Catholic Social Teaching: It’s Time to End the Misrepresentations, by Anthony Esolen

Imagine someone appealing to Lord Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts, to justify the activities of gangs in Los Angeles.

Why not? Lord Baden-Powell wanted boys to do risky things, and what’s more dangerous than running guns or smuggling cocaine or fighting another gang in a shooting spree? He enjoined upon the Scouts a stern code of honor and loyalty, and who is more loyal than a new recruit for the Crips? Who is more willing to shed his blood for the honor of the gang?

Imagine someone appealing to Michelangelo to justify porn. Why not? Michelangelo painted nudes all over the Sistine Chapel, and Hustler and Penthouse are full of nudes. Michelangelo endured the disgruntlement of the prudish, so that the figures in his Last Judgment were later provided with discreet veils and tunics and loincloths. And aren’t Hustler and Penthouse stuck underneath the counter at convenience stores? Michelangelo admired the sculpture of ancient Greece; those ancient Greeks, for their part, traded in vases depicting acts of pedophilia. So why should a busy stockbroker in a hotel not be allowed to relax in front of a television, watching whatever delights his sophisticated tastes?

Imagine someone appealing to Florence Nightingale to justify doctor-dosed suicide. She wanted to relieve suffering, didn’t she? Imagine someone appealing to Saint Francis of Assisi to justify looting for fun and profit. His heart was with the poor, no? Imagine someone appealing to Saint Catherine of Siena to justify the modern feminist. Why, Saint Catherine dared to rebuke cardinals and popes!

Imagine a lawyer returning his fee when he loses a case; imagine a television pundit suddenly admitting that he doesn’t know what he is talking about; imagine a Hollywood starlet speaking English; imagine the Cubs winning the World Series; imagine anything most absurd, and you have not yet approached the absurdity of those who claim that Catholic Social Teaching implies the existence of a vast welfare state, bureaucratically organized, unanswerable to the people, undermining families, rewarding lust and sloth and envy, acknowledging no virtue, providing no personal care, punishing women who take care of their children at home, whisking the same children away from parental supervision and into schools designed to separate them from their parents’ views of the world, and, for all that, keeping whole segments of the population mired in a cycle of dysfunction, moral squalor, and poverty, while purchasing their votes with money squeezed by force from their neighbors.

Read the complete article in Catholic Education Resource Center

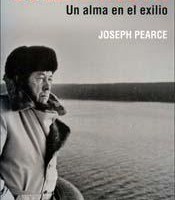

Solzhenitsyn’s Prophetic Voice: Biographer Joseph Pearce Discusses Critic of Communism, by Annamarie Adkins & Joseph Pearce

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, some people predicted that global affairs had reached “the end of history” and that democratic capitalism had definitively triumphed.

Remembering an Eastern Orthodox Prophet: Nicholas Berdyaev, by Bradley J. Birzer

One kind of weird but enticing academic puzzle for me is discovering and delving into the works of interesting figures of the 20th century who have been largely forgotten. And, by “interesting figures,” I mean especially those who espoused types of religious humanism and their allies.

TIC mastermind Winston Elliott feels the same way, and one of the purposes of founding TIC was to bring the memory of these humanists back to the public and honor each as a vital ancestor to our own broad cause in the twenty-first century.

Everyone remembers, for example, G.K. Chesterton, T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and, more recently, Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy. Even if one hasn’t read any of their respective works, their names circulate with familiarity even in the darker corners of American civilization.

At a different, slightly lower level hover Irving Babbitt, Hilaire Belloc, Paul Elmer More, Willa Cather, Christopher Dawson, Jacques Maritain, Etienne Gilson, Josef Pieper, Walter Miller, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, and Russell Kirk.

But only a very few remember eccentrics such as T.E. Hulme, Aurel Kolnai, Leo Ward, Sister Madeleva Wolff, Wilhelm Roepke, Romano Guardini, Gabriel Marcel, Owen Barfield, Theodore Haecker, David Jones, Tom Burns, and Bernard Wall.

Nicholas Berdyaev (1874-1948), a member of this last group, has been sadly neglected as well, at least by those in conservative and libertarian circles.

He was, not surprisingly, connected to many Christian Humanists of his day. He knew the Maritains well, and while C.S. Lewis mostly dismissed his work as a sideline show, Christopher Dawson considered Berdyaev’s thought central to the restoration of the 20th-century West.

The trump card, here, though is from a fellow Russian. A figure no less important or heroic than Alexandr Solzhenitsyn discussed Berdyaev briefly in volumes II and III of The Gulag. He was, Solzhenitsyn wrote, offering perhaps the highest praise possible, “a man.”

In volume II, he described Berdyaev as the ultimate person to reject Soviet terror.

So what is the answer? How can you stand your ground when you are weak and sensitive to pain, when people you love are still alive, when you are unprepared? What do you need to make you stronger than the interrogator and the whole trap? From the moment you go to prison you must put your cozy past firmly behind you. As the very threshold, you must say to your self: ‘My life is over, a little early to be sure, but there’s nothing to be done about it. I shall never return to freedom. I am condemned to die–now or a little later. But later on, in truth, it will be even harder, and so the sooner the better. I no longer have any property whatsoever. For me those I love have died, and for them I have died. From today on, my body is useless and alien to me. Only my spirit and my conscience remain precious and important to me.’ Confronted by such a prisoner, the interrogation will tremble. Only the man who has renounced everything can win that victory. But how can one turn one’s body to stone? Well, they managed to turn some individuals from the Berdyayev [sic] circle into puppets for a trial, but they didn’t succeed with Berdyayev. They wanted to drag him into an open trial; they arrested him twice; and (in 1922) he was subjected to a a night interrogation by Dzerzhinsky himself. Kamenev was there too (which means that he, too, was not averse to using the Cheka in ideological conflict). But Berdyayev did not humiliate himself. He did not beg or plead. He set forth firmly those religious and moral principles which had led him to refuse to accepted the political authority established in Russia. And not only did they come to the conclusion that he would be useless for a trial, but they liberated him. A human being has a point of view!”

In volume 3 of The Gulag, Solzhenitsyn wrote simply: Berdyaev was a “philosopher, essayist, brilliant defender of human freedom against ideology.”

Exiled from Russia in 1922 after surviving three Soviet trials against him, Berdyaev settled in Paris, living there until his death in 1948.

While in Paris, Berdyaev became an integral part of the Jacques and Raissa Maritain circle. Indeed, as Berdyaev remembers it in his fine autobiography, Dream and Reality, he and Jacques served as equal poles in the creation and perpetuation of the group. Though Maritain’s extreme Thomism struck Berdyaev as a form of Catholic ideology, he respected the French philosopher immensely. He did joke, however, that Maritain’s fear and rejection of Protestantism and Protestants was a strange element of the convert, implying a certain irrationality.

When Christopher Dawson and Tom Burns first formed the Order group in Chelsea, London, employing the resources of the publishing house Sheed and Ward to unify all humanists of British and Europe backgrounds, Dawson immediately sought out Maritain and Berdyaev. Each contributed to one of the best book series of the last century, the 16 volume Essays in Order. As it turned out, Essays in Order served as the one attempt in the twentieth century to bring all Christian Humanists together into a unified Republic of Letters.

When Essays in Order folded, Dawson continued the same project with a second friend, Bernard Wall, publishing a journal, Colosseum. Again, Dawson and Wall sought out and received the contributions and acclaim of Berdyaev and Maritain.

One of Berdyaev’s most interesting books–and presumably the reason Dawson thought so highly him–was his The End of Our Time, written between 1919 and 1923 and published for the first time in English in 1933 by Sheed and Ward. In almost every way, though clearly a Russian and a member of the Eastern Orthodox faith, Berdyaev anticipated the major arguments of the English-Welsh Roman Catholic Dawson.

In particular, Berdyaev stressed the primacy of culture and theological issues over politics and economics as truer forms of reality. Almost the entire western world, Berdyaev argued, had embraced some form of materialism after the collapse of Christendom. And, this moved the world rapidly toward unreality.

“We must begin to make our Christianity effectively real,” Berdyaev wrote, “by a return to the life of the spirit.” Economic matters, he continued, “must be subordinated to that which is spiritual, [and] politics must be again confined confined within their proper limits.”

read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative