Roger Scruton, filósofo inglés sin tapujos: «¿La ley sobre la homofobia? Como los procesos de Mao», by Giulio Meotti

George Orwell ya dijo todo en sus famosos ‘dos minutos de odio’ de la novela ‘1984’”, dice al Foglio (www.ilfoglio.it) el filósofo y comentarista inglés Roger Scruton (www.roger-scruton.com).

“La cuestión homosexual es complicada y difícil, pero no puede encarcelar el pensamiento con leyes sobre la denominada ‘homofobia’ como la del Parlamento italiano, que lo único que hace es criminalizar la crítica intelectual sobre el matrimonio homosexual. Es un nuevo crimen intelectual, ideológico, como fue el anticomunismo durante la Guerra Fría”.

Docente de Filosofía en la St. Andrews University, setenta años, autor de una treintena de libros que le han convertido en el más célebre filósofo conservador inglés (ha sido definido por el Sunday Times “the brightest intellect of our time”, “la mente más brillante de nuestro tiempo”), Scruton comenta de este modo la ley que se está debatiendo en el Parlamento italiano sobre la criminalización de la “homofobia”. También Amnistía Internacional se está movilizando en apoyo de esta ley.

Como los juicios-farsa y el maoísmo

“Esta ley sobre la homofobia me recuerda a los juicios farsa-espectáculos de Moscú y de la China maoísta, en los que las victimas confesaban con entusiasmo sus propios crímenes antes de ser ajusticiados. En todas estas causas en las que los optimistas acusan a los opositores de ‘odio’ y ‘discurso del odio’ veo lo que el filósofo Michael Polanyi definió, en 1963, como ‘inversión moral’: si desapruebas el welfare (el bienestar social) te falta ‘compasión’; si te opones a la normalización de la homosexualidad eres un ‘homófobo’; si crees en la cultura occidental eres un ‘elitista’. La acusación de ‘homofobia’ significa el final de la carrera, sobre todo para quien trabaja en la universidad”.

Distorsionan el lenguage: vuelve Orwell

Scruton sostiene que la manipulación de la verdad pasa a través de la distorsión del lenguaje, como en la obra de Orwell, con el nombre de “Neolengua”.

“La neolengua interviene cada vez que el propósito principal de la lengua, que es describir la realidad, es sustituido por el propósito opuesto: la afirmación del poder sobre ella. Aquí, el acto lingüístico fundamental coincide sólo superficialmente con la gramática asertiva. Las frases de la neolengua suenan como aserciones en las cuales la única lógica subyacente es la de la fórmula mágica: muestran el triunfo de las palabras sobre las cosas, la futilidad de la argumentación racional y el peligro de resistir al encantamiento. Como consecuencia, la neolengua desarrolla una sintaxis especial que, si bien está estrechamente conectada a la que se utiliza normalmente en las descripciones ordinarias, evita con cuidado rozar la realidad o confrontarse con la lógica de la argumentación racional. Es lo que Françoise Thom ha intentado ilustrar en su estudio, ‘La langue de bois’ (“La lengua de madera”). Thom ha puesto de relieve algunas de sus peculiaridades sintácticas: el uso de sustantivos en lugar de verbos directos; la presencia de la forma pasiva y de la construcción impersonal; el uso de comparativos en lugar de predicados; la omnipresencia del modo imperativo”.

La “homofobia”, un fantasma

Con la ley sobre la homofobia, Scruton dice que “se intenta infundir en la mente del público la idea de una fuerza maligna que invade toda Europa, albergándola en los corazones y en la cabeza de la gente que ignora sus maquinaciones, y dirigiendo hacia el sendero del pecado incluso el proyecto más inocente. La neolengua niega la realidad y la endurece, transformándola en algo ajeno y resistente, algo ‘contra lo que luchar’ y a lo que ‘hay que vencer’. El lenguaje común da calor y ablanda; le neolengua congela y endurece. El discurso común genera, con sus mismos recursos, los conceptos que la neolengua prohíbe: correcto-incorrecto; justo-injusto; honesto-deshonesto; tuyo-mío”.

Una forma de “reeducación”

Scruton dice que se está expandiendo en los países europeos el miedo a la herejía. “Está emergiendo un sistema considerable de etiquetas semioficiales para prevenir la expresión de puntos de vista ‘peligrosos’. La amenaza se difunde de manera tan rápida en la sociedad que no es posible evitarla. Cuando las palabras se convierten en hechos, y los pensamientos son juzgados por la expresión, una especie de prudencia universal invade la vida intelectual”.

Y detalla más lo que pasa cuando se habla con miedo: “La gente modera el lenguaje, sacrifica el estilo a una sintaxis más ‘inclusiva’, evita sexo, raza, género, religión. Cualquier frase o idioma que contenga un juicio sobre otra categoría o clase de personas puede convertirse, de la noche a la mañana, en objeto de estigmatización. Lo políticamente correcto es una censura blanda que permite mandar a la gente a la hoguera por pensamientos ‘prohibidos’. Las personas que tienen un ‘juicio’ son condenadas con la misma violencia de Salem”. El del juicio a las brujas, en Massachusetts [1]. La letra escarlata [2].

Quien disienta del lobby gay será “homófobo”

“Quien se angustie por todo esto y quiera expresar su protesta deberá luchar contra poderosas formas de censura. Quien disienta de lo que se está convirtiendo en ortodoxia en lo que respecta a los ‘derechos de los homosexuales’ es regularmente acusado de ‘homofobia’. En Estados Unidos hay comités encargados de examinar el nombramiento de los candidatos en el caso de que exista la sospecha de ‘homofobia’, liquidándolos una vez que se ha formulado la acusación: ‘No se puede aceptar la petición de esa mujer de formar parte de un jurado en un juicio, es una cristiana fundamentalista y homofóbica’”.

Según Scruton, se trata de una operación ideológica que recuerda, exactamente, la que tuvo lugar durante la Guerra Fría.

“Entonces se necesitaban definiciones que estigmatizaran al enemigo de la nación para justificar su expulsión: era un revisionista, un desviacionista, un izquierdista inmaduro, un socialista utopista, un social-fascista. El éxito de estas ‘etiquetas’ marginando y condenando al opositor corroboró la convicción comunista de que se puede cambiar la realidad cambiando el lenguaje: por ejemplo, se puede inventar una cultura proletaria con la palabra ‘proletkult’; se puede desencadenar la caída de la libre economía simplemente declarando en voz alta la ‘crisis del capitalismo’ cada vez que el tema es debatido; se puede combinar el poder absoluto del Partido Comunista con el libre consentimiento de la gente definiendo al gobierno comunista como un ‘centralismo democrático’. ¡Qué fácil ha sido asesinar a millones de inocentes visto que no estaba sucediendo nada grave, pues se trataba solamente de la ‘liquidación de los kulaki’ [3]! ¡Qué fácil es encerrar a la gente durante años en campos de trabajo forzado hasta que enferma o muere, si la única definición lingüística concedida es ‘reeducación’!. Ahora existe una nueva beatería laica que quiere criminalizar la libertad de expresión sobre el gran tema de la homosexualidad”.

Dicen “nosotros”… y son solo los progres

Por último, dice Scruton, tenemos el choque entre el “pragmatista” y el “racionalista”.

“Las viejas ideas de objetividad y verdad universal ya no tienen ninguna utilidad, lo único importante es que ‘nosotros’ estemos de acuerdo. Pero, ¿quién es este ‘nosotros’?¿Y sobre qué estamos de acuerdo? ‘Nosotros’ estamos todos a favor del feminismo, somos todos liberales, defensores del movimiento de liberación de los homosexuales y del currículum abierto; ‘nosotros’ no creemos en Dios o en cualquier otra religión revelada, y las viejas ideas de autoridad, orden y autodisciplina para nosotros no cuentan”.

Y continúa: “Nosotros decidimos el significado de los textos, creando con nuestras palabras el consentimiento que nos gusta. No tenemos ningún vínculo, sólo el que nos une a la comunidad de la que hemos decidido formar parte, y puesto que no existe una verdad objetiva, sino sólo un consentimiento autogenerado, nuestra posición es inatacable desde cualquier punto de vista fuera de ella. El pragmatista no sólo puede decidir qué pensar, sino que también se puede proteger contra cualquiera que no piense como él”.

—

[1] El autor hace referencia a los juicios por brujería de Salem, en Massachusetts (EE.UU.), una serie de audiencias locales, posteriormente seguidas por procesos judiciales formales, llevados a cabo por las autoridades con el objetivo de procesar y después, en caso de culpabilidad, castigar delitos de brujería en los condados de Essex, Suffolk y Middlesex, entre febrero de 1692 y mayo de 1693. Este acontecimiento se usa de forma retórica en la política como una advertencia real sobre los peligros de la intromisión gubernamental en las libertades individuales, en el caso de acusaciones falsas, de fallos en un proceso o de extremismo religioso. (N.d. T.)

[2] El autor hace referencia a la novela de Nathaniel Hawthorne, “La letra escarlata”, publicada en 1850. Ambientada en la puritana Nueva Inglaterra de principios del siglo XVII, relata la historia de Hester Prynne, una mujer acusada de adulterio y condenada a llevar en su pecho una letra “A”, de adúltera, que la marque.

[3] La “liquidación de los kulaks como una clase social”, o deskulakización, fue anunciada oficialmente por Iósif Stalin el 27 de diciembre de 1929. Fue la campaña soviética de represión política contra los campesinos más ricos o kulaks y sus familias; entre arrestos, deportaciones y ejecuciones, afectó de manera muy grave a millones de personas en el período 1929-1932.

(Traducción de Helena Faccia Serrano)

Publicado en Religión en Libertad

Overpopulation: Mother of all myths, by Jeb Blackwood

The world’s population is declining.

Those are fighting words in most circles but it’s the truth, and it’s occurring right before our eyes.

How can that be when in 2012 the US Census Bureau estimated the world population at 7 billion? That’s a lot of zeros! Well, the proof is in the statistics.

Let’s begin with what we know about fertility rate. To achieve perfect replacement, humans must have 2.13 children per woman. Some women have more children while others have fewer, but 2.13 is the magic number to maintain steady population. More than 90 countries (the USA and Canada among them) are currently experiencing a birthrate under that magic number . People are simply not having children.

And when we look at the 2009 United Nations documentation, “World Population Prospects” (yes, THE United Nations), the outlook appears grim. Not only do all six countries included on the chart show a marked birthrate decline over the last 60 years, but they all drop below the sustainability rate of 2.13 children per woman.

Pay close attention to the countries on the chart: the United States, Japan, Germany, France, Italy and Britain. All are world powers, and provide economic stability in their regions and to the world. So what if people stop having children? What difference does it make? There is a strong correlation between economic downturn and declining fertility rates.

read the complete article in Intercollegiate Review

The Road to Same-Sex Marriage was Paved by Rousseau, by Robert R. Reilly

At the heart of the debate over same-sex marriage are fundamental questions about who men are and how we decide what makes us flourish.

Ineluctably, the issue of “gay” rights is about far more than sexual practices. It is, as lesbian advocate Paula Ettelbrick proclaimed, about “transforming the very fabric of society … [and] radically reordering society’s views of reality”.

Since how we perceive reality is at stake in this struggle, the question inevitably rises: what is the nature of this reality? Is it good for us as human beings? Is it according to our Nature? Each side in the debate claims that what they are defending or advancing is according to Nature.

Opponents of same-sex marriage say that it is against Nature; proponents say that it is natural and that, therefore, they have a “right” to it. Yet the realities to which each side points are not just different but opposed: each negates the other. What does the word Nature really mean in this context? The words may be the same, but their meanings are directly contradictory, depending on the context. Therefore, it is vitally important to understand the broader contexts in which they are used and the larger views of reality of which they are a part since the status and meaning of Nature will be decisive in the outcome.

Let us then review briefly what the natural law understanding of “Nature” is and the kinds of distinctions an objective view of reality enables us to make in regard to our existence in general and to sexuality in particular. The point of departure must be that Nature is what is, regardless of what anyone desires or abhors. We are part of it and subject to it. It is not subject to us. Thus, we shall see how, once the objective status of Nature is lost or denied, we are incapacitated from possessing any true knowledge about ourselves and about how we are to relate to the world. This discussion may seem at times somewhat unrelated to the issues directly at hand, but it is not. It is at its heart and soul. Without it, the rest of our discussion is a mere battle of opinions.

Order in the Universe – Aristotle’s Laws of Nature

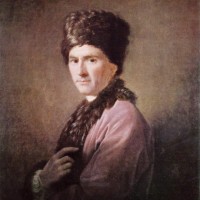

There are two basic, profoundly different anthropologies behind the competing visions of man at the heart of the dispute over same-sex marriage. For an understanding of the original notion of Nature, we will turn to those who began the use of the term in classical Greece, most especially Plato and Aristotle. To present the antithesis of this understanding, we will then turn to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who eviscerated the word of its traditional meaning in the 18th century and gave it its modern connotation.

The older anthropology is Aristotelian, which claims that man is by Nature a political animal for whom the basic societal unit is the family. The newer is Rousseauian, which claims that man is not a political animal and that society in any form is fundamentally alien to him. These two disparate anthropologies presuppose, in turn, two radically different metaphysics: one is teleological; the other is non-teleological, or anti-teleological. Again, the first one has its roots in Aristotle, the second in Rousseau. These two schools of thought provide convenient and necessary philosophical perspectives within which to understand the uses of the words “natural” and “unnatural” as they are variously employed by the proponents and opponents of homosexual acts and same-sex marriage today.

