The Salisbury Review, Winter 2012, has just been published

You can see the contents here. More information about The Salisbury Review here.

And you can subscribe this incredible and much valuable Journal here. This could be a very good way of beginning 2013.

Anno Mille, la paura che non fu, by Marco Respinti

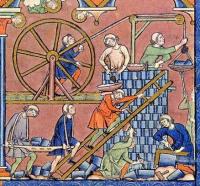

La fine del mondo non è adesso, lo abbiamo visto. I cristiani, come insegnava Gesù, non si preoccupano dell’ora e del giorno, ma preparano costantemente lo spirito per il momento della risurrezione, vivendo sempre operosamente la vita come un tempo ultimo, cioè definitivo e decisivo. Ma il contrario esatto di ciò insegna invece la cultura moderna a partire almeno dall’illuminismo, ovvero quell’epoca di disgregazione sistematica del senso della verità delle cose che ha preteso di riscrivere daccapo e a propria immagine e somiglianza la storia dell’uomo, inventandosi per esempio categorie funzionali come quella di “Medioevo”.

Dall’illuminismo in poi, il “Medioevo” è servito come capro espiatorio di ogni nefandezza o sciocchezza allo scopo di distrarre l’attenzione dai veri responsabili, cioè quelle molteplici “scuole del sospetto” (le ideologie, i relativismi, i nichilismi) che in questo modo hanno potuto proliferare e fare scempi. Uno dei cavalli di battaglia di questa falsificazione della realtà è il presunto oscurantismo generato dallo spirito della religione che la Chiesa Cattolica avrebbe appositamente alimentato per dominare gli uomini e che i vari poteri politici avrebbero volentieri favorito sperando in un condominio. Dunque i “medioevali” – dice la falsificazione illuminista – credevano a tutte le scempiaggini che preti e frati s’inventavano per tenerseli buoni; per esempio alla fine tutte le cose prodotta dalla venuta dell’Anticristo nell’anno Mille.

Sta del resto scritto ne l’Apocalisse che, dopo mille anni di cattività alla catena dell’arcangelo san Michele, Satana sarebbe stato liberato per spadroneggiare finché Cristo, tornando per la seconda e definitiva volta, non avrebbe posto fine ai suoi disastri e stabilito la giustizia per sempre: «Vidi poi un angelo che scendeva dal cielo con la chiave dell’Abisso e una gran catena in mano. Afferrò il dragone, il serpente antico – cioè il diavolo, satana – e lo incatenò per mille anni; lo gettò nell’Abisso, ve lo rinchiuse e ne sigillò la porta sopra di lui, perché non seducesse più le nazioni, fino al compimento dei mille anni. Dopo questi dovrà essere sciolto per un po’ di tempo» (Ap 20, 1-3).

Ora, che i “medioevali” abbiano vissuto atterriti gli ultimi anni prima del Mille lo sappiamo tutti. Lo sappiamo tutti perché di questi e di altri oscurantismi dell’“età buia di mezzo” tutti abbiamo letto. Dove? Difficile ricordarsene. Certamente comunque non in libri di storia fatti come tale disciplina comanda. Perché in realtà le paure dell’anno Mille nei testi veri non ci sono. È solo una colossale montatura.

Parte di questo falso mito potrebbe peraltro basarsi su quel mai sopito, e in realtà solo rimandato, senso della fine imminente che pervadeva i primissimi cristiani, alcuni persino testimoni diretti della predicazione di Gesù. Per loro, il ritorno di Cristo poteva, legittimamente, sembrare cosa imminente; ma poi i Padri della Chiesa, abili sistematori di ottima dottrina, dissiparono il campo dalle illazioni e dalle facili suggestioni – pur ritenute vere da certuni in buona, ottima fede –, ricordando che lo stesso Gesù definisce vano il voler interrogare le stelle circa l’ora e il giorno della fine, nonché peccato l’insistervi.

Si dice che la fantomatica paura “medioevale” dell’anno Mille sarebbe stata salmodiata dalle labbra di sin troppo facili profeti, nella formula «mille e non più mille», che sarebbe un “detto di Gesù”. Ma Gesù non lo ha mai detto. E così nel Mille non accadde proprio alcunché, nessuno si spaventò sul serio e la falsificazione della storia ha dovuto essere riscritta una volta in più, rimandando la data al “più mille”. Il “Medioevo”, ancora, non c’entra affatto.

Che quella delle paure della fine del mondo “tipiche” nell’anno Mille sia in realtà solo una falsa leggenda costruita assai più tardi, cioè nei rinascimentali Annali detti di Hirsau (1511-1513), e questo precipuamente per gettare disprezzo sull’Alto “Medioevo”, venendo in seguito rilanciata in grande stile dal Romanticismo ottocentesco, lo illustra con rigore uno specialista del calibro dello storico francese Georges Duby in un paio di bei libri, quali L’Anno Mille. Storia religiosa e psicologia collettiva (trad. it. Einaudi, Torino 2001) e Mille e non più Mille. Viaggio tra le paure di fine millennio (con Chiara Frugoni, trad. it., Rizzoli, Milano 1999). Un solo scritto “medioevale” parla infatti di eventi strabilianti e inquietanti avvenuti nel Mille, il Chronicon (o Chronographia) del monaco benedettino Sigebert di Gembloux, che descrive il periodo tra il 381 e il 1111: ma è un testo del secolo XII. Parecchio successivo al Mille. Al massimo, cioè, Sigebert riporta, riferisce, copia notizie di altri. Il forte sisma del Mille di cui parla nel suo Chronicon quel buon monaco lo trae per esempio dagli Annales Leodienses, ma le fonti delle sue altre “notizie”? E per di più Sigebert tace completamente dei presunti terrori che si sarebbero diffusi nella popolazione cristiana del “Medioevo” all’avvicinarsi del Mille. Per trovarne le prime tracce occorre appunto attendere il secolo XVI.

Read the complete article in La nuova bussola quotidiana

Ten Conservative Books Revisited, by Gerald J. Russello

In 1986, Russell Kirk gave a lecture titled “Ten Conservative Books” in which he identified ten important books that distilled or expressed conservative principles, from Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France to T. S. Eliot’s Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, the book Kirk pressed upon the hapless Richard Nixon. The essay is worth reading not only for the book suggestions but also for what Kirk has to say about the role of books in the culture; as a bookish person himself, Kirk valued tomes highly, and having been in his library—a converted factory near his ancestral Piety Hill home—there is no question that Kirk was a bibliophile.

Yet Kirk recognized that “It is possible for books to comment upon custom, convention, and continuity; but not for books to create those social and cultural essences. Society brings forth books; books do not bring forth society.” Cultural renewal must occur at the level of the person, family, and community; books can help that process, but wise books come from societies that value and reflect upon wisdom; rarely the other way round.

With that in mind, there is some merit in supplementing Kirk’s list a quarter century on, so herewith my choices for ten conservative books.

1. Joseph Roth, The Radetzky March. In his list, Kirk abjured fiction, although in passing he recommended some authors such as Robert Louis Stevenson and Nathaniel Hawthorne. The Radetzky March covers the period leading up to the dissolution of the old European Order before, and as a result of, World War I. Like Giuseppe Lampedusa’s The Leopard, Roth is clear-eyed about the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its many flaws, but equally clear-eyed about what he calls the “bestial” promise of an order that had ripped aside its traditions.

2. Patrick Leigh-Fermor, A Time for Gifts. Leigh-Fermor, who died recently, was in some sense the highest product of the tradition whose destruction Roth lamented. A polymath, courageous soldier (he led a British commando unit in occupied Crete during World War II), and elegant writer, Leigh-Fermor as a young man walked through Europe to Constantinople, just as Nazism was rising on the Continent. This book, the first volume of two covering the journey, describes a pre-Internet, pre-EU Europe of deeply local customs and perspectives, a collage of nations that is almost impossible for us to imagine; almost, because Leigh-Fermor’s prose makes such imagination possible.

3. Christopher Dawson, Religion and the Rise of Western Culture. The Europe Roth and Leigh-Fermor describe was a disparate set of people bound together by a common faith. How that faith—which itself came from outside Europe, bearing with it the markings of Israel and the Near East—came to shape Europe is described in this book, written by one of the twentieth century’s greatest Christian historians.

4. John Lukacs, Last Rites. After Dawson Lukacs is perhaps the historian every conservative should read. Lukacs—a Hungarian refugee to the United States—has written a series of books articulating a defense of European and specifically Anglo-American civilization. He is no mindless defender of right-wing orthodoxy—far from it. But his perspective on patriotism and the moral nature of history, among many other subjects, makes this book—a follow up to his amazing first volume of memoirs, Confessions of an Original Sinner—a perfect introduction to his other works, including the indispensable Historical Consciousness, which explodes every progressive myth about historical thinking you can imagine.

5. Russell Kirk, The Conservative Mind. Although Kirk did not include his own works in his listing, now, some five decades on, his masterpiece, The Conservative Mind, needs to be read by anyone seeking to understand the conservative tradition. As David Frum once wrote, Kirk as much created as discovered the conservative intellectual tradition, which he traced from Edmund Burke to Eliot. And it is that tension between preservation and innovation that lay at the heart of Kirk’s project, a tension that Kirk navigated through reverence for the past but also the consistent application of imagination to the problems of the present

Read the complete article in The University Bookman