Tintin: The True European, by Peter Strzelecki Rieth

As Europe struggles with economic woes brought on by the combination of unrestricted government largess and corruption and avarice, it seems every thread of this current struggle emanates from the problem of European character and the concurrent angst surrounding it. A brief reflection on the problem of European character and an illustration of how centered it is at the causal crux of the European crisis may equip us to provide some solutions.

In brief, what I call the problem of European character and the concurrent angst surrounding it is the fact that the essence of the European Union, the modern European political project, is a negation of war between European nations. This means that the European character, if one can even speak of such a thing, is founded in the proposition that whatever happens, Europeans must remain united, for division inevitably leads to a war of all against all and the annihilation of European civilization. The founding event of this outlook was World War II. As such, there is no positive defining trait of European character, only a negation of war, which is to say that modern Europe is founded on the fear of being toward death. This special kind of glue holding the Union together is, to my mind, best defined using Heidegger’s concept of angst. Thus, when crisis strikes on account of numerous errors, a fear sets in against tampering with the ailing union as that may lead to its collapse and to war. Yet to do nothing, or as some quarters are urging, to strengthen the faulty bonds of union even further, will lead also to collapse and war because it will deepen the crisis and give rise to public aggravation and revolutionary fervor. The diagnosis is clear: the European Union, which arose from the common European character trait of angst, cannot sustain itself by angst. The European character must be enriched with positive traits or be undone.

Some “Euro-enthusiasts” may well now shake their heads and claim that this expanded, positive European character already exists, made visible in the thousands of pages of regulations instructing the citizenry on how to be tolerant, open-minded humanitarians who love mother Earth, their fellow man, and embrace science. The chief problem with this view, abstracting from the philosophical questions that arise regarding the desirability of this particular modern, ahistorical, and secular European character, is that it resides in regulations, not in the heart of the people. Regulation lacks the personal import even of law. The importance of this distinction is such that regulation dictates the minutiae of everyday life. It not only prescribes an ethos, as law does, it dictates the precise, quantified application of said ethos. Civilizations which are built on virtues, whether piety or tolerance, that are mandated, registered, stamped, and stipulated in paragraph 16, subsection 2 of the revised revision of the regulations revising previous revisions–such civilizations die.

Here, angst will worry: does it therefore follow that Europeans are destined to fall back on national and ethnic prejudices? Perhaps there are other alternatives available to them besides secular, liberal sophistication masking bureaucratic banality or some pompous nationalist stereotypes. Certainly the philosophers present us with numerous alternatives, though all of them might well be impractical for any landmass not populated by a majority of philosophers. We also cannot, it appears to me, reach far back into European history, for to expect of modern Europeans to adopt Roman virtue, Athenian wisdom, let alone Christian agape, may well be expecting too much. If we wish to look for something in modern European history grounded in a firmer basis than philosophical speculation then I suggest we look no further than Tintin.

Tintin, for those who do not know and love him, is the European par excellence, created by author Hergé. His authority is widely acknowledged by children throughout the world, regardless of their age. General DeGaulle apparently called Tintin his only international rival. Tintin, if one really thinks about it, is the perfect template for a European character rooted in positive traits rather than merely in angst. Rather menacingly, the present generation risks knowing Tintin not through his European manifestation, but through the rather poor interpretation of his adventures presented to the world by the American director Steven Spielberg. All the more reason why I shall now endeavor to make a composite defense of Tintin as being of paramount importance and relevance to the present crisis.

First, Tintin has proven himself a keen political realist. I begin with this because some may well now expect me to embark on platitudes regarding Boy Scout virtues as exemplified by Tintin, rather than say anything of hard-nosed relevance to the grave situation Europe faces. Quite the contrary! It was Tintin, who, back in 1929, exposed the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union and the plight of its people at a time when the vast majority of Western opinion was either ignorant of or fascinated with the Soviet system. Tintin’s revelations were, for decades, characterized as childish caricatures until the publication of the Black Book of Communism made the broad public aware of what Tintin had reported as fact from the very outset. This, if nothing else, qualifies Tintin for serious consideration as a relevant voice in European affairs: where so many were wrong about the Soviet Union, he was right from the beginning.

Detractors will no doubt point out that Tintin may well have been stunningly right in his premiere journalism, but quickly followed up on that by being stunningly wrong in his treatment of European colonialism. From his wholesale slaughter of the helpless species populating the Congo, to his insensitive remarks to a room full of Congolese regarding their homeland “Belgium”, one quickly can see why these detractors may feel it quite a bad idea to hold Tintin up as a worthy ideal for European character. Why, at one point, Tintin even helped a Priest!

Yet the measure of ideals is not their perfection, but rather how they deal with their all too human imperfections. In the case of young Tintin in Congo, he did what he could to help the native populations, while everything we might be tempted to fault him for was, as author Hergé admitted, the result of not taking his work too seriously at the time and being unreflective about the prejudices of his age. Out of all of Tintin’s remarkable adventures, his sojourn through the Congo may be most fraught with vices, but we can take heart that Tintin learned from his mistakes, as we can see in his escapades in the Far East shortly after leaving the Congo. There, Tintin so exemplified courageous virtues in his gallant struggle to aid the Chinese in their time of desperation as to have earned the praise of Chiang Kai-Shek himself, not to mention endearing himself to the Dalai Lama, who to this day declares his love for the boy reporter.

This evolution from a rhino-hunting, crocodile-dynamiting, Al Capone-chasing adventurer into a serious young man of high moral principle and gallant instinct betrays a character trait sorely lacking in the modern European. The modern European is nihilistic in private, bureaucratic in public. Tintin, by contrast, demonstrated a a playful lightness and joi de vivre in his private life combined with moral conscience in public life. Tintin’s youth, his evolution, is not linear, but rather curvilinear. In the beginning, he fluctuates between noble deeds like helping the Indians by fighting exploitative Americans and lighthearted slap stick. Yet as Tintin’s experience of the world grows, his moral imagination is refined and his humor matures. The latter is actually tied intimately with the former, as moral reflection is quite impossible without humor. Only a character type like that of Tintin’s could permit such an evolution, and only a European of such character could hope to escape the trap of modern European Union: the prospect of despotic union or war, both laced with angst.

Tintin’s political teaching does not, however, stop there. He provides us with a wonderful illustration of the folly of radical factionalism and demonstrates how it is always the mother of despotism. How memorable his misadventures are in the banana republic of Generals Alcazar and Tapioca, where revolutions take place on a daily basis, where the people oscillate between wild revolutionary fervor and grinding tyranny, where no matter who wins, dictatorship and poverty remain constant. The illustration, although set in a South American context, certainly does tell us quite a bit about human nature and the folly of revolutions. Far from being a means towards salvation from tyranny, Tintin seems to teach us that strife, faction, and partisan division are a direct route to tyranny. Civilized people, in contrast to the banana republics, Tintin suggests, never engage in revolution but rather rely on other means. Revolutions appear an easy solution, but end up solving nothing while expending the accumulated public stock of disappointed hope.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Anders Breivik: après le sang, par Joël Prieur

Nous sommes le 22 juillet 2011 en Norvège : deux actions ont lieu le même jour. Deux faits divers mais tragiques : l’explosion d’une bombe de 1100 kg au cœur de la Ville d’Oslo. Huit morts mais on n’a pas encore fini, aujourd’hui, de relever les ruines produites par l’explosion ; puis une fusillade dans l’île d’Utoya, où avait lieu la traditionnelle Université d’été des jeunes travaillistes : 69 morts. C’est le plus important massacre opéré par un seul homme. Son nom ? Anders Breivik.

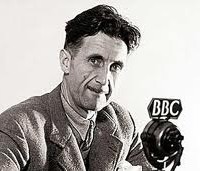

George Orwell’s Despair, by Russell Kirk.

In the twentieth century, no novelist exerted a stronger influence upon political opinion, in Britain and America, than did George Orwell. Also Orwell was the most telling writer about poverty. In a strange and desperate way, Orwell was a lover of the permanent things. Yet because he could discern no source of abiding justice and love in the universe, Orwell found this life of ours not worth living. In his sardonic fashion, nevertheless, he struck some fierce blows at abnormality in politics and literature.

“There is no such thing as genuinely nonpolitical literature,” Orwell wrote in his essay on “The Prevention of Literature” (1945), “and least of all in an age like our own, when fears, hatreds, and loyalties of a directly political kind are near to the surface of everyone’s consciousness….It follows that the atmosphere of totalitarianism is deadly to any kind of prose writer, though a poet, at any rate a lyric poet, might possibly find it breathable. And in any totalitarian society that survives for more than a couple of generations, it is probable that prose literature, of the kind that has existed during the past four hundred years, must actually come to an end.” Soviet Russia supplies the proof: “It is true that literary prostitutes like Ilya Ehrenberg or Alexei Tolstoy are paid huge sums of money, but the only thing which is of any value to the writer as such—his freedom of expression—is taken away from him.”

read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

The Christian Humanism of Willa Cather, by Bradley J. Birzer

On Sunday, August 11, 2013, my family and I began our now-yearly odyssey into the West. As I write this, our vacation is ending, and I’m typing this from the second floor of a rented house in the Rockies, looking across my laptop out the window at Mt. Ouray.

In two days, our kids have pre-opening at their academy, back in Michigan, and the next morning I’ll attend the same for my job. I’m not quite ready to leave the glories of the American West, but, should I continue to care about a steady income and providing for my family, eastward I must return.

Some of my very first posts at The Imaginative Conservative were written three years ago on such a trek. I can no longer embark on annual trips without thinking of The Imaginative Conservative and without considering editorial mastermind Winston Elliott’s birthday (August 13), a day that will be celebrated some day in the Republic of Texas and, if it still exists, the United States of America.

A significant part of our yearly ritual and travel is my wife reading fiction to me as I drive. Dedra has one of the best reading voices I’ve ever encountered, and, as long as my children aren’t fighting with one another or with imaginary friends, I look forward to her reading almost as much as I look forward to the sites I’m about to encounter on our adventures.

Dedra can read anything and read it well, but she most often gravitates either to the mysteries of Ralph McInerny and Sharon McCrumb or to the fiction of Willa Cather. We both have adored Cather since college. With The Imaginative Conservative’s beloved John Willson, I try to read Death Comes for the Archbishop at least once year. I think a solid case could be argued for considering this novel the “Great American Novel” if such a label needs to be employed. Cather’s West is what the American West should’ve been, rather than what it was. In Cather’s vision, the West is humane, challenging, and, ultimately, in the best Ciceronian sense, cosmopolitan.

Cather’s life

Looking back a century and a half, it would probably not have been wise to have bet on the success of Cather. Born in Virginia, her parents moved her to extreme south central Nebraska (only miles from the Kansas line and only about fifteen miles from the geographic center of the 48 states). Oldest of seven children, her parents homeschooled (or its past equivalent) Willa with their neighbors, raising her around German, Polish, Bohemian, Moravian, Swedish, and Russian immigrants. American Indians arrived in Red Cloud from time to time, as did Americans of African descent. All of this immigration and community with the treeless backdrop of the Great Plains fascinated Cather. Here, as a young woman, she experienced what most sociologists only imagine in their wildest dreams. While the various peoples and peopling of the land mattered to Cather, so too did the land.

Then the Genius of the Divide, the great, free spirit which breathes across it, must have bent lower than it ever bent to a human will before. The history of every country begins in the heart of a man or a woman.

So wrote Cather of her first great heroine, Alexandra, in O Pioneers!.

Graduating from the University of Nebraska in Lincoln in 1895, Cather went east to work as a muck-racking journalist. She gained considerable attention and fame at the notorious but popular McClures and she gave herself fulltime to her fiction in 1912. Her many works include: April Twilights (1903); Alexander’s Bridge (1912); O Pioneers! (1913); The Song of the Lark (1915); My Ántonia (1918); Youth and the Bright Medusa (1920); One of Ours (1922; for which she won the Pulitizer Prize); A Lost Lady (1923); The Professor’s House (1925); My Mortal Enemy (1926); Death Comes to the Archbishop (1927); Shadows on the Rock (1931); Obscure Destinies (1932); and Lucy Gayheart (1935).

Sometime in the 1920s, Cather’s anti-progressive views became quite clear, and the left despised her. She died, horribly, in some literary obscurity, rescued only after her death.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Overpopulation: Mother of all myths, by Jeb Blackwood

The world’s population is declining.

Those are fighting words in most circles but it’s the truth, and it’s occurring right before our eyes.

How can that be when in 2012 the US Census Bureau estimated the world population at 7 billion? That’s a lot of zeros! Well, the proof is in the statistics.

Let’s begin with what we know about fertility rate. To achieve perfect replacement, humans must have 2.13 children per woman. Some women have more children while others have fewer, but 2.13 is the magic number to maintain steady population. More than 90 countries (the USA and Canada among them) are currently experiencing a birthrate under that magic number . People are simply not having children.

And when we look at the 2009 United Nations documentation, “World Population Prospects” (yes, THE United Nations), the outlook appears grim. Not only do all six countries included on the chart show a marked birthrate decline over the last 60 years, but they all drop below the sustainability rate of 2.13 children per woman.

Pay close attention to the countries on the chart: the United States, Japan, Germany, France, Italy and Britain. All are world powers, and provide economic stability in their regions and to the world. So what if people stop having children? What difference does it make? There is a strong correlation between economic downturn and declining fertility rates.

read the complete article in Intercollegiate Review