The discovery of Nature was momentous, as it was the first product of philosophy. Man first deduced the existence of Nature by observing order in the universe. The regularity with which things happen could not be explained by random repetition. All activity seems governed by a purpose, by ends to which things are designed to move. Before this discovery, in the ancient, pre-philosophical world, man was immersed in mythological portrayals of the world, the gods, and himself. These mythopoeic accounts made no distinction between man and Nature, or between convention and Nature. A dog wagged its tail because that was the way of a dog. Egyptians painted their funeral caskets in bright colors because that was the way of the Egyptians. There was no way to differentiate between the two because the word “Nature” was not available in the vocabulary of the pre-philosophical world.

According to Henri Frankfort in Before Philosophy, it was Heraclitus who first grasped that the universe is an intelligible whole and that therefore man is able to comprehend its order. If this is true – and only if it is true – man’s inquiry into the nature of reality becomes possible. The very idea of “Nature” becomes possible. How could this be? Heraclitus said that the universe is intelligible because it is ruled by and is the product of “thought” or wisdom. If it is the product of thought, then it can be apprehended by thinking. We can know what is because it was made by logos. We can have thoughts about things that are themselves the product of thought.

As far as we know, Heraclitus and Parmenides were the first to use the word logos to name this “thought” or wisdom. Logos, of course, means “reason” or “word” in Greek. Logos is the intelligence behind the intelligible whole. It is logos which makes the world intelligible to the endeavor of philosophy, ie, reason. In the Timaeus, Plato writes, “… now the sight of day and night, and the months and the revolutions of the years, have created number, and have given us a conception of time; and the power of inquiring about the nature of the universe; and from this source, we have derived philosophy, than which no greater good ever was or will be given by the gods to mortal man.” Through reason, said Socrates, man can come to know “what is”, ie, the nature of things.

Aristotle taught that the essence or nature of a thing is what makes it what it is, and why it is not something else. This is not a tautology. As an acorn develops into an oak tree, there is no point along its trajectory of growth that it will turn into a giraffe or something other than an oak. That is because it has the nature of an oak tree. By natural law, in terms of living things, we mean the principle of development which makes it what it is and, given the proper conditions, what it will become when it fulfills itself or reaches its end. For Aristotle, “Nature ever seeks an end”. This end state is its telos, its purpose or the reason for which it is. In non-human creation this design is manifested through either instinct or physical law. Every living thing has a telos toward which it purposefully moves. In plants or animals, this involves no self-conscious volition. In man, it does.

Anything that operates contrary to this principle in a thing is unnatural to it. By unnatural, we mean something that works against what a thing would become were it to operate according to its principle of development. For instance, an acorn will grow into an oak unless its roots are poisoned by highly acidic water. One would say that the acidic water is unnatural to the oak or against its “goodness”.

The term “teleological”, when applied to the universe, implies that everything has a purpose, and the purpose inheres in the structure of things themselves. There is what Aristotle called entelechy, “having one’s end within”. The goal of the thing is intrinsic to it. These laws of Nature, then, are not an imposition of order from without by a commander-in-chief, but an expression of it from within the very essence of things, which have their own integrity. This also means that the world is comprehensible because it operates on a rational basis.

It is by their natures that we are able to know what things are. Otherwise, we would only know specificities, and be unable to recognize things in their genus and species. In other words, we would only experience this piece of wood (a tree), as opposed to that piece of wood (another tree), but we would not know the word “tree” or even the word “wood”, because we would not know the essence of either. In fact, we would know nothing.

Nature is also what enables one person to recognize another person as a human being. What does human nature mean? It means that human beings are fundamentally the same in their very essence, which is immutable and, most profoundly, that every person’s soul is ordered to the same transcendent good or end. (This act of recognition is the basis of Western civilization. We have forever since called barbarian those who are either incapable of seeing another person as a human being or who refuse to do so.) Both Socrates and Aristotle said that men’s souls are ordered to the same good and that, therefore, there is a single standard of justice which transcends the political standards of the city. There should not be one standard of justice for Athenians and another for Spartans. There is only one justice and this justice is above the political order. It is the same at all times, everywhere, for everyone.

For the first time, reason becomes the arbiter. Reason becomes normative. It is through reason – not from the gods of the city – that man can discern what is just from what is unjust, what is good from what is evil, what is myth from what is reality. Behaving reasonably or doing what accords with reason becomes the standard of moral behavior. We see one of the highest expressions of this understanding in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

As classics scholar Bruce S. Thornton expressed it: “If one believes, as did many Greek philosophers from Heraclitus on, that that the cosmos reflects some sort of rational order, then ‘natural’ would denote behavior consistent with that order. One could then act ‘unnaturally’ by indulging in behavior that subverted that order and its purpose”. Behaving according to Nature, therefore means acting rationally. Concomitantly, behaving unnaturally means acting irrationally. This notion of reality necessitates the rule of reason.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative