The Glamour of True Ideas (interview with Roger Scruton), by Ferenc Hörcher

Mos Maiorum’s Ferenc Hörcher recently interviewed British philosopher Roger Scruton in Bercel, Hungary at the Common Sense Society’s 2012 Summer Leadership Academy. Mr. Scruton shares his thoughts about European intellectual elites, Hungarian national identity and sovereignty, and why young people are still interested in ideas.

Ferenc Hörcher: Professor Scruton, let us first talk about the recent political events in Hungary and Europe. I don’t know how well you are acquainted with the Hungarian situation, but you might have heard the news that an IMF delegation recently came to Hungary to prepare talks about some sort of an agreement and financial support for the Hungarian budget. Do you regard it as a danger for a government’s financial policy and sovereignty to take this sort of help, or can there be situations when it is useful?

Roger Scruton: Well, all help of this kind diminishes sovereignty. Because you become answerable to the international body about the use of your own budget. We have seen proof of this in the case of Greece. Greece has essentially lost economic sovereignty and it will not be able to regain it except if it withdraws from the Eurozone now. In the Hungarian case, too, it is undeniably true that there will be some loss of sovereignty in that the government and future governments will have to comply with the conditions of the loan, which may involve making decisions about taxes and about the disposition of economic growth and so on. This same phenomenon we can confront in our own lives as well: if one accepts a mortgage, a loan from a bank to buy a house, the structure of one’s whole life will be changed. But we accept it because we assume that nevertheless the change is for the better. Let us say the good consequences outweigh the bad.

FH: Will the good outweigh the bad in the Hungarian case?

RS: I think that he Hungarian government hopes for the same positive balance from an agreement with the IMF. Although I have to say I never understood how this institution works, and I don’t think the people who run the IMF understand how it works particularly, because none of them seem to be trained in anything except politics.

FH: What do you think of Mr. Orbán’s international manoeuvring in general? He has many adversaries and opponents in Europe, including in the European Parliament and in the media. Do you not think that to take an independent national stance is too risky in a situation like ours? Or do you agree with those who consider him an example for other countries looking to put their own national interest first?

RS: I would say that Mr. Orbán’s approach to the IMF is probably the right one. Hungary is in a difficult situation economically like all the countries in this region, and it needs short term help in order to achieve long term stability. Here is some short term help offered by the wrong kind of institution. But I think, Mr. Orbán’s approach is, as you say, to put the national interest first, and make sure as far as he can that the terms of the loan are such that the country will be able to pay it back by the time required.

FH: This achievement presupposes a rather delicate, nuanced way of negotiating.

RS: It is hard to know how far this is possible at all! One of the key questions is whether it will end up as a semi-permanent debt or a temporary one. Most people say that permanent debts in the end are in fact gifts, because effectively you are not paying it back. It is simply there in the background of all your dealings, and the person who gave the gift turns out to be the stupid one because he has lost the money. There is plenty of evidence that the IMF will in the long run function in that way. It will just be one way of transferring capital assets from one part of the global economy to another.

FH: Do you think that political prices will have to be paid for that?

RS: I am sure that is true. But that is where you have to be a clever politician to try and get the reward without paying too high a price for it.

FH: Because of Mr. Orbán’s manoeuvering there have been many anti-Hungarian reactions in Europe and elsewhere in the whole Western world. On the other hand, in certain countries, such as in Poland, Orbán is taken for a kind of hero. What sort of positive role might Orbán play in the present situation of the European and global crisis?

RS: I think that is a more interesting political question, really. Because the question about the IMF is not really to do with Mr. Orbán’s politics. There are plenty of countries presently appealing to the IMF and Hungary just happens to be one of them. When it comes to the European Union there are interesting issues which are peculiarly Hungarian. The European Union, as you know, is centred upon the alliance of France and Germany, and in particular on the German need to whitewash its past, to persuade the world that Germany is a civilised nation which has nothing to do with that Nazi episode.

FH: Does it not overplay this role?

RS: It does. Because the German political class is constantly looking for some right wing extremist governments to contrast itself with. And Hungary is a wonderful example, because first of all Germans imposed fascism on Hungary, and forced Hungary in a position which many people today feel ashamed of.

Read the complete article in Paprika Politik

A Summer With Virgil, by Bruce Thornton

From Homer’s Iliad to Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War, these five classics make for sublime and delightful beach reading.

“To read the Latin & Greek authors in their original,” Thomas Jefferson once wrote, “is a sublime luxury.” Fortunately, for those who don’t read Greek and Latin, the great works of Classical literature are available in first-rate translations. The following five classics are some of the best works from the astonishing variety and brilliance of Greek and Roman literature.

![]()

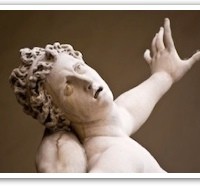

Homer, Iliad

The first work of Western literature was written around 750 B.C. The Iliad tells the story of only a few weeks from the ten years of the Greek war against Troy, ignited when Helen ran off with the Trojan Paris. But the Iliad is more than just a celebration of war and martial valor. To be sure, Homer’s admiration for men who will risk their lives in war for eternal glory is obvious, and his descriptions of fighting and dying are still some of the most vivid portraits of men at war we have.

But the Iliad offers much more: At its heart, it is a profound examination of what is best and worst in human nature, of what binds people together into a community and what tears them apart with bloody violence. As Homer tells the story of the “baneful wrath” of Achilles, the “best of the Achaeans,” over his dishonor at the hands of the ruler Agamemnon, he brilliantly shows us the destructive effects of the hero’s code of honor and vengeance against those, even friends, who fail to acknowledge his excellence and great deeds. Achilles’ quest for revenge, driven by a passionate anger he cannot control, in the end sacrifices his own community, his most beloved friend, and ultimately his own humanity. Homer teaches us that no society can survive when its ideals are based on personal honor and glory achieved through violence. Human community and human identity both depend on the “ties that bind,” the mutual obligations and affections we all, even the most brilliant of us, owe one another by virtue of being born into a tragic world of change, loss, and death.

Long before Aristotle, then, Homer understood that we are “political animals,” unable to live without our fellow humans because of our existential dependence on others. In the end, as we see in the moving scene in which the enemies Achilles and Priam, king of Troy, weep together over their lost loved ones, Homer teaches us that despite what divides us — no matter how exceptional our achievements and talents — it is our common subjection to time and death, and our dependence on other people we love and lose, that make us, for all our bestial passions, more than animals, and better than the immortal gods.

Read the complete article in CERC

Edmund Burke for Our Time, by William F. Byrne

[Excerpt from: William F. Byrne, Edmund Burke for Our Time: Moral Imagination, Meaning, and Politics (De Kalb, Ill.: Northern Illinois University Press, 2011).]

To the extent that there is such a thing as “Burkean conservatism,” we can get a glimpse of its true nature from a passage in the unfinished English History, a writing project which Burke undertook when he was about 28. Compared with Burke’s other writings this work receives little attention from scholars, and indeed much of it may be seen as less important than his more directly political or philosophical writing. Still, aspects of it yield vital insights into Burke’s thought, and into central questions about knowledge, morality, and politics. Especially noteworthy is Burke’s recounting of the conversion of England to Christianity. In this animated passage he relates the story of how Pope Gregory took care to accomplish the conversion in as gradual a manner as possible.[1] Rather than destroying pagan temples, they were slowly converted to Christian practice; longstanding pagan practices, such as the slaughtering of oxen, were deliberately continued near the new churches. Ceremonies and even doctrines were changed gradually. Burke explains:

Whatever popular customs of heathenism were found to be absolutely not incompatible with Christianity, were retained; and some of them were continued to a very late period. Deer were at a certain season brought into St. Paul’s church in London, and laid on the altar; and this custom subsisted until the Reformation. The names of some of the church festivals were, with a similar design, taken from those of the heathen, which had been celebrated at the same time of the year.[2]

Burke clearly approves of the manner in which the religious conversion was accomplished; he goes so far as to state that the Pope’s policy revealed a “perfect understanding of human nature.” If anything Burke may actually overstate the seamlessness of the transition to Christianity and the melding of the Christian and the pagan; this subject clearly captures his imagination. Why should this be so? For one thing, the incremental change involved in the conversion would seem to fit in well with the usual idea of “Burkean conservatism.” But a problem exists in that “Burkean conservatism” is typically associated with the belief that traditional knowledge and practices are, as a general rule, superior to new schemes. It is certainly not the case here that Burke could believe that the old paganism was superior, or even equal to, Christianity. His belief in and support for Christianity is evidenced throughout his works. While a few commentators have questioned the sincerity of Burke’s religious convictions, the vast majority have not; J. G. A. Pocock for example maintains that “the point at which his thought comes closest to breaking with the Whig tradition to which he deeply belonged was that at which he articulated his concern for clerisy. Burke’s religiosity—his awareness of the sacred, of the need for transcendent moral sanctions—was real.”[3] Moreover, just a few paragraphs earlier in his discussion of the conversion of England Burke remarks that Christianity confers “inestimable benefits on mankind” and that it helped change the “rude and fierce manners” of the Anglo-Saxons.[4]

Of course, one may construct an argument that belief in the superiority of Christianity to paganism is not inconsistent with Burke’s approval of the gradualness of the transition. Such gradualism appears to be a key component of “Burkean conservatism.” Because of the limitations of human reason, we cannot be sure how new schemes will play out; therefore, change should be incremental. However, a problem exists with this model as well. The standard “limitations of human reason” argument is generally used to oppose the sudden adoption of new, untested “rationalistic” schemes. That is, the model is generally understood to argue for respect for tradition, and for caution regarding the implementation of new plans or ideas for society. Christianity, however, was no new scheme; it was, in fact, a tradition, with centuries of experience behind it by the time of its introduction into England. It had been time-tested and, to a degree, had evolved and developed over time. Since Christianity had already been long proven and was not some new idea which had just been cooked up by armchair philosophers, there would presumably be no reason why it should be introduced into England in a cautious, incremental manner. Why then should Burke take a conservative or gradualist position regarding the introduction of Christianity, and even approve of the admixture of presumably inferior pagan elements?

Fortunately, Burke states quite plainly why it was desirable to ensure a gradual transition and to retain aspects of paganism wherever practical. Abrupt changes were avoided “in order that the prejudices of the people might not be too rudely shocked by a declared profanation of what they had so long held sacred.”[5] The danger Burke perceived lay not in Christianity itself as an untested scheme, but in the possible effects of any attempt to disrupt the pagans’ existing worldview. The “prejudices” of the people had grown up over a long period of time in the context of belief in a particular cosmological order and in the context of specific practices related to that belief. Consequently, the sudden profanation of the sacred would have wreaked havoc on the community by undermining its basis for order and meaning. Pope Gregory, in Burke’s eyes, understood the importance of preserving the old framework, and took pains to minimize the disruption which would occur as a result of the change in belief system. This argument, it should be made clear, is quite different from the usual understanding of “Burkean conservatism.” Burke’s focus is not on the “objective” problem of whether or not the innovation is “good,” or whether the change is suitable for the circumstances at hand. His focus is on the subjective experience of the people. This emphasis on subjectivity is one key to Burke’s approach to fundamental problems of order, meaning, and the good.

What informs Burke’s discussion of the conversion of England informs his politics and writings in general. This is a concern for what contemporary writers such as Charles Taylor have referred to in other contexts as “horizons of significance.”[6] Taylor’s term, however, might be understood as referencing explicit religious, moral, or teleological beliefs only, and Burke has much more than this in mind. In the above discussion Burke’s concern is not limited to the gods in which the pagans believed and any explicit moral codes which may have been directly associated with that belief. He is concerned about the rites, the practices, the physical structures, the geographical locations, the calendar, and various other elements which were present in the pagan religious culture. All of these elements worked together to give the pagans a sense of the sacred and to form a framework of order and meaning which shaped their lives. Without this framework the ordered lives and society of the pagans would presumably collapse.

The retention of so much paganism, which Burke regards so positively, might make some Christians uncomfortable. Objections could be raised that it would compromise, corrupt, or, at least, needlessly encumber Christianity. If Christianity’s truth and benefits are acknowledged, then, one might argue, it must follow that only the “purest” form of it should be pursued. Burke, however, sees things differently. For him the approach to the true and the good is not simply intellectual in character but broadly experiential, and involves much more than a conscious rational assent to certain propositions. This favoring of the experiential over the “rational” should not be taken to suggest that Burke is a radical skeptic, that he rejects reason or universals, or that he is less than fully committed to the true and the good. This subject will be taken up in some detail later, when it will be argued that Burke in fact possesses a greater sense of the sacred and a deeper appreciation of the search for what is true and good than do many of his critics.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative