Talibans of Austerity, by Theodore Dalrymple

A sentence in the French newspaper Le Monde recently caught my eye: Il y aura toujours des talibans de l’austérité, there will always be the Talibans of austerity. It was uttered by the economist Jean Pisani-Ferry in an interview in the newspaper about the crisis in the Euro zone, and it made me think at once of the Confucian dictum in the Analects that the first task necessary in restoring a polity to health is the rectification of language. Words must be used correctly, for if they are not moral collapse follows.

Some linguists might object that the meaning of words shifts and is never absolutely fixed: for example, if enough people use the word disinterested to mean uninterested, then the word disinterested actually comes to mean uninterested, and the fact that it thereafter becomes difficult to express succinctly what the word disinterested once meant is quite beside the point. Will disinterestedness itself disappear just because the word for it disappears? Reasonable people might disagree as to the answer.

But language has to be tethered to relatively fixed meanings in some way or other if words are not simply to be instruments of domination à la Humpty Dumpty. Let us then, consider the phrase ‘Talibans of austerity’ and what it signifies.

Austerity, according to one of the definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary (the others are similar), is ‘severe self-discipline or self-restraint; moral strictness, rigorous abstinence, asceticism.’ But clearly this is only a part of what Prof. Pisani-Ferry means. In the professor’s usage the dictionary meaning of the word austerity is but his connotation; his denotation is the attempt, by means either of increased taxation or reduced expenditure (especially the latter, of course) to balance government budgets.

One may question the practical economic wisdom of reducing budget deficits too quickly, at least where the government accounts for so large a proportion of economic activity that drastic reductions in government expenditure might lead to a serious collapse of aggregate demand. (The fact that government expenditure should never play so important a role in any economy is not a valid objection: we always start off from where we are actually rather than where we would have been had we been wiser.) The question of the speed with which a government budget deficit is reduced, therefore, and the means by which it is done, is another of those many questions about which reasonable men may and do disagree.

But to call the attempt to balance a budget ‘austerity,’ in other words to say living within your means implies ‘rigorous abstinence, asceticism,’ a kind of killjoy puritanism, is to suggest that it is both honest, just and decent to do otherwise. And this is indicative of a revolution in our sensibilities.

Read the complete article in Library of Law and Liberty

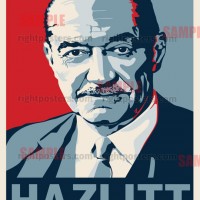

L’economia in una lezione di Hazlitt, by Marco Respinti

Correva il 1946, l’Europa era piagata dalle distruzioni della Seconda guerra mondiale (1939-1945), gli Stati Uniterano in ginocchio per lo sciagurato statalismo imposto loro dall’interminabile presidenza di Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) e il resto del mondo si dibatteva tra guai antichi e nuove schiavitù, attorcigliandosi sempre più nelle nefaste conseguenza che la lunga «guerra civile europea» aveva disseminato per l’intero pianeta e sprofondando nell’oramai apparentemente irrefrenabile avanzare del totalitarismo comunista.

Il 1946 che in pratica spezza in due il Novecento ha insomma simboleggiato il centro stesso del secolo terribile, del «secolo delle idee assassine» (come lo ha definito Robert Conquest), del secolo davvero sin troppo lungo, altro che breve. Non c’era che da risalire, certo; ma allora, come sempre, la cosa è più facile a dirsi che a farsi. Qualcosa iniziò però a muoversi attorno a diverse figure di genio, una delle quali è l’indimenticabile Henry Hazlitt (1894-1993), statunitense. Economista, filosofo, critico letterario, uomo di solida formazione classica (dedicò un’opera anche al pensiero stoico), prolifico autore di numerosi volumi e saggi, il suo nome è inscindibile legato a quello di un libro: Economics in One Lesson, un manabile di buon senso intellettuale e pratico per difendere la libertà dai molti faraoni che nella storia mirano a fare scempio dell’anima umana.

Pubblicato proprio in quell’emblematico 1946. Titolo stringatissimo – anticipatore felice degli attuali, e spesso vuoti, «101», «Mille e un modi di….» o «100 risposte per…» –, quell’opera di Hazlitt si legge in un soffio, si capisce in un attimo e non si scorda mai. Sul web la si trova ovunque, in mille vesti, sempre disponibile gratis. Ora ve n’è, a decenni di distanza, anche un’utile traduzione italiana, L’economia in una lezione. Capire i fondamenti della scienza economica (IBL Libri, Torino 2012). Finalmente è stato colmato un buco imperdonabile (mentre in lingua spagnola lo è sin dal 1947, allorché l’Editorial Kraft, di Buenos Aires, ne predispose subito una traduzione).

Si dice che l’originale in lingua inglese abbia venduto più di un milione di copie negli Stati Uniti. Opera di alta divulgazione, L’economia in una lezione è uno di quei titoli che non morirà mai, che ha fatto epoca (e un’epoca che non tramonta), che ha cambiato la storia. Vero. Ma molta della sua straordinaria importanza è legata ai tempi e al modo in cui esso nacque. Ricordavo che dopo la pace armata seguita alla conclusione sanguinosa del secondo conflitto mondiale, prima ancora che la Cortina di ferro calasse all’Est con il famoso discorso di Winston Churchill (1874-1965), la riscossa dell’Occidente ferito ma non del tutto ancora sconfitto fu capace di generare, relativamente in fretta, molte e importanti reazioni costruttive. Fra queste vi fu certamente la nascita del moderno movimento conservatore statunitense. Bene inteso, all’epoca tutto esso era tranne che un «movimento», ma i semi gravidi di futuro erano già stati ben piantati. Comparvero dunque i primi intellettuali «non allineati», i primi uomini di cultura decisi a non arrendersi al cumulo di macerie, le prime, timide e povere organizzazioni della cosiddetta «società civile», qualche raro buon editore, certi libri ottimi e persino qualche periodico.

Read the complete article in Ragion Politica