Hungarian Septic Services, Ideology and Human Dignity, by Bradley J. Birzer.

No one I know personally who knew Thomas Molnar (1921-2010) has ever said a kind word about his personality. If anything, he gained notoriety, even among those who respected him, through an infamy of intolerance, often under the unimaginative guise and excuse of “not suffering fools gladly.” This, in part, helps explain the lack of almost any notice of his death by the conservative world in 2010. He passed into the next world without—really—even a brief sigh or a fond fare well from this one. Few even offered a bitter fare well. Almost all seemed to have simply forgotten the man.

A recent google search reveals almost as many hits for a Thomas Molnar Septic Tank Service in South Bend as it does for the deceased Hungarian scholar. Yet, at one point, he served as a mainstay for both Commonweal and National Review.

Whatever his deficiencies in personality, no one could claim Molnar did not possess a rather expansive genius. Even a cursory examination of his publications—in terms of books as well as articles—overwhelms the would-be researcher. As with many of the greats of his generation, he wrote widely on a variety of topics and in a variety of fields on his heroes such as George Bernanos, educational theories, intellectualism, and the confluence of media and ideology.

His prolific output revivals that of Russell Kirk, a man who inspired, intrigued, and perplexed the Eastern European. Though the two walked across North Africa together in the summer of 1963, Molnar’s published travel memoir mentions Kirk only as an eccentric travel companion who attracted the attention of innumerable Arab and Berber children because of his outlandish appearance.

The Michiganian offered his own praise of Molnar far more openly, considering the Hungarian’s early book on the history of intellectuals, The Decline of the Intellectual, to be one of the most important works of the century.

A Christian Humanism of Sorts

Much of what Molnar wrote and argued during his adult life would fit nicely into the realm of possibilities for those admired at The Imaginative Conservative. Yet, he was always more of a European conservative than an American one. He might very well have been the model—if somewhat imagined on the Austrian’s part—conservative for Hayek’s 1957 famous Mont Pelerin Address, “Why I am Not a Conservative.”

From an American perspective, Molnar might fit better into the category of reactionary than conservative. Admittedly, such labels are as arbitrary as they are problematic. But, Molnar was a man who admired Charles Maurras and many of the Spaniards allied with Franco, but who also actively despised the National Socialists and found himself imprisoned in Dachau at the end of the Second World War. Molnar’s counterrevolutionary streak was as anti-ideological as it was curmudgeonly and, as John Zmirak has so effectively argued, always contrarian. In the end, Molnar believed the communists and the fascists of all stripes to share more in common than not, especially in their embrace of modernity and Gnosticism.

Whatever brief intellectual flirtations Molnar had with the extreme right of his youth, by the 1960s, Molnar had returned to his childhood faith and embraced an orthodox—if somewhat rigid—Roman Catholicism. Certainly, one could place Molnar into the category of Christian humanist, a title, role, and idea to which he gave much thought and spiritual assent. When assessing Molnar’s role in the twentieth century, we will miss his profundity as a thinker if we do not take this Christian humanism into account.

Utopia and the Ideologues

Of his many works, Molnar’s 1967 book, Utopia: The Perennial Heresy, published in the final days of the greatness of Sheed and Ward remains, perhaps, his most intriguing and relevant to today’s problems. In it, Molnar analyzed what he considered the never-ending temptation in this world, the belief that man can achieve perfection by his own will and ability and without God. Of course, Molnar offers nothing profound or original in this. Great writers and thinkers throughout the Judeo-Christian tradition had recognized the origins of perfectionism in the devil’s temptation in the Garden.

Unlike many others, though, especially those who describe the first temptation in the bible in passing, Molnar presents a very complex argument against it, noting that even the very thought of perfection is evil. Yet, because of the fall, man easily slides into such dangerous thinking.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Eugenio Corti, il cantastorie del Regno, by Giulia Tanel

La sera di martedì 4 febbraio Eugenio Corti ha fatto ritorno al Padre. Classe 1921, lo scrittore aveva conformato la sua vita al versetto del Padre Nostro che recita “Venga il Tuo Regno”, combattendo la buona battaglia tramite la scrittura.

Uomo dal portamento distinto e dal fare pacato ma anche caparbio, Corti scrutava con i suoi attenti occhi azzurri i tanti lettori, molto spesso giovani, che si recavano a trovarlo nella sua casa in Brianza. Personalmente ricordo il suo atteggiamento vigoroso e paterno, dettato e supportato dalle decisive esperienze maturate durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale e da una fede granitica. Dialogando con lui si aveva la percezione di essere di fronte a un maestro da cui attingere preziose considerazioni sul passato e sull’epoca contemporanea; nel contempo, emergeva anche la consapevolezza di essere in presenza di una persona cui – da cattolici – guardare come modello di comportamento, perché lo sguardo di Corti, benché permeato di un sano realismo, era sempre orientato a Dio.

