E il mito si fece carne. L’avventura di Russell Kirk, by Marco Respinti.

Il logos si è fatto carne, dice il Vangelo secondo san Giovanni. E quindi anche il mito è divenuto un fatto, glossa C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) in un breve, densissimo saggio del 1944, Myth Became Fact, che spiega perfettamente cosa intendesse J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) affermando: «Dio è il Signore, degli angeli, e degli uomini – e degli elfi. […] L’Evangelium non ha abrogato le leggende; le ha santificate, specialmente nel “lieto fine”» (Sulle fiabe, 1939); cosa intendesse Gilbert K. Chesterton (1874-1936) ‒ maestro di Lewis e di Tolkien ‒ parlando di “etica del paese delle fate” e addirittura paragonando il Magnificat alla fiaba di Cenerentola (Ortodossia, 1908); e cosa intendessero Chesterton e Lewis con “sacramentalizzazione dell’immaginazione” a proposito di George MacDonald (1824-1905), maestro loro e pure di Tolkien.

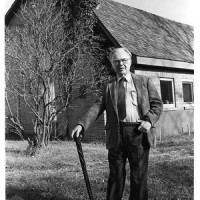

Ne tratta dottamente, proprio ragionando degli autori citati, il cardinal Christoph Schönborn ne Il Mistero dell’Incarnazione (Piemme, Milano 1989), un “vecchio”, prezioso libro tradotto dal tedesco dal padre gesuita Guido Sommavilla (1920-2007), massimo esperto di Romano Guardini, Franz Kafka, Friedrich Nietzsche, Fëdor M. Dostoevskij e guarda caso proprio Tolkien, quasi anticipando una sensibilità teologica, nutrita di potenti suggestioni letterarie, popolare oggi con Papa Francesco. Ebbene, uno degli ultimi epigoni di questo sposalizio tra filosofia e fantasia celebrato secondo il rito di santa romana Chiesa è il pensatore statunitense Russell Kirk (1918-1994), di cui ricorre oggi, 29 aprile, il ventennale della scomparsa.

Kirk è noto soprattutto come “padre” del conservatorismo americano del secondo Novecento, come neo-giusnaturalista cristiano alla scuola di Edmund Burke (1729-1797) e come apologeta antigiacobino della storia istituzionale americana. Ma nulla di tutta la sua riflessione “politica” (30 volumi, centinaia fra saggi e articoli) sarebbe venuto alla luce se egli non avesse sempre coltivato, con timore e tremore, il senso del mistero insito nella realtà umana.

Kirk è stato infatti anzitutto un cantore dell’irriducibilità dell’esperienza umana alla semplice materia (una delle sue citazioni preferite è di Burke, là dove lo statista anglo-irlandese descriveva così la spaccatura epocale introdotta dalla Rivoluzione Francese: «Ma l’era della cavalleria è finita. Le è succeduta quella dei sofisti, degli economisti e dei calcolatori, e la gloria d’Europa è estinta per sempre»), e proprio per questo un avversario lucido delle ideologie e delle ideocrazie.

Per Kirk la stoffa dell’avventura umana è il legame con il trascendente che la definisce e il bisogno religioso che la costituisce, da cui derivano quel senso del limite e quella vocazione comunitaria che sono le uniche coordinate di una politica a misura di uomo, e possibilmente, direbbe san Giovanni Paolo II (a cui, in punto di morte, è andato l’ultimo pensiero di Kirk), secondo il piano di Dio. Per questo il pensatore americano sospettava di tutte quelle ciclopiche costruzioni umane, fisiche e metafisiche, che altro non sono se non ennesime Babeli; come Chesterton, Kirk aveva imparato dalle metafore delle favole che i giganti vanno abbattuti proprio perché sono giganteschi, monumenti vani alla smisuratezza dell’orgoglio umano.

La famiglia in cui nacque aveva educato Kirk a una morale rigida e spartana, erede di un retaggio calvinista che strada facendo aveva però perso i tratti della vera spiritualità riducendosi a un codice. Efficace, ma estremamente limitato. Costretto a lungo alla solitudine, Kirk prese allora a confrontarsi con quei campioni dell’umano sentire che prima di lui, e meglio di lui, si erano trovati ad affrontare le stranezze, le difficoltà e le domande dell’esistenza. Maturò dunque dialogando con autori che nessuno leggeva più: Kirk l’ha definita una “conversione intellettuale”, ma è strano perché quell’etichetta lo irritava. Voleva solo dire che nessun fatto eclatante gli stravolse un giorno la vita; ma anche qui, intendiamoci. Le molte narrazioni della sua storia personale (scritte come romanzi non romanzati) mostrano bene come la “normalità” della sua vita sia sempre stata “straordinaria”. Come le vite di tutti. Come in una favola, una fiaba o un mito (direbbe il Tolkien che Kirk molto amava) che per di più hanno il supremo vantaggio di essere accaduti sul serio.

Kirk ha affrontato de visu il mistero dell’esistenza umana anzitutto come cantore dell’avventura “mitica” dell’uomo di fronte all’Assoluto (componendo così anche storie di paura e thriller metafisici tra i più belli di questo genere letterario) e in questo modo ha imparato l’umile saggezza di farsi seguace di chi, più avanti di lui lungo questo cammino, lo ha saputo trarre per mano dal mito alla storia. Due nomi su tutti, appositamente diversissimi: il “grande” T.S. Eliot (1898-1965) ‒ di cui fu prima discepolo, e poi amico e biografo ‒ e Annette, l’“attivista” cattolica che sposerà nel 1964, “piccola” parrebbe, ma enorme nel portarne a conclusione la conversione, avvenuta in quello stesso 1964 (mezzo secolo fa esatto).

Read the complete article in La Nuova Bussola Quotidiana

A Scottish Remembrance of Russell Kirk, by Alvino-Mario Fantini

The Conservative Mind‘s author taught generations to re-enchant the world.

As an undergraduate, my first encounters with Professor Jeff Hart and The Dartmouth Review eventually led to my discovery of the works of Russell Kirk. Like William F. Buckley Jr., Kirk wrote about the need to raise, as historian George Nash put it, a “full-scale challenge to modernity”—in the arts, literature, religion, and politics. While both Buckley and Kirk enchanted me with their obvious love of language and mastery of words, it was Kirk who also managed to stir my spirit with an affection, kindness, and warmth that I did not find elsewhere. Here was a gentle, conservative aesthete.

But I’m not the only one who was affected in such a way by Kirk. And last year, to mark the 60th anniversary of the publication of his most famous work, The Conservative Mind, there were several tributes. Last summer, The University Bookman, which Kirk founded in 1960, published an on-line symposium discussing the book. In July, the Liberty Fund also published a tribute, along with three excellent rejoinders. In September, two more events took place: Lee Edwards at the Heritage Foundation hosted a panel with Matthew Spalding, Yuval Levin, and Peter Wehner to discuss the book’s impact; and a few days later, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, The Imaginative Conservative, and the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal co-sponsored a one-day seminar at Houston Baptist University.

Scottish Celebrations

One of the more interesting commemorations took place October 18-20 in Scotland, where a distinguished group of students and academics joined members of the Kirk family and their close friends at the University of St. Andrews to discuss The Conservative Mind—and to remember, in Willmoore Kendall’s words, the “benevolent sage of Mecosta”.

Some people aren’t aware that Kirk was a doctoral student at the University of St. Andrews; in fact, he remains the only American to have received a Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) from that esteemed university. His dissertation, titled “The Conservative’s Rout”—later re-named The Conservative Mind in discussions with publisher Henry Regnery—is still on file at the university, and the anniversary celebrations in Scotland began, appropriately enough, with a viewing of the original dissertation on Friday afternoon.

Attending the weekend’s events were a dozen or so promising young Americans, all current or former Wilbur Fellows who, after working for Russell and Annette Kirk, went on to study at St. Andrews. It was impressive to hear the deep affection with which each of them spoke about the Kirks—and about the time they spent at his ancestral home at Piety Hill.

Various Europeans also joined the celebrations—for, despite his focus on an ‘Anglo-American’ political tradition, many of Kirk’s published works are known across Continental Europe. Some have even been translated into Spanish, German, and Italian, and his ideas have influenced a range of European scholars. In Germany, Kirk’s contributions as a ‘conservative man of letters’ were recognized as so important, that he merited a lengthy entry (and photograph) in the Lexikon des Konservatismus (Dictionary of Conservatism), a 1996 work edited by the German noble, Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. Today even young members of Sweden’sKonservativt Forum are wont to quote Kirk approvingly.

The always charming and energetic Annette Kirk was also present in Scotland, along with two of her daughters and their families. On Friday evening, she hosted a private reception and dinner at the cliff-side Russell Hotel, where guests were treated to a talk by André Gushurst-Moore, currently Director of Pastoral Care at Downside School, an institution attached to the Benedictine Downside Abbey in Somerset, England.

Gushurst-Moore elaborated on some of the principal themes in Kirk’s works, speaking of Kirk’s defense of humane learning, the moral imagination, and “the permanent things.” Not coincidentally, these are precisely the themes closest to Gushurst-Moore’s own work. In his recent The Common Mind: Politics, Society and Christian Humanism from Thomas More to Russell Kirk (published in 2013 by Angelico Press), he profiles 12 great ‘Christian Humanists’ through the centuries, including Thomas More, Dr. Johnson, Edmund Burke, Orestes Brownson, and Russell Kirk, among others.

His was an eloquent and respectful tribute, which many found quite moving. It was a testament of sorts to the impact that Kirk’s writings—and his gentle character—had on people. And nearly two decades after his death, Kirk continues to touch people with the evocative power of his words (the late Frederick Wilhelmsen said “Kirk was essentially a poet who wrote in prose”). What a reminder of those T.S. Eliot lines from Four Quartets which Kirk was so fond of quoting: “the communication / Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.”

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

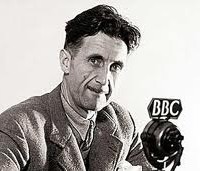

George Orwell’s Despair, by Russell Kirk.

In the twentieth century, no novelist exerted a stronger influence upon political opinion, in Britain and America, than did George Orwell. Also Orwell was the most telling writer about poverty. In a strange and desperate way, Orwell was a lover of the permanent things. Yet because he could discern no source of abiding justice and love in the universe, Orwell found this life of ours not worth living. In his sardonic fashion, nevertheless, he struck some fierce blows at abnormality in politics and literature.

“There is no such thing as genuinely nonpolitical literature,” Orwell wrote in his essay on “The Prevention of Literature” (1945), “and least of all in an age like our own, when fears, hatreds, and loyalties of a directly political kind are near to the surface of everyone’s consciousness….It follows that the atmosphere of totalitarianism is deadly to any kind of prose writer, though a poet, at any rate a lyric poet, might possibly find it breathable. And in any totalitarian society that survives for more than a couple of generations, it is probable that prose literature, of the kind that has existed during the past four hundred years, must actually come to an end.” Soviet Russia supplies the proof: “It is true that literary prostitutes like Ilya Ehrenberg or Alexei Tolstoy are paid huge sums of money, but the only thing which is of any value to the writer as such—his freedom of expression—is taken away from him.”

read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Russell Kirk Defends Assassination with Natural Law Theory, by Bradley J. Birzer

Therefore a little knot of brave and conscientious men determined to save Germany and Europe by killing Hitler…

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Mark Twain and Russell Kirk against the Machine

Though neither an humanist nor a Christian—nor, for that matter, even a romantic in the vein of Blake who feared the “dark Satanic mills” of Industrial England—Mark Twain identified the late-nineteenth century fear of the machine run amok perfectly in his last novel, the tragically whimsical A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. One of the first to use time travel as a plot device, the story revolves around Hank Morgan, an engineer devoid of any poetry or sentiment. As his German last name indicates, he is the man of “tomorrow.” A practical man schooled in the servile rather than the liberal arts, Morgan can create almost any type of mechanism: “guns, revolvers, cannon, boilers, engines, all sorts of labor-saving machinery.” A materialist, he “could make anything a body wanted—anything in the world, it didn’t make a difference what; and if there wasn’t any quick new-fangled way to make a thing, [he] could invent one.” He was also, Hank assures the reader, “full of fight.” And, a conflict employing crowbars with one of his employees, a man named Hercules, results in severe blow to Morgan’s head, knocking him unconscious.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative