Hungarian Septic Services, Ideology and Human Dignity, by Bradley J. Birzer.

No one I know personally who knew Thomas Molnar (1921-2010) has ever said a kind word about his personality. If anything, he gained notoriety, even among those who respected him, through an infamy of intolerance, often under the unimaginative guise and excuse of “not suffering fools gladly.” This, in part, helps explain the lack of almost any notice of his death by the conservative world in 2010. He passed into the next world without—really—even a brief sigh or a fond fare well from this one. Few even offered a bitter fare well. Almost all seemed to have simply forgotten the man.

A recent google search reveals almost as many hits for a Thomas Molnar Septic Tank Service in South Bend as it does for the deceased Hungarian scholar. Yet, at one point, he served as a mainstay for both Commonweal and National Review.

Whatever his deficiencies in personality, no one could claim Molnar did not possess a rather expansive genius. Even a cursory examination of his publications—in terms of books as well as articles—overwhelms the would-be researcher. As with many of the greats of his generation, he wrote widely on a variety of topics and in a variety of fields on his heroes such as George Bernanos, educational theories, intellectualism, and the confluence of media and ideology.

His prolific output revivals that of Russell Kirk, a man who inspired, intrigued, and perplexed the Eastern European. Though the two walked across North Africa together in the summer of 1963, Molnar’s published travel memoir mentions Kirk only as an eccentric travel companion who attracted the attention of innumerable Arab and Berber children because of his outlandish appearance.

The Michiganian offered his own praise of Molnar far more openly, considering the Hungarian’s early book on the history of intellectuals, The Decline of the Intellectual, to be one of the most important works of the century.

A Christian Humanism of Sorts

Much of what Molnar wrote and argued during his adult life would fit nicely into the realm of possibilities for those admired at The Imaginative Conservative. Yet, he was always more of a European conservative than an American one. He might very well have been the model—if somewhat imagined on the Austrian’s part—conservative for Hayek’s 1957 famous Mont Pelerin Address, “Why I am Not a Conservative.”

From an American perspective, Molnar might fit better into the category of reactionary than conservative. Admittedly, such labels are as arbitrary as they are problematic. But, Molnar was a man who admired Charles Maurras and many of the Spaniards allied with Franco, but who also actively despised the National Socialists and found himself imprisoned in Dachau at the end of the Second World War. Molnar’s counterrevolutionary streak was as anti-ideological as it was curmudgeonly and, as John Zmirak has so effectively argued, always contrarian. In the end, Molnar believed the communists and the fascists of all stripes to share more in common than not, especially in their embrace of modernity and Gnosticism.

Whatever brief intellectual flirtations Molnar had with the extreme right of his youth, by the 1960s, Molnar had returned to his childhood faith and embraced an orthodox—if somewhat rigid—Roman Catholicism. Certainly, one could place Molnar into the category of Christian humanist, a title, role, and idea to which he gave much thought and spiritual assent. When assessing Molnar’s role in the twentieth century, we will miss his profundity as a thinker if we do not take this Christian humanism into account.

Utopia and the Ideologues

Of his many works, Molnar’s 1967 book, Utopia: The Perennial Heresy, published in the final days of the greatness of Sheed and Ward remains, perhaps, his most intriguing and relevant to today’s problems. In it, Molnar analyzed what he considered the never-ending temptation in this world, the belief that man can achieve perfection by his own will and ability and without God. Of course, Molnar offers nothing profound or original in this. Great writers and thinkers throughout the Judeo-Christian tradition had recognized the origins of perfectionism in the devil’s temptation in the Garden.

Unlike many others, though, especially those who describe the first temptation in the bible in passing, Molnar presents a very complex argument against it, noting that even the very thought of perfection is evil. Yet, because of the fall, man easily slides into such dangerous thinking.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

E il mito si fece carne. L’avventura di Russell Kirk, by Marco Respinti.

Il logos si è fatto carne, dice il Vangelo secondo san Giovanni. E quindi anche il mito è divenuto un fatto, glossa C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) in un breve, densissimo saggio del 1944, Myth Became Fact, che spiega perfettamente cosa intendesse J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) affermando: «Dio è il Signore, degli angeli, e degli uomini – e degli elfi. […] L’Evangelium non ha abrogato le leggende; le ha santificate, specialmente nel “lieto fine”» (Sulle fiabe, 1939); cosa intendesse Gilbert K. Chesterton (1874-1936) ‒ maestro di Lewis e di Tolkien ‒ parlando di “etica del paese delle fate” e addirittura paragonando il Magnificat alla fiaba di Cenerentola (Ortodossia, 1908); e cosa intendessero Chesterton e Lewis con “sacramentalizzazione dell’immaginazione” a proposito di George MacDonald (1824-1905), maestro loro e pure di Tolkien.

Ne tratta dottamente, proprio ragionando degli autori citati, il cardinal Christoph Schönborn ne Il Mistero dell’Incarnazione (Piemme, Milano 1989), un “vecchio”, prezioso libro tradotto dal tedesco dal padre gesuita Guido Sommavilla (1920-2007), massimo esperto di Romano Guardini, Franz Kafka, Friedrich Nietzsche, Fëdor M. Dostoevskij e guarda caso proprio Tolkien, quasi anticipando una sensibilità teologica, nutrita di potenti suggestioni letterarie, popolare oggi con Papa Francesco. Ebbene, uno degli ultimi epigoni di questo sposalizio tra filosofia e fantasia celebrato secondo il rito di santa romana Chiesa è il pensatore statunitense Russell Kirk (1918-1994), di cui ricorre oggi, 29 aprile, il ventennale della scomparsa.