Non a caso, accanto all’età d’oro greca, il periodo storico più amato dallo scrittore brianteo era il Medioevo, ossia l’epoca in cui il messaggio cristiano si è diffuso in maniera capillare ed è diventato un fenomeno ‘di popolo’, dando luogo alla Res Publica Christiana. In quei secoli, troppo spesso classificati come ‘bui’ e invece ricchissimi sotto diversi aspetti, ogni ambito del vivere quotidiano era orientato – seppur con le dovute eccezioni – agli ideali del Vangelo: dal modo di concepire la guerra e la cavalleria, allo sviluppo dell’arte pittorica e architettonica, al ruolo assegnato alle donne… E proprio riguardo quest’ultimo aspetto, entrando nella casa di Corti si rimaneva piacevolmente colpiti dalla presenza riservata, ma assolutamente rilevante, di sua moglie Vanda, che lo scrittore contemplava ancora con sguardo innamorato e riconoscente, nonostante fossero sposati dal 1951.

Ma si diceva della centralità della fede nella vita e nel pensiero di Corti, la quale trova conferma anche nei suoi articoli e nei libri – molto vari per genere e argomento – ch’egli ha scritto dal 1947 in avanti. Tra questi spicca per importanza il romanzo storico Il Cavallo Rosso (Edizioni Ares, 1983), oramai giunto alla ventinovesima edizione e tradotto in otto lingue. Questo testo – che ha richiesto a Corti ben undici anni di lavoro – narra le vicende di alcuni ragazzi della Brianza e del loro incontro con il mondo esterno, sullo sfondo dei grandi avvenimenti storici succedutisi in Italia e nel mondo tra il 1940, anno dell’entrata in guerra dell’Italia, e il 1974, anno del referendum sul divorzio. Scorrendo pagina dopo pagina, moltissimi lettori sono rimasti avvinti nella narrazione e – oltre ad aver potuto rivivere quasi in presa diretta gli anni del secondo conflitto mondiale e della ricostruzione – hanno avuto modo di apprezzare le riflessioni storiche, teologiche e teleologiche che Corti non mancava mai di inserire nei propri scritti, in forma più o meno diretta.

Un’altra opera fondamentale lasciataci dallo scrittore brianteo è Il fumo nel Tempio (Edizioni Ares, 1996), una raccolta di articoli scritti dal 1970 in poi sulla difficile situazione della Chiesa nel post Concilio, sulla perdita di valori della società, sulla crisi della politica e in particolare della Democrazia Cristiana e, infine, sull’egemonia di una cultura di matrice laica e troppo spesso ideologizzata. Sono testi di una lucidità spesso disarmante, propria di un osservatore attento e onesto qual era Corti, convinto che il parametro di giudizio cui fare riferimento è sempre l’insegnamento di Cristo, perché solo in questo modo è possibile vivere in pienezza e gustare anche in terra un imperfetto assaggio di felicità e di Bellezza.

Sintomatica di quest’approccio alla vita è la risposta data da Corti alla domanda su quale fosse la cosa più bella che gli sia mai accaduta: «L’essere venuto al mondo, sicuramente. La prova è stata anche dura, come per tutti. Ma è stato l’esistere, l’essere, che mi ha aperto tutte le altre porte. Anche quella della consolante Speranza cristiana in una felicità intramontabile in Dio, dopo la morte terrena».

Al termine di una vita intensa e luminosa, la poesia posta da Eugenio Corti in calce alle 1274 pagine che compongono Il Cavallo Rosso appare quasi come un suo testamento: “Ecco, ora svaniscono, / i volti e i luoghi, con quella parte di noi che, come poteva, / li amava, / Per rinnovarsi, trasfigurati, in un’altra trama” (T.S. Eliot). Requiescat in pace!

Published in La nuova bussola quotidiana

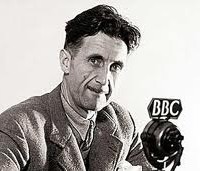

George Orwell’s Despair, by Russell Kirk.

In the twentieth century, no novelist exerted a stronger influence upon political opinion, in Britain and America, than did George Orwell. Also Orwell was the most telling writer about poverty. In a strange and desperate way, Orwell was a lover of the permanent things. Yet because he could discern no source of abiding justice and love in the universe, Orwell found this life of ours not worth living. In his sardonic fashion, nevertheless, he struck some fierce blows at abnormality in politics and literature.

“There is no such thing as genuinely nonpolitical literature,” Orwell wrote in his essay on “The Prevention of Literature” (1945), “and least of all in an age like our own, when fears, hatreds, and loyalties of a directly political kind are near to the surface of everyone’s consciousness….It follows that the atmosphere of totalitarianism is deadly to any kind of prose writer, though a poet, at any rate a lyric poet, might possibly find it breathable. And in any totalitarian society that survives for more than a couple of generations, it is probable that prose literature, of the kind that has existed during the past four hundred years, must actually come to an end.” Soviet Russia supplies the proof: “It is true that literary prostitutes like Ilya Ehrenberg or Alexei Tolstoy are paid huge sums of money, but the only thing which is of any value to the writer as such—his freedom of expression—is taken away from him.”

read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative