Eugenio Corti, il cantastorie del Regno, by Giulia Tanel

La sera di martedì 4 febbraio Eugenio Corti ha fatto ritorno al Padre. Classe 1921, lo scrittore aveva conformato la sua vita al versetto del Padre Nostro che recita “Venga il Tuo Regno”, combattendo la buona battaglia tramite la scrittura.

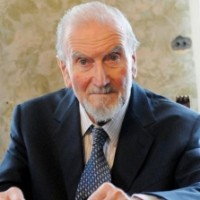

Uomo dal portamento distinto e dal fare pacato ma anche caparbio, Corti scrutava con i suoi attenti occhi azzurri i tanti lettori, molto spesso giovani, che si recavano a trovarlo nella sua casa in Brianza. Personalmente ricordo il suo atteggiamento vigoroso e paterno, dettato e supportato dalle decisive esperienze maturate durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale e da una fede granitica. Dialogando con lui si aveva la percezione di essere di fronte a un maestro da cui attingere preziose considerazioni sul passato e sull’epoca contemporanea; nel contempo, emergeva anche la consapevolezza di essere in presenza di una persona cui – da cattolici – guardare come modello di comportamento, perché lo sguardo di Corti, benché permeato di un sano realismo, era sempre orientato a Dio.

Non a caso, accanto all’età d’oro greca, il periodo storico più amato dallo scrittore brianteo era il Medioevo, ossia l’epoca in cui il messaggio cristiano si è diffuso in maniera capillare ed è diventato un fenomeno ‘di popolo’, dando luogo alla Res Publica Christiana. In quei secoli, troppo spesso classificati come ‘bui’ e invece ricchissimi sotto diversi aspetti, ogni ambito del vivere quotidiano era orientato – seppur con le dovute eccezioni – agli ideali del Vangelo: dal modo di concepire la guerra e la cavalleria, allo sviluppo dell’arte pittorica e architettonica, al ruolo assegnato alle donne… E proprio riguardo quest’ultimo aspetto, entrando nella casa di Corti si rimaneva piacevolmente colpiti dalla presenza riservata, ma assolutamente rilevante, di sua moglie Vanda, che lo scrittore contemplava ancora con sguardo innamorato e riconoscente, nonostante fossero sposati dal 1951.

Ma si diceva della centralità della fede nella vita e nel pensiero di Corti, la quale trova conferma anche nei suoi articoli e nei libri – molto vari per genere e argomento – ch’egli ha scritto dal 1947 in avanti. Tra questi spicca per importanza il romanzo storico Il Cavallo Rosso (Edizioni Ares, 1983), oramai giunto alla ventinovesima edizione e tradotto in otto lingue. Questo testo – che ha richiesto a Corti ben undici anni di lavoro – narra le vicende di alcuni ragazzi della Brianza e del loro incontro con il mondo esterno, sullo sfondo dei grandi avvenimenti storici succedutisi in Italia e nel mondo tra il 1940, anno dell’entrata in guerra dell’Italia, e il 1974, anno del referendum sul divorzio. Scorrendo pagina dopo pagina, moltissimi lettori sono rimasti avvinti nella narrazione e – oltre ad aver potuto rivivere quasi in presa diretta gli anni del secondo conflitto mondiale e della ricostruzione – hanno avuto modo di apprezzare le riflessioni storiche, teologiche e teleologiche che Corti non mancava mai di inserire nei propri scritti, in forma più o meno diretta.

Un’altra opera fondamentale lasciataci dallo scrittore brianteo è Il fumo nel Tempio (Edizioni Ares, 1996), una raccolta di articoli scritti dal 1970 in poi sulla difficile situazione della Chiesa nel post Concilio, sulla perdita di valori della società, sulla crisi della politica e in particolare della Democrazia Cristiana e, infine, sull’egemonia di una cultura di matrice laica e troppo spesso ideologizzata. Sono testi di una lucidità spesso disarmante, propria di un osservatore attento e onesto qual era Corti, convinto che il parametro di giudizio cui fare riferimento è sempre l’insegnamento di Cristo, perché solo in questo modo è possibile vivere in pienezza e gustare anche in terra un imperfetto assaggio di felicità e di Bellezza.

Sintomatica di quest’approccio alla vita è la risposta data da Corti alla domanda su quale fosse la cosa più bella che gli sia mai accaduta: «L’essere venuto al mondo, sicuramente. La prova è stata anche dura, come per tutti. Ma è stato l’esistere, l’essere, che mi ha aperto tutte le altre porte. Anche quella della consolante Speranza cristiana in una felicità intramontabile in Dio, dopo la morte terrena».

Al termine di una vita intensa e luminosa, la poesia posta da Eugenio Corti in calce alle 1274 pagine che compongono Il Cavallo Rosso appare quasi come un suo testamento: “Ecco, ora svaniscono, / i volti e i luoghi, con quella parte di noi che, come poteva, / li amava, / Per rinnovarsi, trasfigurati, in un’altra trama” (T.S. Eliot). Requiescat in pace!

Published in La nuova bussola quotidiana

A Scottish Remembrance of Russell Kirk, by Alvino-Mario Fantini

The Conservative Mind‘s author taught generations to re-enchant the world.

As an undergraduate, my first encounters with Professor Jeff Hart and The Dartmouth Review eventually led to my discovery of the works of Russell Kirk. Like William F. Buckley Jr., Kirk wrote about the need to raise, as historian George Nash put it, a “full-scale challenge to modernity”—in the arts, literature, religion, and politics. While both Buckley and Kirk enchanted me with their obvious love of language and mastery of words, it was Kirk who also managed to stir my spirit with an affection, kindness, and warmth that I did not find elsewhere. Here was a gentle, conservative aesthete.

But I’m not the only one who was affected in such a way by Kirk. And last year, to mark the 60th anniversary of the publication of his most famous work, The Conservative Mind, there were several tributes. Last summer, The University Bookman, which Kirk founded in 1960, published an on-line symposium discussing the book. In July, the Liberty Fund also published a tribute, along with three excellent rejoinders. In September, two more events took place: Lee Edwards at the Heritage Foundation hosted a panel with Matthew Spalding, Yuval Levin, and Peter Wehner to discuss the book’s impact; and a few days later, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, The Imaginative Conservative, and the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal co-sponsored a one-day seminar at Houston Baptist University.

Scottish Celebrations

One of the more interesting commemorations took place October 18-20 in Scotland, where a distinguished group of students and academics joined members of the Kirk family and their close friends at the University of St. Andrews to discuss The Conservative Mind—and to remember, in Willmoore Kendall’s words, the “benevolent sage of Mecosta”.

Some people aren’t aware that Kirk was a doctoral student at the University of St. Andrews; in fact, he remains the only American to have received a Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) from that esteemed university. His dissertation, titled “The Conservative’s Rout”—later re-named The Conservative Mind in discussions with publisher Henry Regnery—is still on file at the university, and the anniversary celebrations in Scotland began, appropriately enough, with a viewing of the original dissertation on Friday afternoon.

Attending the weekend’s events were a dozen or so promising young Americans, all current or former Wilbur Fellows who, after working for Russell and Annette Kirk, went on to study at St. Andrews. It was impressive to hear the deep affection with which each of them spoke about the Kirks—and about the time they spent at his ancestral home at Piety Hill.

Various Europeans also joined the celebrations—for, despite his focus on an ‘Anglo-American’ political tradition, many of Kirk’s published works are known across Continental Europe. Some have even been translated into Spanish, German, and Italian, and his ideas have influenced a range of European scholars. In Germany, Kirk’s contributions as a ‘conservative man of letters’ were recognized as so important, that he merited a lengthy entry (and photograph) in the Lexikon des Konservatismus (Dictionary of Conservatism), a 1996 work edited by the German noble, Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. Today even young members of Sweden’sKonservativt Forum are wont to quote Kirk approvingly.

The always charming and energetic Annette Kirk was also present in Scotland, along with two of her daughters and their families. On Friday evening, she hosted a private reception and dinner at the cliff-side Russell Hotel, where guests were treated to a talk by André Gushurst-Moore, currently Director of Pastoral Care at Downside School, an institution attached to the Benedictine Downside Abbey in Somerset, England.

Gushurst-Moore elaborated on some of the principal themes in Kirk’s works, speaking of Kirk’s defense of humane learning, the moral imagination, and “the permanent things.” Not coincidentally, these are precisely the themes closest to Gushurst-Moore’s own work. In his recent The Common Mind: Politics, Society and Christian Humanism from Thomas More to Russell Kirk (published in 2013 by Angelico Press), he profiles 12 great ‘Christian Humanists’ through the centuries, including Thomas More, Dr. Johnson, Edmund Burke, Orestes Brownson, and Russell Kirk, among others.

His was an eloquent and respectful tribute, which many found quite moving. It was a testament of sorts to the impact that Kirk’s writings—and his gentle character—had on people. And nearly two decades after his death, Kirk continues to touch people with the evocative power of his words (the late Frederick Wilhelmsen said “Kirk was essentially a poet who wrote in prose”). What a reminder of those T.S. Eliot lines from Four Quartets which Kirk was so fond of quoting: “the communication / Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.”

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

A Noble Imagination: Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley, by James P. Bernens

If you would wish for your children to garner a love and fascination for the good things of God’s Creation, if you would have them embrace adventure, cherish what is noble, honor the poor, and attain to a sincere civility and gentleness, let them read from the works of Sir Walter Scott.

Born in 1771 in the city of Edinburgh, Walter Scott came of age in a century that had seen the uneasy political union of the kingdoms of England and Scotland, and was about to see the upheaval of the American and French Revolutions. Drawing from the deep well of British and medieval history, Scott established himself as one of the premier poets of his age, and one of the finest pure storytellers the English language has ever seen. His first novel, Waverley, remains once of his best, although it is less recognizable to modern readers than many other excellent titles like Ivanhoe and Rob Roy.

First published in 1814, Waverley is a lovely and heroic tale which follows the journey of young Edward Waverley, an impressible English gentleman and army officer, who is posted to duty in the tumultuous scene of eighteenth-century Scotland. Mindful of the old Royalist history of his own family, and carried on a string of fate that brings him into league with a Highland clan, Waverley becomes embroiled in the 1745 “Jacobite” rebellion, which seeks to replace Britain’s King George with the exiled Catholic Stuarts. If this chapter of British history sounds obscure, the reader may be comforted to know that much context is incorporated into the fabric of the story by the keen antiquarian mind of Sir Walter Scott himself.

More than anything, Waverley evolves into an adventurous ramble through the genteel courts and fearsome wilds of Scotland and England. There are portions of the novel which simply cannot be forgotten: as when Waverley stands enchanted by the Gaelic music of beauteous Flora Mac-Ivor; or when the rash hero suddenly finds himself pledging his sword in the service of the charismatic Jacobite leader, Bonnie Prince Charlie; or when the great Catholic Highland chieftain, the Vich Ian Vohr, manfully meets his end with the laughing phrase, “This is well got up for a closing scene.”

But the excellence of Waverley extends beyond the many opportunities for suspense and enjoyment which it affords the reader. Like much else that Scott wrote, it provides a lesson in poetry and healthy imagination, and reassures the observant mind of the goodness of the age-old morals. It was this quality in Scott’s writing which drew the special admiration of another venerable Briton, the famous Catholic convert John Henry Newman. In 1839, six years before his conversion to Rome, Newman wrote:

During the first quarter of this century a great poet [Scott] was raised up in the North, who, whatever were his defects, has contributed by his works, in prose and verse, to prepare men for some closer and more practical approximation to Catholic truth. The general need of something deeper and more attractive than what had offered itself elsewhere, may be considered to have led to his popularity; and by means of his popularity he re-acted on his readers, stimulating their mental thirst, feeding their hopes, setting before them visions, which, when once seen, are not easily forgotten, and silently indoctrinating them with nobler ideas, which might afterwards be appealed to as first principles.

Newman saw in Scott’s writing—of which Waverley is a foremost example—an excellence and superiority that helped move men’s minds towards a healthy Christian culture. For the same reason, Dr. Russell Kirk, writing in 1993, esteemed Sir Walter Scott as one of his ten exemplary conservatives in the history of Western Civilization.

Now, after all this has been said, you might be moved to ask: “If this is true, why have I heard and seen so little of the books written by this eminent Scotsman?”

Read the complete article in Crisis Magazine