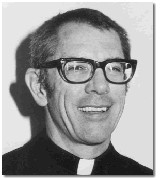

On the Reading of Books, by Rev. James V. Schall, S.J

On Thursday, May 1, 1783, with “the young Mr. (Edmund) Burke” present, Samuel Johnson remarked: “It is strange that there should be so little reading in the world and so much writing. People in general do not willingly read if they can have anything else to amuse them.” The word “reading” here does not mean, say, the reading of e-mails, which are read immediately on reception. Rather, “reading” here means setting aside time and giving attention. Reading is an actively passive occupation. I never read without a pencil, except perhaps when reading my breviary (but this is only because, if I had a pencil over lo these many years, the whole four volumes would be underlined).

The subject of the pleasure of books was recently brought to my attention by the unexpected gift of a used book, Christopher Morley’s 1919 classic The Haunted Bookshop, a book I had never heard of before. Mr. Mifflin, the proprietor of the Haunted Bookshop, when asked by a young man whether a used book shop is not “delightfully tranquil,” replied, “Far from it. Living in a bookshop is a little like living in a warehouse of explosives. Those shelves are ranked with the most furious combustibles in the world — the brains of men.”

So it was sobering to read Johnson, who added: “No man reads a book of science from pure inclination. The books that we do read with pleasure are light compositions, which contain a quick succession of events.” Johnson then went on to admit, however, that he had recently read the complete works of Virgil with great pleasure.

So the question of reading must include, “The reading of what?” And I suppose a distinction can be found between reading for pleasure and the pleasure of reading. I can well imagine reading a scientific book with pleasure, coming across the explanation of something that had long puzzled us, now spelled out in coherent and clear form.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

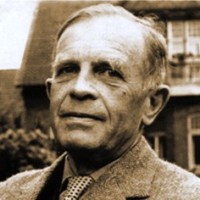

Wilhelm Roepke: German Economist as Southern Neighbor, by Ralph E. Ancil

How can a German economist be called a Southerner? Obviously not geographically but in the important sense that Southern Agrarians came to understand, as a possession of the mind and spirit. That Wilhelm Roepke’s mind and spirit, embodying the best of the German tradition, share significantly in the essential features of the Southern heritage is not too surprising when it is recalled that Southern culture itself was essentially European.

In evidence of this there are some suggestive comparisons that can be made here. For example, Richard Weaver went home in spring to farm his ancestral fields with horse and plow and refused the use of airplanes, preferring trains for long distance travel. Similarly, Roepke promoted urban gardening for the health of city-dwellers and refused to use ski-lifts, preferring to ride up the mountain slopes on shank’s mare. Or one may refer to the Southern fondness for the books of Sir Walter Scott whose stories of Saxon yeomen fighting Norman invaders parallels those of William Tell fighting Austrian conquerors as eulogized in Schiller’s famous poem, admired by Roepke. Then one may conjecture about the influence of Germans and Lutherans on Southern life. Certainly, Luther himself was a social medievalist and agrarian and longed for the non-commercial life of an earlier time. To what extent this affected Southern life is arguable as is the effect of his Lutheran faith on Roepke’s outlook. But the parallels are thought-provoking.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Russell Kirk Defends Assassination with Natural Law Theory, by Bradley J. Birzer

Therefore a little knot of brave and conscientious men determined to save Germany and Europe by killing Hitler…

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

Conservative Credo, by Barbara J. Elliott

Conservatism seeks the Truth that has emerged over time, drawing from the deep wellsprings of human experience, and builds anew on foundations that have withstood the tests of time. It fosters order and the flourishing of human beings as they live in relationship with one another. We are united in the eternal contract between the dead, the living, and the yet unborn.

Conservatism is rooted in the acknowledgement that God is our Creator and that the human soul sojourns through this realm toward its eternal transcendent fulfillment. We are all flawed human beings in need of redemption, capable of great evil as well as great good.

Because man is fallible by nature, the conservative seeks to limit the damage that can be done through the abuse of power by limiting its concentration.

The conservative fosters the fullness of human potential by protecting the freedom and dignity of each individual, acknowledging that responsibility comes with freedom. Rights and duties are always linked.

For the conservative, each man and woman is equal in dignity and equal before the law, but gloriously individual and unequal in talents, aptitudes, and outcomes. The conservative celebrates the uniqueness of individuals and does not level to eliminate differences.

The conservative honors the family as the essential building block of civilization, the house of worship as the locus for forming culture, and the community as the matrix for human interaction. Culture and community grow from relationships and affinities over time, rooted in place. Conservatives value the rich diversity of relationships, organizations, and private associations that make up civil society and intermediary institutions.

The conservative values subsidiarity because we know many of the best solutions to human problems are found at the level closest to the individual person. We foster personal, local care for persons in need, preferably face-to-face with someone whose name we know. We believe that human transformation occurs best in the context of a personal, loving relationship, with accountability, over time.

The conservative is more concerned with the culture than politics, because the political realm is a derivative one, not primary, in human existence. Political problems are at their root moral and spiritual problems, which blend into the economic realm. Political change is rooted in cultural change.

Conservatives believe that caring for our neighbor is so important that it should not be left to the government. The one thing government cannot do is love. That is what we are called to do in the private sector, with our own time, talent, and treasure.

The conservative believes that that the True, the Good, and the Beautiful are interrelated, and that all things are measured against these three transcendentals.

We believe that there is Truth, that it is knowable, and that it is our duty to seek Truth and live it throughout our lives. The conservative believes that the virtues of Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance should be practiced in both private and public life. We believe that virtues, not values, define the human soul.

We believe that Love is the highest motivation of the human person and that the purpose of life itself is to know God, to love Him and serve Him, and to love our neighbor as ourselves. Our ultimate fulfillment is in the transcendence of love.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative

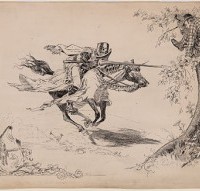

Mark Twain and Russell Kirk against the Machine

Though neither an humanist nor a Christian—nor, for that matter, even a romantic in the vein of Blake who feared the “dark Satanic mills” of Industrial England—Mark Twain identified the late-nineteenth century fear of the machine run amok perfectly in his last novel, the tragically whimsical A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. One of the first to use time travel as a plot device, the story revolves around Hank Morgan, an engineer devoid of any poetry or sentiment. As his German last name indicates, he is the man of “tomorrow.” A practical man schooled in the servile rather than the liberal arts, Morgan can create almost any type of mechanism: “guns, revolvers, cannon, boilers, engines, all sorts of labor-saving machinery.” A materialist, he “could make anything a body wanted—anything in the world, it didn’t make a difference what; and if there wasn’t any quick new-fangled way to make a thing, [he] could invent one.” He was also, Hank assures the reader, “full of fight.” And, a conflict employing crowbars with one of his employees, a man named Hercules, results in severe blow to Morgan’s head, knocking him unconscious.

Read the complete article in The Imaginative Conservative