Hungarian Septic Services, Ideology and Human Dignity, by Bradley J. Birzer.

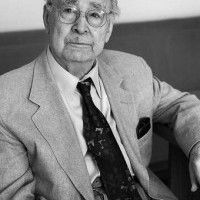

No one I know personally who knew Thomas Molnar (1921-2010) has ever said a kind word about his personality. If anything, he gained notoriety, even among those who respected him, through an infamy of intolerance, often under the unimaginative guise and excuse of “not suffering fools gladly.” This, in part, helps explain the lack of almost any notice of his death by the conservative world in 2010. He passed into the next world without—really—even a brief sigh or a fond fare well from this one. Few even offered a bitter fare well. Almost all seemed to have simply forgotten the man.

A recent google search reveals almost as many hits for a Thomas Molnar Septic Tank Service in South Bend as it does for the deceased Hungarian scholar. Yet, at one point, he served as a mainstay for both Commonweal and National Review.

Whatever his deficiencies in personality, no one could claim Molnar did not possess a rather expansive genius. Even a cursory examination of his publications—in terms of books as well as articles—overwhelms the would-be researcher. As with many of the greats of his generation, he wrote widely on a variety of topics and in a variety of fields on his heroes such as George Bernanos, educational theories, intellectualism, and the confluence of media and ideology.

His prolific output revivals that of Russell Kirk, a man who inspired, intrigued, and perplexed the Eastern European. Though the two walked across North Africa together in the summer of 1963, Molnar’s published travel memoir mentions Kirk only as an eccentric travel companion who attracted the attention of innumerable Arab and Berber children because of his outlandish appearance.

The Michiganian offered his own praise of Molnar far more openly, considering the Hungarian’s early book on the history of intellectuals, The Decline of the Intellectual, to be one of the most important works of the century.

A Christian Humanism of Sorts

Much of what Molnar wrote and argued during his adult life would fit nicely into the realm of possibilities for those admired at The Imaginative Conservative. Yet, he was always more of a European conservative than an American one. He might very well have been the model—if somewhat imagined on the Austrian’s part—conservative for Hayek’s 1957 famous Mont Pelerin Address, “Why I am Not a Conservative.”

From an American perspective, Molnar might fit better into the category of reactionary than conservative. Admittedly, such labels are as arbitrary as they are problematic. But, Molnar was a man who admired Charles Maurras and many of the Spaniards allied with Franco, but who also actively despised the National Socialists and found himself imprisoned in Dachau at the end of the Second World War. Molnar’s counterrevolutionary streak was as anti-ideological as it was curmudgeonly and, as John Zmirak has so effectively argued, always contrarian. In the end, Molnar believed the communists and the fascists of all stripes to share more in common than not, especially in their embrace of modernity and Gnosticism.

Whatever brief intellectual flirtations Molnar had with the extreme right of his youth, by the 1960s, Molnar had returned to his childhood faith and embraced an orthodox—if somewhat rigid—Roman Catholicism. Certainly, one could place Molnar into the category of Christian humanist, a title, role, and idea to which he gave much thought and spiritual assent. When assessing Molnar’s role in the twentieth century, we will miss his profundity as a thinker if we do not take this Christian humanism into account.

Utopia and the Ideologues

Of his many works, Molnar’s 1967 book, Utopia: The Perennial Heresy, published in the final days of the greatness of Sheed and Ward remains, perhaps, his most intriguing and relevant to today’s problems. In it, Molnar analyzed what he considered the never-ending temptation in this world, the belief that man can achieve perfection by his own will and ability and without God. Of course, Molnar offers nothing profound or original in this. Great writers and thinkers throughout the Judeo-Christian tradition had recognized the origins of perfectionism in the devil’s temptation in the Garden.

Unlike many others, though, especially those who describe the first temptation in the bible in passing, Molnar presents a very complex argument against it, noting that even the very thought of perfection is evil. Yet, because of the fall, man easily slides into such dangerous thinking.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative