Christopher Dawson: The Twofold Nature of Christian History, by Gerald J. Russello

For the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation is not simply a theophany—a revelation of God to Man; it is a new creation—the introduction of a new spiritual principle which gradually leavens and transforms human nature into something new. The history of the human race hinges on this unique divine event which gives meaning to the whole historical process.

Frodo versus Robespierre, by Joseph Pearce

The Persistence of History, by P. Bracy Bersnak

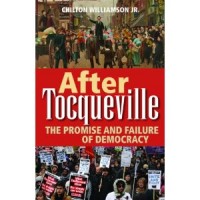

Twenty years ago, as the Cold War ended with the triumph of the West over Communism, Francis Fukuyama proclaimed the “end of history,” by which he meant that human political community had reached its final and best stage of development in the form of liberal democracy. Samuel Huntington spoke of a third great wave of democracy sweeping through eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia. But many of the new democracies were short lived, pulled down in an authoritarian undertow. History had a future after all.

Whether or not they agree with the specifics of Fukuyama’s claims, political scientists, policy analysts, and policy makers share his fundamental assumptions. They disagree chiefly over the means by which liberal democracy should be spread throughout the world. Though the experiences of the last decade have chastened advocates of promoting democracy around the world, support for liberal democracy remains the default position for U.S. foreign policy. Even when support for democracy undermines allies and facilitates the rise to power of anti-Western parties—that is, even when it seems to work contrary to the national interest—American administrations tend to stay faithful to promoting democracy.

That may be why Chilton Williamson, Jr. inclines toward defining democracy as a kind of religion. Williamson is a former literary editor of National Review, currently senior editor of Chronicles, and the author of several novels. He says that there is no generally accepted definition of democracy, and does not try to formulate one of his own, but seems to settle on characterizing it as a false religion that believes that the popular will should always prevail in government (pp. 73–74). If Williamson is right, his definition would go some way toward explaining why so many are blind to the weaknesses of contemporary democracy and the possibility of its demise: the inevitability and permanence of democracy is an article of faith.

The first part of Williamson’s book traces the history of modern democracy from American independence up to the present, focusing on the U.S. and Britain. He believes that democracies have best flourished in periods during which they were imperfectly democratic. Both American and British democracy experienced their golden ages when the franchise was broad but not universal, and when educated men of property played the leading roles in political life. By the late nineteenth century, this “aristocratic balance” was lost. During World War I governments mobilized their entire populations to fight and extended democracy more broadly than ever before. The war discredited European liberalism, which was blamed for the war and the weaknesses of multiethnic regimes that emerged from it. But the war did not discredit the democratic principle, which was pressed into the service of nationalism and socialism. It was only after World War II and the defeat of totalitarian National Socialism that liberal democracy was wholeheartedly embraced by peoples and governments. Until then, intellectuals were for the most part opposed to democracy. Men of letters as various as Stendahl, Matthew Arnold, Albert Camus, and T. S. Eliot expressed deep skepticism toward democracy. As Wyndham Lewis said, “No artist can ever love democracy.”

Williamson admires what Alfred Kahan called the aristocratic liberalism of Alexis de Tocqueville and others because they believed in popular government but were aware of its potential to threaten individual liberty, intellectual excellence, and the social bodies that make up civil society. While progressives of various stripes have sought to extend the principles of democracy from the political realm into civil society, conservatives have opposed this extension, believing with Tocqueville that nondemocratic social bodies in civil society counteracted dangerous tendencies in democratic politics. Williamson says that “it was in his fears, perhaps even more than in his hopes, that the author of Democracy in America proved himself to be a man of deep intuition and a true prophet of history” (p. 40). But Tocqueville is more a point of departure than an interlocutor for Williamson because democracy has changed so much from his day to ours.

Read the complete article in The University Bookman

Remembering an Eastern Orthodox Prophet: Nicholas Berdyaev, by Bradley J. Birzer

One kind of weird but enticing academic puzzle for me is discovering and delving into the works of interesting figures of the 20th century who have been largely forgotten. And, by “interesting figures,” I mean especially those who espoused types of religious humanism and their allies.

TIC mastermind Winston Elliott feels the same way, and one of the purposes of founding TIC was to bring the memory of these humanists back to the public and honor each as a vital ancestor to our own broad cause in the twenty-first century.

Everyone remembers, for example, G.K. Chesterton, T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and, more recently, Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy. Even if one hasn’t read any of their respective works, their names circulate with familiarity even in the darker corners of American civilization.

At a different, slightly lower level hover Irving Babbitt, Hilaire Belloc, Paul Elmer More, Willa Cather, Christopher Dawson, Jacques Maritain, Etienne Gilson, Josef Pieper, Walter Miller, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, and Russell Kirk.

But only a very few remember eccentrics such as T.E. Hulme, Aurel Kolnai, Leo Ward, Sister Madeleva Wolff, Wilhelm Roepke, Romano Guardini, Gabriel Marcel, Owen Barfield, Theodore Haecker, David Jones, Tom Burns, and Bernard Wall.

Nicholas Berdyaev (1874-1948), a member of this last group, has been sadly neglected as well, at least by those in conservative and libertarian circles.

He was, not surprisingly, connected to many Christian Humanists of his day. He knew the Maritains well, and while C.S. Lewis mostly dismissed his work as a sideline show, Christopher Dawson considered Berdyaev’s thought central to the restoration of the 20th-century West.

The trump card, here, though is from a fellow Russian. A figure no less important or heroic than Alexandr Solzhenitsyn discussed Berdyaev briefly in volumes II and III of The Gulag. He was, Solzhenitsyn wrote, offering perhaps the highest praise possible, “a man.”

In volume II, he described Berdyaev as the ultimate person to reject Soviet terror.

So what is the answer? How can you stand your ground when you are weak and sensitive to pain, when people you love are still alive, when you are unprepared? What do you need to make you stronger than the interrogator and the whole trap? From the moment you go to prison you must put your cozy past firmly behind you. As the very threshold, you must say to your self: ‘My life is over, a little early to be sure, but there’s nothing to be done about it. I shall never return to freedom. I am condemned to die–now or a little later. But later on, in truth, it will be even harder, and so the sooner the better. I no longer have any property whatsoever. For me those I love have died, and for them I have died. From today on, my body is useless and alien to me. Only my spirit and my conscience remain precious and important to me.’ Confronted by such a prisoner, the interrogation will tremble. Only the man who has renounced everything can win that victory. But how can one turn one’s body to stone? Well, they managed to turn some individuals from the Berdyayev [sic] circle into puppets for a trial, but they didn’t succeed with Berdyayev. They wanted to drag him into an open trial; they arrested him twice; and (in 1922) he was subjected to a a night interrogation by Dzerzhinsky himself. Kamenev was there too (which means that he, too, was not averse to using the Cheka in ideological conflict). But Berdyayev did not humiliate himself. He did not beg or plead. He set forth firmly those religious and moral principles which had led him to refuse to accepted the political authority established in Russia. And not only did they come to the conclusion that he would be useless for a trial, but they liberated him. A human being has a point of view!”

In volume 3 of The Gulag, Solzhenitsyn wrote simply: Berdyaev was a “philosopher, essayist, brilliant defender of human freedom against ideology.”

Exiled from Russia in 1922 after surviving three Soviet trials against him, Berdyaev settled in Paris, living there until his death in 1948.

While in Paris, Berdyaev became an integral part of the Jacques and Raissa Maritain circle. Indeed, as Berdyaev remembers it in his fine autobiography, Dream and Reality, he and Jacques served as equal poles in the creation and perpetuation of the group. Though Maritain’s extreme Thomism struck Berdyaev as a form of Catholic ideology, he respected the French philosopher immensely. He did joke, however, that Maritain’s fear and rejection of Protestantism and Protestants was a strange element of the convert, implying a certain irrationality.

When Christopher Dawson and Tom Burns first formed the Order group in Chelsea, London, employing the resources of the publishing house Sheed and Ward to unify all humanists of British and Europe backgrounds, Dawson immediately sought out Maritain and Berdyaev. Each contributed to one of the best book series of the last century, the 16 volume Essays in Order. As it turned out, Essays in Order served as the one attempt in the twentieth century to bring all Christian Humanists together into a unified Republic of Letters.

When Essays in Order folded, Dawson continued the same project with a second friend, Bernard Wall, publishing a journal, Colosseum. Again, Dawson and Wall sought out and received the contributions and acclaim of Berdyaev and Maritain.

One of Berdyaev’s most interesting books–and presumably the reason Dawson thought so highly him–was his The End of Our Time, written between 1919 and 1923 and published for the first time in English in 1933 by Sheed and Ward. In almost every way, though clearly a Russian and a member of the Eastern Orthodox faith, Berdyaev anticipated the major arguments of the English-Welsh Roman Catholic Dawson.

In particular, Berdyaev stressed the primacy of culture and theological issues over politics and economics as truer forms of reality. Almost the entire western world, Berdyaev argued, had embraced some form of materialism after the collapse of Christendom. And, this moved the world rapidly toward unreality.

“We must begin to make our Christianity effectively real,” Berdyaev wrote, “by a return to the life of the spirit.” Economic matters, he continued, “must be subordinated to that which is spiritual, [and] politics must be again confined confined within their proper limits.”

read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Testing the Metaphor, by JP O’Malley

In the program Frost on Interviews, recently rebroadcast on British television, the distinguished journalist David Frost attempts to understand what makes a compelling interview. In particular, the program focuses on the actions of the interviewer: should one take a relaxed or heavy-handed approach with their guest?

This approach would not have fit too comfortably in an interview with the late J. G. Ballard, whose Extreme Metaphors is light-years away from the Frost approach.

For J. G. Ballard—arguably one of the most important prose fiction writers to contribute to British culture in the post-war period—an interview wasn’t just an opportunity to flog his latest novel, talk about his characters, or name check his literary heroes.

Any time Ballard indulged a journalist—usually at his home in Shepperton—for an intimate chat, the occasion became almost an experiment where the writer tests his hypothesis with his interlocutor.

We see a remarkable example of this in a conversation from 1974, when journalist Carol Orr asks Ballard for a prediction about the future of Western culture. He responds by speaking about a society where people “want to be alone and watch television.”

Orr, horrified at what she clearly perceived to be an immoral and apocalyptic outcome, says she wants to be neither in a traffic jam, or “alone on a dune, either.” To which Ballard replies, “Being alone on a dune is probably a better description of how you actually lead your life than you realize.”

The interview ends shortly afterwards, but it’s exemplary of Ballard taking the format and twisting it to his advantage in the same way a writer does with an essay: meandering around different ideas, following the intellect at all times, but never attempting to arrive with a definitive polemic, or thesis, at the final destination.

For Ballard, the interview is a fitting moment to take images from his artistic landscape and see how they fit into the society of which we are all supposedly a part: the nightmare marriage between sex and technology in Crash, the empty swimming pools and vast deserted cities in Cocaine Nights, or the preoccupation with class consciousness in High Rise. All become topics open for discussion.

The book includes over forty-four different interviews spanning a period of forty-one years, and many of the quotes it contains read like aphorisms: “Most of us lead comparatively isolated lives”; “There is a darker corner of the human psyche that intrigues us”; “The automobile represents an extension of one’s own personality.”

Read the complete article in The University Bookman