Solzhenitsyn: The Courage to be a Christian, by Joseph Pearce.

In these dark days in which the power of secular fundamentalism appears to be on the rise and in which religious freedom seems to be imperiled, it is easy for Christians to become despondent. The clouds of radical relativism seem to obscure the light of objective truth and it can be difficult to discern any silver lining to help us illumine the future with hope.

In such gloomy times the example of the martyrs can be encouraging. Those who laid down their lives for Christ and His Church in worse times than ours are beacons of light, dispelling the darkness with their baptism of blood. “Upon such sacrifices,” King Lear tells his soon to be martyred daughter Cordelia, “The gods themselves throw incense.”

It is said that the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church and, if this is so, more bloody seed has been sown in the past century than in any of the bloody centuries that preceded it. Tens of millions have been slaughtered on the blood-soaked altars of national and international socialism in Europe, China, Cambodia and elsewhere. Today, in many parts of the world, millions upon millions are being slaughtered in the womb in the name of “reproductive rights.”

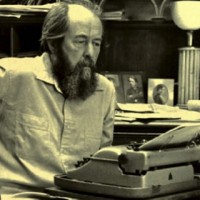

In such a meretricious age the giant figure of Alexander Solzhenitsyn emerges as a colossus of courage. Born in Russia in 1918, only months after the secular fundamentalists had swept to power in the Bolshevik Revolution, Solzhenitsyn was brainwashed by a state education system which taught him that socialism was just and that religion was the enemy of the people. Like most of his school friends, he enslaved himself to the zeitgeist, became an atheist and joined the communist party.

Serving in the Soviet army on the Eastern Front during the Second World War he witnessed cold blooded murder and the raping of women and children as the Red Army took its “revenge” on the Germans. Disillusioned, he committed the indiscretion of criticizing the Soviet leader Josef Stalin and was imprisoned for eight years as a political dissident.

While in prison, he resolved to expose the horrors of the Soviet system. Shortly after his release, during a period of compulsory exile in Kazakhstan, he was diagnosed with a malignant cancer in its advanced stages and was not expected to live. In the face of what appeared to be impending death, he converted to Christianity and was astonished by what he considered to be a miraculous recovery.

Throughout the 1960s Solzhenitsyn published three novels exposing the secularist tyranny of the Soviet Union and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. Following the publication in 1973 of his seminal work, The Gulag Archipelago, an exposé of the treatment of political dissidents in the Soviet prison system, he was arrested and expelled from the Soviet Union, thereafter living the life of an exile in Switzerland and the United States. He finally returned to Russia in 1994, after the collapse of the Soviet system.

In 1978, Solzhenitsyn caused great controversy when he criticized the secularism and hedonism of the West in his famous commencement address at Harvard University. Condemning the nations of the so-called free West for being morally bankrupt, he urged that it was time “to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.”

Read the complete article in Crisis Magazine

Islam and the Closing of the Secular Mind, by Samuel Gregg

Given the decidedly strange response of the Obama Administration and much of the Western commentariat to the violence sweeping the Islamic world, one temptation is to view their reaction as simple incomprehension in the face of the severe unreason that leads some people to riot and kill in a religion’s name. But while the Administration’s response has plenty to do with trying to defend a foreign policy that has plainly gone south, it also reflects something far more problematic: the Western secular mind’s increasing inability to think seriously and coherently about religion at all.

This problem manifests itself in several ways. The first is the manner in which many secular thinkers seem to regard all religions as “basically the same.” By this, they often mean either equally irrational or as promoting essentially similar values.

A moment’s reflection would indicate to even the most militant atheist that this simply isn’t true. Islam and Christianity, for instance, have very different understandings of who Jesus Christ is. Christians believe that he is God, the second Person of the Trinity. Muslims do not. Ergo, Islam and Christianity are not effectively the same. At their respective cores are fundamentally irreconcilable theological positions. It’s also very difficult to find robust affirmations of free will outside Judaism and Christianity (at least the orthodox varieties of these two faiths).

Likewise, as any informed Muslim will tell you, Islamic theology has no real equivalent of the Christian idea of the church. The Greek word for “church” (ekklesia) literally means to be “called out.” That, alongside Christ’s words about the limits to Caesar’s power, had immense implications for how Christians think about the state and its relationship to religion. Among other things, it means Christianity has always maintained significant distinctions between the temporal and the spiritual realms that are far less perceptible — again, as any pious Muslim will inform you — in Islamic theology and history.

All this, however, is a little complicated for those secular intellectuals who simply regard religion as just another lifestyle-choice rather than being essentially about people’s natural desire to (1) know the truth about the transcendent and (2) live their lives in accordance with such truths.

Read the complete article in Catholic Education Resource Center

Why Study the West?, an interview with Robert P. George .

The new issue (Vol. 25, No. 1, March 2012) of Academic Questions, the excellent journal of the National Association of Scholars, is devoted to the study of Western civilization. It includes interesting articles by Charles Butterworth, Robin Fox, Stephen Balch, and others. It also includes an interview I gave to editor-at-large Carol Iannone.

=============

Why Study the West? An Interview with Robert George

by Carol Iannone, editor-at-large of Academic Questions

Iannone: Why is Western Civilization worth studying in your view?

George: By any standard of measure, the intellectual, moral, religious, political, economic, scientific, technological, artistic, architectural, and literary achievements of the West are extraordinary. It would be foolish not to study them, examine their roots, and explore the complex relationships among them, such as the relationship between Western religious ideas and the development of science. Our students are—as we ourselves are—inheritors of these achievements. Their culture—and, thus, their lives—have been shaped by them. They deserve to understand them. And if they are to maintain all that is worth maintaining, and reform what needs reforming, and pass along to their own children a vibrant and healthy culture, they need to understand them.

Iannone: What about Western Civilization is unique?

George: Science as we know it could not have developed outside of the West. It is a great gift of the West to the entire world. Moreover, ideas of natural law, republican government, civil rights and liberties, and the dignity, inviolability, and fundamental freedom of the individual are fundamentally Western insights. These, too, are gifts to the world. Many of these insights were hard-won. Some might yet be lost. Certainly, they have not always been honored, or fully respected, by the people of the West or their political, religious, and cultural institutions. Still, they are exceptional achievements.

Iannone: How important are Judaism and Christianity and the moral values they foster to the maintenance of Western Civilization? Are there other essential elements of Western thought that should be part of any curriculum—certain books, ideas, developments?

George: If there were no Judaism, there would be no Christianity. There is a profound sense in which Christianity is the “other” Jewish religion emerging from the transformations in Jewish faith and practice that resulted from the destruction of the second Temple in Jerusalem. If there were no Christianity, there would be no Western civilization. Most of the great achievements of the modern West were underwritten by Christian, and therefore also by Jewish religious and philosophical and moral ideas. Of course, pre-Christian Greek and Roman thought, many of the aspects of which were taken up into Christian thought, were also profoundly important. Can these achievements be maintained if Jewish and Christian faith collapses in the West? Can Western ideals and institutions flourish when utterly severed from their religious roots? Frankly, I doubt it. But it appears that we will know for sure before too long. Much of Europe today is engaged in a vast experiment that will tell us whether cultural and political achievements whose historical roots are in religion can be sustained and nurtured in a cultural and political milieu of extreme secularism.

Read complete interview in Mirror of Justice