him that conservatism, far from being an ideology, is a negation of ideology. Then I came to Solzhenitsyn, and one confirmation of our consanguinity was his rejection of ideology—not just Marxist ideology but ideology per se. Both Kirk and Solzhenitsyn saw ideology as rooted in utopian thinking and avoided that loose usage common today that employs the term ideology to refer to any well-developed perspective, or world view.

One can imagine, then, how I shrink in mild horror when I hear people refer to “our” Christian ideology and “our” Reformed ideology. These are worse formulations than “conservative ideology.” I want to tell them to read Kenneth Minogue’s book Alien Powers: The Pure Theory of Ideology (1985), in which he defines ideology as “the propensity to construct structural explanations of the human world” and uses the word ideology “to denote any doctrine which presents the hidden and saving truth about the evils of the world in the form of social analysis.” And so I brought Minogue into my writing to elucidate Solzhenitsyn’s careful usage of the term ideology. Imagine my delight, then, to find on page four of Kirk’s The Politics of Prudence (1993), that Kirk cites Minogue, too. In Kirk’s words, ideology “usually has signified a dogmatic political theory which is an endeavor to substitute secular goals and doctrines for religious goals and doctrines.” He adds, “Ideology, in short, is a political formula that promises mankind an earthly paradise.” And so he calls ideology “inverted religion.” It is precisely in that sense that Solzhenitsyn offers as his synonym for ideology the words “the lie.”

The Politics of Prudence is Kirk’s summation of his thinking pulled together mainly for students; and, among much else, it makes clear his awareness of kinship with Solzhenitsyn. When he lists ten modern events “in which the conservative cause retained or gained some ground,” he includes Solzhenitsyn’s forced relocation from the Soviet Union to the United States. Why did Kirk think this event was important? Because it made Solzhenitsyn a participant in America’s cultural life, and his “denunciation of the tyranny of ideology did more to dispel illusions—although not from everybody’s vision—than did any other writing of our time.”

Kirk also cites a passage from Solzhenitsyn’s most overtly religious statement, the address given on the 1983 occasion of his receiving the Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion, an award set up to fill a gap in the roster of Nobel prizes. Predictably, this speech has received little notice from critics, and I quote in full the passage that Kirk cited.

“Our life consists not in the pursuit of material success but in the quest of worthy spiritual growth. Our entire earthly existence is but a transition stage in the movement toward something higher, and we must not stumble or fall, nor must we linger fruitlessly on one rung of the ladder. . . . The laws of physics and physiology will never reveal the indisputable manner in which the Creator constantly, day in and day out, participates in the life of each of us, unfailingly granting us the energy of existence; when this assistance leaves us, we die. In the life of our entire planet, the Divine Spirit moves with no less force: this we must grasp in our dark and terrible hour.”

Kirk describes this passage as “express-[ing] with high feeling the essence of the conservative impulse.” What does that mean? The passage is, of course, not in the least political, and Kirk is too wise to be claiming the Russian author for a political position within the American context. On the contrary, Kirk is recognizing the congruity between Solzhenitsyn and him at the deepest levels of their thinking. For both of them, meaning in human life lies ultimately in the transcendent realm, and only by reference to this transcendent source of meaning can the nature of human beings and human society be properly understood. In this passage Solzhenitsyn is also asserting his faith in Providence. And it belies the ludicrous suggestion that he is a Deist. The God in whom Solzhenitsyn believes is not remote and removed from human affairs but is personally active in human history and in individual lives. This is what Kirk sees as lying at the heart of the conservative impulse.

Another chapter in The Politics of Prudence lists “Ten Conservative Principles.” The one leading the list most readily brings Solzhenitsyn to mind. “First, the conservative believes that there exists an enduring moral order. That order is made for man, and man is made for it: human nature is a constant, and moral truths are permanent.” Solzhenitsyn, too, emphasizes constancy and permanence: “Human nature, if it changes at all, changes not much faster than the geological face of the earth.” As a writer he is fundamentally concerned with what he calls “the timeless essence of humanity,” as well as with those “fixed universal concepts called good and justice.”

Of all Kirk’s formulations that put me in mind of Solzhenitsyn, my favorite one comes from before Kirk was aware of Solzhenitsyn. In the opening pages of The Conservative Mind (1953), Kirk asserts, “Conservatives believe that a divine intent rules society as well as conscience, forging an eternal chain of right and duty which links great and obscure, living and dead.” Later in that seminal book, when enumerating the chief problems facing conservatives, Kirk mentions as the first one “the problem of spiritual and moral regeneration: the restoration of the ethical system and the religious sanction upon which any life worth living is founded.” And he remarks, in words that I cherish, “This is conservatism at its highest.” Not only would Solzhenitsyn resonate with these terms; the very words he chooses are often very close to Kirk’s diction, though apparently without ever reading Kirk. Clearly, reading Kirk prepared me to appreciate Solzhenitsyn.

The concept of the moral imagination means more to Kirk than to Solzhenitsyn. Kirk puts the term right into the title of his memoirs, The Sword of Imagination (1995). I have counted the references to imagination in that book’s index and come up with the number forty-one, ten of them referring specifically to the moral imagination. Imagination is mentioned more often than Catholicism, Communism, Liberalism, even Conservatism. The memoirs, too, help prepare us to apply the term “the moral imagination” to Solzhenitsyn. For example, when Kirk describes the purpose of The Conservative Mind, he says that “he meant to wake the moral imagination through the evocative power of humane letters” and thus that this book, though often approached as a political manifesto that gave rise to a whole movement, the American conservative movement, in fact belongs to the category of belles lettres. And so he describes himself as “more poet than professor.” He is, in sum, a literary man—or, in an older term seldom used nowadays, a “Man of Letters.” As a corollary, literature is the genre of writing best suited to convey the moral imagination. The memoirs also provide direct sanction for approaching the writer Solzhenitsyn as one who conveys it. In Kirk’s exact words, “ . . . through tribulations, Solzhenitsyn has developed that sort of political imagination urgently required in America near the end of the twentieth century—and that sort of moral imagination, too.”

For Kirk’s definition of the abstract term “the moral imagination,” we turn to his book on T. S. Eliot, Eliot and His Age (1971). There, after noting that the phrase is originally Edmund Burke’s, Kirk explains, “By it, Burke meant that power of ethical perception which strides beyond the barriers of private experience and events of the moment.” Our age places a premium on the autonomous Self and the subjective insights that emerge from raw, indiscriminate experience; our age also devalues tradition and favors presentism, or present-mindedness. And when Kirk remarks that “[t]he moral imagination aspires to the apprehending of right order in the soul,” our leading lights would reply that there is no such thing as soul and those who think there is should keep their religious gibberish to themselves as a private matter. Why, one may ask, does not Kirk just say right out that the moral imagination has “its roots in religious insights” and claim that, by possessing this vaunted faculty, “the civilized being is distinguished from the savage by his possession of the moral imagination”? Those things are exactly what he says, verbatim.

Read complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Aleksandr Solzenicyn e il cammino dell’”io” alla verità, di Giovanna Parravicini.

Vedendo tutta Mosca riscuotersi dal grigio torpore e accalcarsi intorno alle edicole per strappare una copia di «quella rivista dov’è scritta la verità» (nel novembre 1962 il prestigioso mensile Novyj mir pubblicava Una giornata di Ivan Denisovic, il primo racconto sui lager), giustamente Sergej Averincev osservava: «Questa ormai non è più solo storia della letteratura – è storia della Russia». La grande letteratura russa, del resto, non si è mai concepita solo come un fenomeno letterario, si è sempre sentita investita di una vocazione morale e pedagogica nel senso più elevato della parola, e così è sempre stata recepita dai suoi lettori, che potevano recitare senza esitazioni, come preghiere, accanto ai salmi le poesie del Dottor Zivago.

Vedendo tutta Mosca riscuotersi dal grigio torpore e accalcarsi intorno alle edicole per strappare una copia di «quella rivista dov’è scritta la verità» (nel novembre 1962 il prestigioso mensile Novyj mir pubblicava Una giornata di Ivan Denisovic, il primo racconto sui lager), giustamente Sergej Averincev osservava: «Questa ormai non è più solo storia della letteratura – è storia della Russia». La grande letteratura russa, del resto, non si è mai concepita solo come un fenomeno letterario, si è sempre sentita investita di una vocazione morale e pedagogica nel senso più elevato della parola, e così è sempre stata recepita dai suoi lettori, che potevano recitare senza esitazioni, come preghiere, accanto ai salmi le poesie del Dottor Zivago.

Il romanzo incompiuto di Solzenicyn Ama la rivoluzione!, finora inedito in Italia ma pubblicato ora dalla milanese Jaca Book, per la cura di Sergio Rapetti, a oltre cinquant’anni dalla sua composizione, ripropone questa grande lezione registrando, sullo sfondo del gigantesco dramma della seconda guerra mondiale, lo svolgersi di un altro dramma: il faticoso ma inarrestabile cammino dell’«io» umano verso la scoperta della verità, passando dagli slogan altisonanti e vacui dell’utopia («La vita era bellissima. In primo luogo perché era sottomessa alla volontà di Nerzin che poteva disporne a suo piacimento [...]. Era cresciuto nella convinzione che ogni uomo debba forgiare da sé il proprio destino»), al terreno aspro e accidentato, ma solido, della realtà («[…] quello sguardo di migliaia, inflessibile, cupamente testardo ma che senz’altro racchiudeva un segreto, un segreto senza il quale sarebbe stato impossibile vivere»). È il cammino percorso da un intero popolo, di cui Solženicyn ha sempre avvertito la responsabilità di custodire la memoria e la coscienza, e insieme il suo stesso cammino personale, tracciato attraverso la figura del protagonista, Gleb Nerzin (lo stesso nome prenderà il protagonista nel successivo, maturo romanzo Il primo cerchio).

Ama la rivoluzione!, presentato alla Biblioteca Ambrosiana l’8 marzo scorso alla presenza di Ignat Solženicyn, uno dei figli dello scrittore, narra la vicenda di un giovane intellettuale sorpreso dallo scoppio della guerra nelle aule universitarie di Mosca, impaziente di combattere in prima linea per aggiudicare alla patria la vittoria finale e portare la rivoluzione in tutto il mondo, ma costretto – in quanto riformato alla visita medica – a una poco esaltante marcia verso le retrovie in un reparto di salmeria («il contingente degli invalidi»).

È un’opera profondamente autobiografica, scritta da Solženicyn nel 1948 mentre era internato in un campo di lavoro per scienziati, la saraska di Marfino, fortunosamente messa per iscritto (a differenza di altre opere dello stesso periodo, in particolare il poema La stradina, 8mila versi serbati per anni dall’autore nella memoria), e salvata da una coraggiosa funzionaria del lager che gliel’avrebbe restituita sei anni dopo. Un’opera in cui l’autore fissa il mutamento che sta avvenendo in lui, intellettuale comunista e brillante ufficiale arrestato durante la guerra, costretto dalle circostanze a rivedere tutte le proprie convinzioni.

L’ingloriosa marcia di Gleb, che cerca disperatamente, lungo tutta la narrazione, di mutarne la rotta per inseguire i suoi ideali, è in realtà il percorso della vita, che si incarica, per Nerzin come per Solzenicyn, di liberare l’intellettuale entusiasta, confidente nel «giovane paese dalla rossa bandiera», dalle sue utopistiche convinzioni. È un processo liberatorio che avviene secondo un duplice registro: il tribunale della storia e il tribunale della coscienza qui si uniscono per ricondurre la persona a se stessa. A questo conduce lo scontro di Nerzin con la burocrazia, la miopia e gli interessi individuali che soppiantano nel sistema i luminosi ideali del socialismo e, più in generale, ogni idea di giustizia e di bene comune («viveva e soffriva il tracollo sempre più evidente dell’Armata Rossa come la malattia mortale di un congiunto… A quale scopo vivere se ciò che di più luminoso era apparso nella storia dell’umanità veniva soffocato?»); a questo conduce il suo scontro con l’atrocità delle repressioni, della vita ai lavori forzati e in deportazione attraverso i racconti dei nuovi vicini di casa, i Diomidov, che squarciano un velo su una realtà apparentemente remota ma in realtà così prossima da sfiorare il protagonista e la moglie.

Read complete article in La Bussola Quotidiana

Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Address

A classic text from one of the greatest thinkers, writers and witness of the XXth Century.

A World Split Apart. Text of Address by Alexander Solzhenitsyn at Harvard Class Day Afternoon Exercises, Thursday, June 8, 1978.

here you can read about the background of the address in the Harvard Magazine