Kirk è noto soprattutto come “padre” del conservatorismo americano del secondo Novecento, come neo-giusnaturalista cristiano alla scuola di Edmund Burke (1729-1797) e come apologeta antigiacobino della storia istituzionale americana. Ma nulla di tutta la sua riflessione “politica” (30 volumi, centinaia fra saggi e articoli) sarebbe venuto alla luce se egli non avesse sempre coltivato, con timore e tremore, il senso del mistero insito nella realtà umana.

Kirk è stato infatti anzitutto un cantore dell’irriducibilità dell’esperienza umana alla semplice materia (una delle sue citazioni preferite è di Burke, là dove lo statista anglo-irlandese descriveva così la spaccatura epocale introdotta dalla Rivoluzione Francese: «Ma l’era della cavalleria è finita. Le è succeduta quella dei sofisti, degli economisti e dei calcolatori, e la gloria d’Europa è estinta per sempre»), e proprio per questo un avversario lucido delle ideologie e delle ideocrazie.

Per Kirk la stoffa dell’avventura umana è il legame con il trascendente che la definisce e il bisogno religioso che la costituisce, da cui derivano quel senso del limite e quella vocazione comunitaria che sono le uniche coordinate di una politica a misura di uomo, e possibilmente, direbbe san Giovanni Paolo II (a cui, in punto di morte, è andato l’ultimo pensiero di Kirk), secondo il piano di Dio. Per questo il pensatore americano sospettava di tutte quelle ciclopiche costruzioni umane, fisiche e metafisiche, che altro non sono se non ennesime Babeli; come Chesterton, Kirk aveva imparato dalle metafore delle favole che i giganti vanno abbattuti proprio perché sono giganteschi, monumenti vani alla smisuratezza dell’orgoglio umano.

La famiglia in cui nacque aveva educato Kirk a una morale rigida e spartana, erede di un retaggio calvinista che strada facendo aveva però perso i tratti della vera spiritualità riducendosi a un codice. Efficace, ma estremamente limitato. Costretto a lungo alla solitudine, Kirk prese allora a confrontarsi con quei campioni dell’umano sentire che prima di lui, e meglio di lui, si erano trovati ad affrontare le stranezze, le difficoltà e le domande dell’esistenza. Maturò dunque dialogando con autori che nessuno leggeva più: Kirk l’ha definita una “conversione intellettuale”, ma è strano perché quell’etichetta lo irritava. Voleva solo dire che nessun fatto eclatante gli stravolse un giorno la vita; ma anche qui, intendiamoci. Le molte narrazioni della sua storia personale (scritte come romanzi non romanzati) mostrano bene come la “normalità” della sua vita sia sempre stata “straordinaria”. Come le vite di tutti. Come in una favola, una fiaba o un mito (direbbe il Tolkien che Kirk molto amava) che per di più hanno il supremo vantaggio di essere accaduti sul serio.

Kirk ha affrontato de visu il mistero dell’esistenza umana anzitutto come cantore dell’avventura “mitica” dell’uomo di fronte all’Assoluto (componendo così anche storie di paura e thriller metafisici tra i più belli di questo genere letterario) e in questo modo ha imparato l’umile saggezza di farsi seguace di chi, più avanti di lui lungo questo cammino, lo ha saputo trarre per mano dal mito alla storia. Due nomi su tutti, appositamente diversissimi: il “grande” T.S. Eliot (1898-1965) ‒ di cui fu prima discepolo, e poi amico e biografo ‒ e Annette, l’“attivista” cattolica che sposerà nel 1964, “piccola” parrebbe, ma enorme nel portarne a conclusione la conversione, avvenuta in quello stesso 1964 (mezzo secolo fa esatto).

Read the complete article in La Nuova Bussola Quotidiana

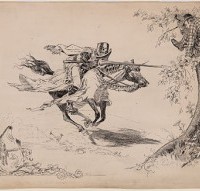

Mark Twain and Russell Kirk against the Machine

Though neither an humanist nor a Christian—nor, for that matter, even a romantic in the vein of Blake who feared the “dark Satanic mills” of Industrial England—Mark Twain identified the late-nineteenth century fear of the machine run amok perfectly in his last novel, the tragically whimsical A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. One of the first to use time travel as a plot device, the story revolves around Hank Morgan, an engineer devoid of any poetry or sentiment. As his German last name indicates, he is the man of “tomorrow.” A practical man schooled in the servile rather than the liberal arts, Morgan can create almost any type of mechanism: “guns, revolvers, cannon, boilers, engines, all sorts of labor-saving machinery.” A materialist, he “could make anything a body wanted—anything in the world, it didn’t make a difference what; and if there wasn’t any quick new-fangled way to make a thing, [he] could invent one.” He was also, Hank assures the reader, “full of fight.” And, a conflict employing crowbars with one of his employees, a man named Hercules, results in severe blow to Morgan’s head, knocking him unconscious.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative