Conservative Credo, by Barbara J. Elliott

Conservatism seeks the Truth that has emerged over time, drawing from the deep wellsprings of human experience, and builds anew on foundations that have withstood the tests of time. It fosters order and the flourishing of human beings as they live in relationship with one another. We are united in the eternal contract between the dead, the living, and the yet unborn.

Conservatism is rooted in the acknowledgement that God is our Creator and that the human soul sojourns through this realm toward its eternal transcendent fulfillment. We are all flawed human beings in need of redemption, capable of great evil as well as great good.

Because man is fallible by nature, the conservative seeks to limit the damage that can be done through the abuse of power by limiting its concentration.

The conservative fosters the fullness of human potential by protecting the freedom and dignity of each individual, acknowledging that responsibility comes with freedom. Rights and duties are always linked.

For the conservative, each man and woman is equal in dignity and equal before the law, but gloriously individual and unequal in talents, aptitudes, and outcomes. The conservative celebrates the uniqueness of individuals and does not level to eliminate differences.

The conservative honors the family as the essential building block of civilization, the house of worship as the locus for forming culture, and the community as the matrix for human interaction. Culture and community grow from relationships and affinities over time, rooted in place. Conservatives value the rich diversity of relationships, organizations, and private associations that make up civil society and intermediary institutions.

The conservative values subsidiarity because we know many of the best solutions to human problems are found at the level closest to the individual person. We foster personal, local care for persons in need, preferably face-to-face with someone whose name we know. We believe that human transformation occurs best in the context of a personal, loving relationship, with accountability, over time.

The conservative is more concerned with the culture than politics, because the political realm is a derivative one, not primary, in human existence. Political problems are at their root moral and spiritual problems, which blend into the economic realm. Political change is rooted in cultural change.

Conservatives believe that caring for our neighbor is so important that it should not be left to the government. The one thing government cannot do is love. That is what we are called to do in the private sector, with our own time, talent, and treasure.

The conservative believes that that the True, the Good, and the Beautiful are interrelated, and that all things are measured against these three transcendentals.

We believe that there is Truth, that it is knowable, and that it is our duty to seek Truth and live it throughout our lives. The conservative believes that the virtues of Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance should be practiced in both private and public life. We believe that virtues, not values, define the human soul.

We believe that Love is the highest motivation of the human person and that the purpose of life itself is to know God, to love Him and serve Him, and to love our neighbor as ourselves. Our ultimate fulfillment is in the transcendence of love.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

To Whom Do Children Belong?, by Melissa Moschella

Children belong not to parents, but to the whole community. So claimed Melissa Harris-Perry in a recent MSNBC promo spot that has sparked heated controversy.

Harris-Perry argued that if we are going to start investing adequately in our public schools, “we have to break through our kind of private idea that kids belong to their parents or kids belong to their families and recognize that kids belong to whole communities.”

Now, if she simply meant that families and community members should support each other with neighborly gestures, such as—to take her own example—offering to drive a child home from school when the parents temporarily cannot, then her position is hardly controversial.

But her words are much more than just an exhortation to neighborliness or volunteerism. They reflect the troubling but not uncommon view that the education of children, particularly their formal education, is first and foremost the task of the state rather than parents, and that the state has primary educational authority over children, at least once they are old enough to attend school.

This is effectively the position that political theorists such as Amy Gutmann and Stephen Macedo take when they argue, for instance, that the state can and should require children to be exposed to values and ways of life that conflict with those they are learning at home, that the state at least in principle has the right to mandate such “diversity education” programs even in private schools and home schools, and that parents in principle have no right to opt their children out of such programs, even if they have a moral or religious objection to their content.

Read the complete article in Public Discourse

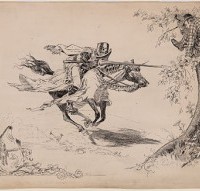

Mark Twain and Russell Kirk against the Machine

Though neither an humanist nor a Christian—nor, for that matter, even a romantic in the vein of Blake who feared the “dark Satanic mills” of Industrial England—Mark Twain identified the late-nineteenth century fear of the machine run amok perfectly in his last novel, the tragically whimsical A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. One of the first to use time travel as a plot device, the story revolves around Hank Morgan, an engineer devoid of any poetry or sentiment. As his German last name indicates, he is the man of “tomorrow.” A practical man schooled in the servile rather than the liberal arts, Morgan can create almost any type of mechanism: “guns, revolvers, cannon, boilers, engines, all sorts of labor-saving machinery.” A materialist, he “could make anything a body wanted—anything in the world, it didn’t make a difference what; and if there wasn’t any quick new-fangled way to make a thing, [he] could invent one.” He was also, Hank assures the reader, “full of fight.” And, a conflict employing crowbars with one of his employees, a man named Hercules, results in severe blow to Morgan’s head, knocking him unconscious.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative